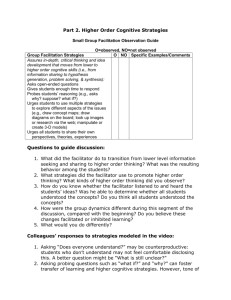

A Manual for Group Facilitators

advertisement