Corporate Reorganizations, Job Layoffs, and Age Discrimination

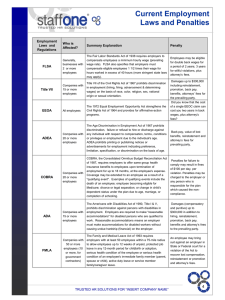

advertisement