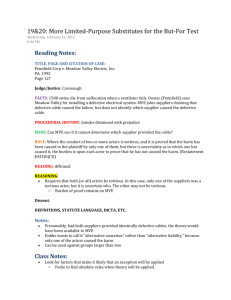

CAUSATION SINCE NASSAR: Some Thoughts By: John Thomas

advertisement

CAUSATION SINCE NASSAR: Some Thoughts By: John Thomas Moran Med. Ctr. v. 570 U.S. , 133 S. Ct. 2517 (U.S. 2013), the burden on retaliation in the Title VII context is but-for causation. That decision was only based upon the specific wording and statutory framework of Title VII and it does not appear to impact § 1981 claims for retaliation as allowed under CBOCS West, Inc. v. Humphries, 553 U.S. 442 (2008) in which the "motivating factor" causation standard (not "but-for" causation) is used. There can be several "but for" causes in any one decision, and several different straws that broke the camel's back. Thus, in Ponce v. Billington, 679 F.3d 840 (2012) the D.C. Circuit last year "banish[ed] the word 'sole' from [its] Title VII lexicon!' One example: "consider an entity undergoing a reduction-in-force that identifies underperforming employees, but selects only the women from among that group for termination. Although there remains a true and a valid reason for the action, the women may state a claim under§ 2000e-2(a) because they would not have been terminated 'but-for' their sex." In that example there are two "but for" causes: performance and gender. but conceivably a dozen or more could be at issue in any one employment decision and if one of them is gender it is illegaL With the Nac'l'Sar decision and its predecessor, Gross v. FBL Financial Services, Inc., 557 U.S. 167 (2009), different causation standards now apply to Title VII retaliation claims and status-based discrimination claims. To survive summary judgment and to prevail at trial, an employee will now have to prove that illegal retaliation by the employer actually caused the harm that is alleged. The alternative and more lenient standard would have permitted an employee to prove liability even if the allegedly illegal conduct were just a motivating factor (not the actual reason) for the adverse employment action. But it is important to note that "but for" causation does not mean "sole cause." The Supreme Court has held that a "but for" causation standard was not the same as a "sole cause" standard in a number of decisions. See McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co., 427 U.S. 273, 282 n. 10, (1976). Hazen Paper, which is relied upon in Gross, does not establish a "sole cause" standard in the ADEA and in fact explicitly references that liability under the ADEA may follow even when there is liability under both the ADEA and ERISA where the employer's decision to fire the employee was motivated by both the employee's age and by his pension status. Hazen Paper Co. v. Biggins, 507 U.S. 604,613 (1993). The response to both Gross and lvfcDonald-Douglas. this: is, in the judgment of some scholars, to reinvigorate at Boston University School Law has noted The courts understand that plaintiffs can prove determinative, "but-for" causation at least as well through the pretext proof system of McDonnell Douglas as through the use of evidence of bad motivation, like the sex stereotyping comments in Price Waterhouse. The McDonnell Douglas pretext proof methodology is especially well suited to proving determinative causation. The utility of this methodology for plaintiffs is that it allows proof of a bad discriminatory motive to rest on the proof of the absence of a credible non-discriminatory motive. Pretext proof allows plaintiffs to prove the presence of the bad by the absence of the good. Thus, contrary to the understanding of many confused students and judges, the distinction between indirect proof of the bad through proof of pretext and direct proof of the bad is not the same as the distinction between direct and circumstantial evidence. As the Supreme Court has repeatedly tried to make clear, the purpose of the McDonald Douglas prima facie case is not to set a standard for avoiding dismissal on the pleadings23 or for summary judgment, nor to set minimum conditions for all proofs of discriminatory intent.2s Rather, by eliminating the most obvious reasons for a challenged personnel decision, proving the prima facie case merely forces a defendant to articulate what it claims are the non-discriminatory reasons for the decision, so that the plaintiff has an opportunity to show those reasons are not credible, and thereby prove the bad by the absence of the good. Once a defendant presents evidence of a legitimate reason, the prima facie case has no remaining function or force.26 Notice that proving the total absence of a good reason for a challenged decision proves not only determinative, "but-for" causation, but also sole causation from the suspected bad reason. And even when pretext proof does not totally eliminate a good reason, it may prove that the good reason was not sufficient in itself, thus raising the inference that the bad reason was necessary, i.e. was a "but-for" cause of the decision. The best and most common proof of pretext is through better treated comparators outside the protected class, or, in the case of the ADEA, substantially younger,21 who share the attributes the employer claimed to rely on to justify its more negative treatment of the plaintiff. Regardless of the nature of pretext proof, however, it is only effective if it demonstrates that the employer's justification was fully fabricated or at least was not sufficient to cause the challenged decision, i.e. that some other reason was also necessary. Logically, one cannot use the inadequacy of good reasons to prove the presence of a bad reason without proving that the bad reason not only existed, but also was a necessary cause of the challenged decision. In most cases employers would want to explain their justifications for a challenged decision even if not forced to do so by the rebuttable, but mandatory presumption set by the prima facie case. Most employers, without being forced by some legal presumption, would want to provide a jury a justification for replacing a qualified older worker with a younger worker. Direct proof of a bad discriminatory reason, whether or not that direct proof is circumstantial for purposes of the law of evidence, can at least contribute to proof of determinative causation by demonstrating the force of the decision maker's bias. zs Plaintiffs should be able to marshal together all their evidence of discriminatory intent and causation, both direct and pretextbased.29 In most cases, it is probably necessary to demonstrate the inadequacy of employer justifications, and not just the existence of discriminatory bias, in order to prove determinative, "but-for" causation. 2 See Swierekiewicz v. -.nrt>mn United States Postal Service Board the nrnnorhJ made out a that would be defendant has done facie case, whether the did so is no relevant. The McDonnell """''UI''., framework could not have been intended as a jury control device because were not available in Title VII actions when that framework was constructed before the 1991 Act. See ·see also Reeves v. Sanderson Inc., 530 U.S. that the defendant's one form of circumstantial evidence that is of Honor center v. 510 the defendant to carry a burden of production); ncc:vc::>. t>mrunv.. r nrt><:t>nt;:>rl evidence of a reason, the McDonnell framework" issue was 'discrimination vel non. sole See O'Connor v. Consolidated Coin Caterers Corp., 517 U.S. 308 (1996). for the Court's analysis of direct evidence of age bias along with pretext evidence in 530 U.S. at 151-153. Finally, the "but for" standard of causation may be a lesson in semantics because one Seventh Circuit opinion predating Nassar, seems to say that "but for" causation is not enough, that the employee must establish the reasons are pretextual. See Casanova v. American Airlines, Inc., 616 F.3d 695 (7th Cir. 2010). Of course, that puts us back in the A1cDonald-Douglas framework which we are all familiar with. In Casanova, the 7th Circuit found that the plaintiff's untruthfulness and insubordination to American Airlines constituted more than adequate grounds for his termination. In Illinois, after an employer provides a valid reason for a plaintiff's termination, the plaintiff must establish that the reason offered by the employer is pretextual. In Casanova, the plaintiff did not provide any evidence to establish that American Airlines' stated reasons for firing him were pretextual. There it was undisputed that the plaintiff lied and refused to obey the airlines' procedures and instructions. 3