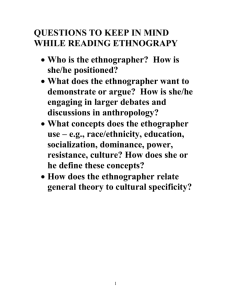

Revisits: An Outline of a Theory of Reflexive Ethnography.

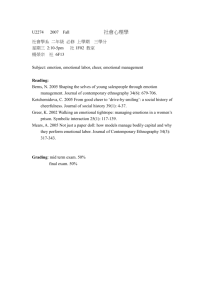

advertisement