Please click to pdf notes

advertisement

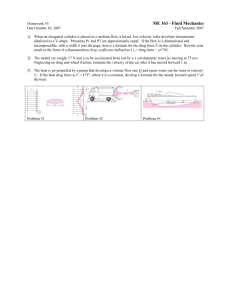

Airfoils in Supersonic Flow Linear theory Recall that for isentropic flow over a corner (Prandtl-Meyer Expansion), we obtained: dp Md M2 1 Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 1 Now we can argue that for small angles of compression, only weak oblique shocks will be formed, and the entropy increase is minimal. In fact, it can be shown that , so that is small for small for weak compressions as well. . Therefore, the relations for isentropic flow should hold Using the expression for dp, we can write, for small changes, or, or Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 2 Sign of cp Note that by definition should be positive when , i.e. the pressure is higher than the freestream static pressure (compression). This is easier to keep in mind than any sign convention for . Lift Coefficient For small , where is the equation to the airfoil surface. Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 3 Lift per unit span, where Note that respect to is pressure on the lower surface and where is pressure on the upper surface. is the distance along the chord and is the slope with . Given the equations to the upper and lower surfaces can find . Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath and we 4 Example 1 Flat plate at angle of attack . Upper surface: Lower surface: ((How do we figure g out whether it should be + or - ? Think about the sign g of cP. The upper surface is an expansion surface -- negative cP while the lower surface is a compression surface … positive cp) Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 5 This is a very useful result. result In fact, fact this is valid for relatively large values of as well. well Note that attack. Cl 2 1 M 1 for an ideal thin airfoil in subsonic flow at small angle of 2 Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 6 Example 2 Airfoil with thickness at angle g of attack. Upper surface is described by Lower surface is described by At angle of attack, upper surface slope, At angle l off attack tt k llower surface f slope, l Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 7 dZl dZ u x Cl 2 d dx dx c M 2 1 0 2 At =0 and 1, 1 (leading edge and trailing edge) So, Astonishing result! Neither thickness nor camber produced any lift in supersonic flow. Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 8 Drag Coefficient Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 9 Drag per unit span For small , (in radians) ie i.e. Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 10 Drag due to angle of attack, thickness and camber Consider a cambered airfoil at angle of attack. Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 11 Note: 1.Everything causes drag. 2.We can split up the airfoil at the angle of attack into (a): flat plate at AOA (b): camber line at zero AOA (c): thickness distribution at zero AOA Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 12 The slope of the airfoil surface is the sum of the slopes due to the angle of attack, tt k th the camber b andd the th thi thickness k di distribution. t ib ti Similarly, l 2 tl cl 2 tl cl 2 2 Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 13 Now, Giving, Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 14 Pitching Moment Pitching moment due to the net force at a distance x from the leading edge on an area (dx times 1) is Moment coefficient is Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 15 If we split as before into AOA, camber and thickness, we will find that a.the contribution of thickness is zero b.both AOA and camber cause pitching moment Aerodynamic Center It is the ppoint about which the ppitchingg moment is independent p of angle g of attack. The above equation shows that the aerodynamic center is at the mid chord. Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 16 Shock -Expansion technique The pressures on the airfoil surface can also be calculated using oblique shocks and P-M expansions. Note: at the trailing edge, there are a few conditions to be met. 1. same flow direction 2. same static pressure on both sides of the slip line This is the most exact way of calculating forces and moments. It is also the most tedious, but it is necessary ffor angles l > 5° . Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 17 Second order theory (Busemann's theory) If we retain terms of the order of This gives better results for results for , in our expression for , , than the linearized theory, but worse . Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 18 Supersonic Drag From the Performance Point of View Drag at supersonic speeds consists of •friction drag & pressure drag, •wave drag due to volume, •wave drag due to lift, •induced drag due to finite aspect ratio •and d other th miscellaneous i ll d drag it items (i (interference t f d drag, which hi h may b be partly tl included in pressure drag). For low drag, drag supersonic configurations tend to be long long, thin thin,slender. slender Drag at supersonic speeds is very dependent on configuration shape, relative size and locations of the components. Copyright 2004 Courtesy: Dr. B.Komerath Kulfan, BOEING Co. Narayanan 19 Source of Drag: Fluid Mechanics Point of View (1) Boundary Layer drag: laminar and turbulent Fluid molecules hitting the surface, and thus losing their momentum, then bouncing off and hitting other molecules zipping along in the flow. This is called "viscous viscous drag drag".. Clearly this is a bigger deal if this "momentum transfer" is a big part of the momentum of the flow. This momentum transfer is confined to a region near the surface, called the "boundary layer". This is whyy the "Reynolds y Number" is important: p it ggives a measure of how large g the inertial forces of the flow are, with respect to the viscous forces. When the Reynolds number is low (< ~ 100,000? ), viscous drag becomes very important. Generally, the Reynolds number for the flow over an airplane wing is quite large (20 million based on wing chord?), so viscous drag is not very significant in subsonic flight. It does become significant when other kinds of drag are minimized, and at high speeds every source of drag becomes important. We generally speak of "skin friction drag" in high speed flight, because the high temperatures created at the skin worry us. The temperature becomes high because the molecules which were going smoothly along in the flow now start getting bounced all over the place when they collide with the molecules bouncing off the surface, and their motion becomes chaotic: the kinetic energy is converted t d to t heat, h t andd the th flflow near the th surface f becomes b hot, h t andd transfers t f heat h t tto th the surface. Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 20 Note: E Even if the th external t l flow fl is i supersonic, i inside i id the th boundary b d layer l the th velocity l it decreases d to t zero. Potential flow theory looks at the flow outside the boundary layer (remember that we assumed "irrotational"? The boundary layer is certainly rotational), so viscous drag is not captured by potential flow theory. We have to use "common sense" tricks like the "Kutta condition" to figure out the "right"amount of rotation in the boundary layer to solve an aerodynamics problem. Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 21 (2) Pressure drag. drag The flow becomes distorted so that regions of low pressure occur on the downstream side, pulling the aircraft backwards. We try our best in aircraft design to avoid such regions. Examples of such regions are flow separation zones or "recirculation recirculation bubbles" bubbles , and wakes wakes. We try to make wakes as thin as we can, by keeping the low-momentum fluid in the boundary layer as close to the surface as possible. Pressure drag, drag in many cases cases, arises from viscosity, viscosity but its cure may be related to making the boundary layer turbulent, so that the flow remains attached. So, what you do to reduce skin friction drag (i.e., making the boundary layer less turbulent) may in fact increase your pressure dragg because the flow separates p over the aft pportions of the airfoil. For this reason,, it is a ggood idea to consider these types of drag separately. A flow separation region may be carried on a supersonic configuration, though of course the velocityy inside this region g mayy be low relative to the surface. An example p is the recirculation region formed over the wing of a winged re-entry vehicle when its control surfaces are deflected (Space Shuttle, X-33, or the X-38 Crew Return Vehicle) Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 22 (3) Drag due to shocks: Shocks are regions where the entropy goes up, and the stagnation pressure drops. Thus they cause drag. Shocks cause large amounts of drag: the entropy increases suddenly across them. This is because inside the sharply discontinuous shock, dissipative effects such as viscosity and heat conduction take away some of the energy of organized motion and convert it to the energy of the random, d chaotic h ti motion ti off gas molecules. l l Entropy rise shows up as a DROP in stagnation pressure. The entropy rise across a shock is related to the third power of the static pressure change, or the turning angle, whereas the drag coefficient in wave drag is proportional to the square of the turning angle. angle The drag by a shock of given static pressure ratio is thus considerably greater than the total wave drag due to several waves, waves each of small pressure ratio ratio. Moral: If you have to make waves in supersonic flow, make a series of small waves rather than one big one. This is used in designing wings, fuselages, and engine inlets. Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 23 (4) Wave Drag: This is a strange phenomenon which is very much felt on supersonic aircraft, but would not be anticipated without thinking of the differerence between subsonic and supersonic flows . Calculating Wave Drag: We calculated drag coefficients in supersonic flow, from the pressure coefficient distribution over an airfoil in supersonic p flow,, after assumingg that the flow was ppotential,, and neglecting g g boundaryy layer y effects. This is called "wave drag". It is a feature of supersonic flow. Disturbances in ideal supersonic flow propagate out to infinity, unchanged in amplitude. The energy of these disturbances must come from the kinetic energy of the flow flow. This is the source of the "wave wave drag drag". Wave drag increases as angle of attack (lift) increases. It also increases as thickness or camber or any other disturbance increases. increases Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 24 In subsonic potential flow, on the other hand, the passage of an object leaves no trace: conditions return to what theyy were before the object j came by. y This is because the disturbances from different portions of the airfoil cancel out as one goes away from the airfoil. Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 25 (5) Lift-Induced Drag Due to Finite Aspect Ratio ”Lift-induced Lift-induced drag drag", or "induced induced drag" drag . This is, is literally, literally drag induced by our efforts to generate lift. As we know, lift is simply any aerodynamic force perpendicular to the freestream, and any lift generation is accompanied by induced drag. We have seen how to calculate induced drag of wings in low low-speed speed flow. flow Is there lift-induced drag in supersonic flow? Well, any time you generate lift, you turn the flow, aandd tthere e e must ust be so somee pe penalty a ty assoc associated ated with t tthis. s Thiss will sshow o up in you your wave a e ddrag ag calculation. At the wingtips, g p the ppressure difference between the freestream and the upper pp and lower surfaces, causes the flow to turn in on the upper surface and out on the lower surface, just like in subsonic flow. This redirection of momentum is not recovered - it is left behind, and after the aircraft leaves, it forms tip vortices in the atmosphere, spinning away like little tornadoes. It was the burning of fuel that generated the energy now used to make air go round and round - that is drag, and it happened because of lift. Although the wing cannot “feel” the effect of these vortices, you can account for the lift loss and drag increase, by looking at how much energy is in the spinning vortices. Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 26 Drag Mechanisms: Comparison Between Subsonic and Supersonic Flow Type Mechanism Subsonic flow Supersonic Flow Viscosity in the boundary layer: Molecules bouncing off surface transfer their momentum change to the molecules in the stream, slowing them down. down Yes. Yes (boundary layer is still subsonic!!). Also, compressibility leads to substantial density change and temperature change: worsens drag. drag 1 b) Skin friction: Momentum transfer turbulent becomes chaotic as entire packets of fluid start moving across the boundary layer: High-speed flow comes closer l tto surface, f lleading di tto greater shear, hence greater drag. Yes Yes (b.l. still subsonic). Also, compressibility leads to substantial density change and temperature change: worsens drag. d 1 a) Skin friction: laminar Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath 27 Type 2. Pressure drag: Mechanism Subsonic flow Supersonic Flow Wakes and recirculation regions of low pressure Yes Yes (subsonic inside these regions) 3. Lift-induced Energy formerly contained in Yes drag. streamwise momentum, now goes into forming rotating regions of flow (tip vortices). Lift is lost as well, near the wing tips. b) 4. Wave drag Pressure disturbances not recovered by cancellation No Yes. 5. Shocks Entropy rise due to irreversible No sudden compression s is roughly proportional to the cube of the static t ti pressure change, h or th the cube b of turning angle for oblique shocks: 3 Yes Copyright 2004 Narayanan Komerath a) Wave drag increases with lift coefficient. Momentum redirection at the wing tips. 28