25 ppmr / September 2008 Perceived Environmental

Uncertainty in

Public Organizations

An Empirical Exploration

Rhys Andrews

Cardiff University

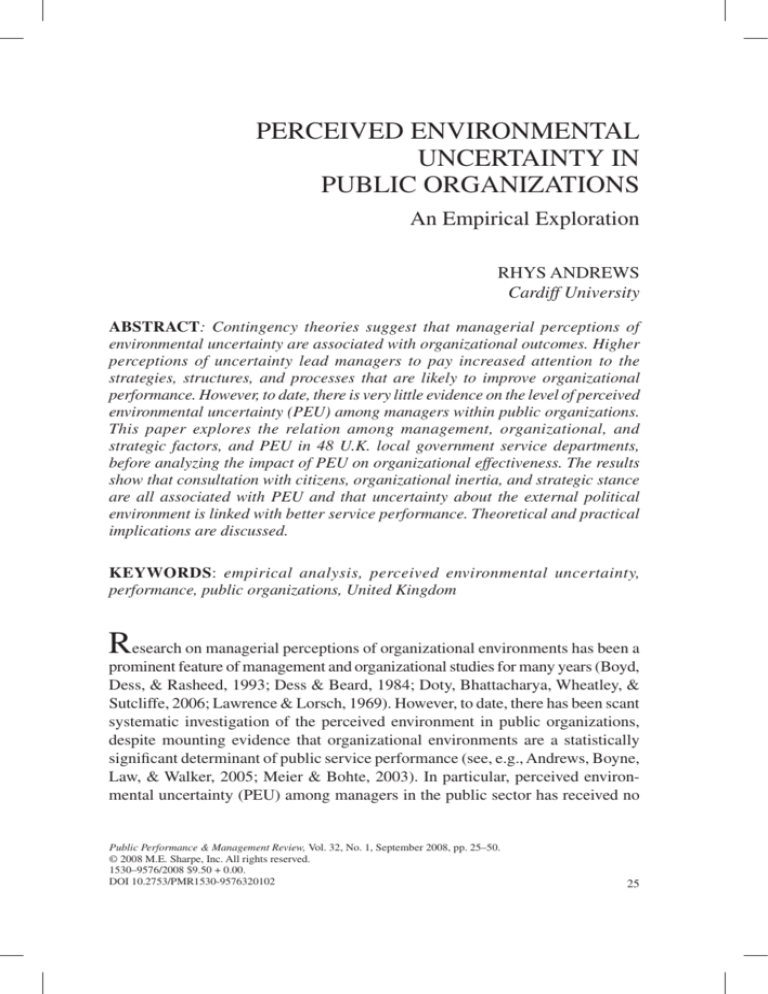

ABSTRACT: Contingency theories suggest that managerial perceptions of

environmental uncertainty are associated with organizational outcomes. Higher

perceptions of uncertainty lead managers to pay increased attention to the

strategies, structures, and processes that are likely to improve organizational

performance. However, to date, there is very little evidence on the level of perceived

environmental uncertainty (PEU) among managers within public organizations.

This paper explores the relation among management, organizational, and

strategic factors, and PEU in 48 U.K. local government service departments,

before analyzing the impact of PEU on organizational effectiveness. The results

show that consultation with citizens, organizational inertia, and strategic stance

are all associated with PEU and that uncertainty about the external political

environment is linked with better service performance. Theoretical and practical

implications are discussed.

KEYWORDS: empirical analysis, perceived environmental uncertainty,

performance, public organizations, United Kingdom

R

esearch on managerial perceptions of organizational environments has been a

prominent feature of management and organizational studies for many years (Boyd,

Dess, & Rasheed, 1993; Dess & Beard, 1984; Doty, Bhattacharya, Wheatley, &

Sutcliffe, 2006; Lawrence & Lorsch, 1969). However, to date, there has been scant

systematic investigation of the perceived environment in public organizations,

despite mounting evidence that organizational environments are a statistically

significant determinant of public service performance (see, e.g., Andrews, Boyne,

Law, & Walker, 2005; Meier & Bohte, 2003). In particular, perceived environmental uncertainty (PEU) among managers in the public sector has received no

Public Performance & Management Review, Vol. 32, No. 1, September 2008, pp. 25–50.

© 2008 M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved.

1530–9576/2008 $9.50 + 0.00.

DOI 10.2753/PMR1530-9576320102

25

26 ppmr / September 2008 attention, even though it is recognized to be a critical issue in management theory

(Buchko, 1994; Duncan, 1972; Milliken, 1987). This article seeks to address this

gap in the literature on public organizations by exploring PEU in local government service departments.

PEU is a product of managers’ perceptions of the combined complexity, instability, and unpredictability in the organizational environment. An environment that

is perceived to be complex, changing rapidly, and difficult to predict creates high

levels of uncertainty about the appropriate organizational responses to external

circumstances. As a result, managers are forced to consider carefully the impact

of their actions and decisions. PEU is thus a concept chiefly associated with contingency theories (Donaldson, 2001; Miles & Snow, 1978).

Scholars such as Chandler (1962) and Child (1972) have claimed that managers

make strategic choices based on the assessment of the environmental conditions

that they face. Miles and Snow (1978) later refined this argument to suggest that

organizational performance is dependent on the adoption of a consistent strategy

for aligning an organization with its environment. The successful adoption of the

correct strategy in these circumstances was intimately related to perceptions of

environmental uncertainty among managers. High levels of managerial PEU would

reflect a heightened sensitivity to the external constraints surrounding an organization and thereby be associated with strategies and structures that were likely to

maximize performance. By contrast, low levels of PEU reflect an underestimation

of organizational contingencies that would be revealed in a mismatch between

strategy, structure, and environment, ultimately resulting in poor performance.

The significance of the strategy–environment link for organizational effectiveness

thus makes the extent of perceived environmental uncertainty a critical concern

for public management scholars. Indeed, evidence from private organizations

suggests that higher levels of PEU are associated with increased environmental

scanning and innovation, which, in turn, lead to better organizational outcomes

(Daft, Sormunen, & Parks, 1988; Ozsomer, Calantone, & Di Benedetto, 1997;

Russell & Russell, 1992).

Environmental Uncertainty in Public Organizations

Concepts and measures of environmental uncertainty have conventionally focused

on how key organizational stakeholders perceive certain features of their organizational environments. Although such subjective measures of the environment

can be criticized for their lack of correspondence with more objective archival

measures (Tosi, Aldag, & Storey, 1973), it is only by using such perceptual measures that researchers can accurately tap the linkages between uncertainty and

managerial choices proposed by contingency theorists. These unique aspects of

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 27

organizational behavior lie beyond the reach of aggregated secondary data drawn

from archival sources. Indeed, managers’ perceptions of the environment are in

many respects more important than the actual environment, as it is perceptions

of external circumstances rather than objective indicators of those conditions that

organizational decision makers act on (Weick, 1969).

Classic work on organizational environments (Duncan, 1972; Jurkovich, 1974;

Terreberry, 1968) suggests that managerial perceptions of the simple–complex

and static–dynamic dimensions of the environment are the most significant determinants of the perceived uncertainty of external circumstances, which makes

it especially important to investigate the combined effects of perceived complexity and dynamism when considering PEU. The combination of these dimensions

also has special relevance for the conceptualization and measurement of PEU in

public organizations, where the complexity, instability, and unpredictability of the

environment they confront are arguably defining characteristics of their publicness (see Boyne, 2002). A conceptual model of PEU in public organizations can

thus be developed by drawing on the literature on environmental complexity and

dynamism.

Environmental Complexity and Dynamism

Environmental complexity is a product of the relative heterogeneity and dispersion

of an organization’s domain (Dess & Beard, 1984). Heterogeneity is present when

organizations grapple with a wide range of markets and services, which increases

the need for information-processing skills and systems, thereby placing greater

strain on the resource capacity of an organization (Dutton, Fahey, & Narayanan,

1983). Organizations providing services across a broad domain face a dispersed

environment. In these circumstances, the costs associated with strategic management and strong partnerships with suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders

are high (Aldrich, 1979). By contrast, the benefits from interdependence (such as

multioutput production) accrue more quickly when services are concentrated in

a narrow domain (Starbuck, 1976). The environment faced by public organizations is especially complex because they are required to meet the demands of a

diverse range of (often widely dispersed) client groups and external stakeholders.

Perceived complexity in the public sector is, therefore, likely to reflect managers’ assessments of the relative homogeneity and dispersion of the service users,

citizens, and external agencies with whom they interact.

Environmental dynamism is a product of the rate of change in external circumstances (instability), and the unpredictability (or turbulence) of that change

(Terreberry, 1968). Organizations typically seek to cope with environmental

turbulence and instability through better strategic management (Dess & Beard,

28 ppmr / September 2008 1984). In the public sector, policymakers have claimed that the impact of environmental dynamism can be reduced through improved planning and corporate

coordination (Office of Public Services Reform, 2002). Although major shifts in

the socioeconomic and external political environments of public organizations are

often known in advance (e.g., demographic change and new policy initiatives),

perceived deviations from expected environmental changes are still likely to have

an important influence on public organizations. For example, environmental jolts,

such as natural disasters or political crises, may place additional burdens on an

organization’s capacity to perceive and manage uncertainty (Meyer, 1982).

Daft (2001) argued that PEU is the product of managers’ perceptions of environmental complexity and dynamism in combination. Perceptions of complexity

increase uncertainty by placing greater demands on the ability of managers to

interpret how to meet potentially conflicting demands within the environment. An

unpredictable and rapidly changing environment intensifies the need for managers

to manage the circumstances they confront proactively. Taken together, the highest

level of PEU possible is, therefore, found when managers perceive high levels of

complexity, instability, and unpredictability. According to contingency theorists,

managers who are able to recognize high levels of complexity and dynamism in

the environment are more likely to manage uncertainty better than those who do

not. For instance, Downey and Slocum (1975) argued that cognitive biases associated with low tolerance of ambiguity lead to the underestimation of environmental

complexity, instability, and unpredictability, which, in turn, is likely to result in

poor decision making. In the public sector, the increasing interconnectedness of

demographic diversity and change, as well as the growth of multiorganizational

and multigovernmental networks, places ever greater burdens on public managers to perceive and manage uncertainty. This complexity makes it particularly

important for researchers to systematically theorize, measure, and investigate

PEU in public organizations.

Harris (2004) claimed that a successful conceptualization of the organizational environment should meet four key criteria: empirical testability, temporal

validity, international generalizability, and predictive validity. The framework

for exploring PEU that I present here is empirically testable, because suitable

measures of managerial perceptions of environmental complexity, instability, and

unpredictability are available or can be developed and applied. It exhibits temporal

validity because PEU in the public sector is an issue of perennial importance,

which also means that the framework is generalizable to public organizations

in other nations where managers are also likely to experience high levels of environmental uncertainty. Furthermore, it is capable of demonstrating predictive

validity in that PEU can be modeled on a host of relevant organizational inputs,

outputs, and outcomes.

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 29

Exploring PEU in Public Organizations

Internal Factors

Management

Buffering their organizations from environmental shocks is an important task for

public managers (O’Toole & Meier, 1999). However, excessive buffering may

lead managers to run the risk of becoming too insulated from external circumstances, potentially causing environmental misperception. This buffering effect

makes managerial efforts to learn about and exploit opportunities within the

environment a critical task. One important way in which public managers can

accomplish this task is through the cultivation of collaborative governance with

a range of relevant external actors and agencies (see, e.g., Agranoff, 2005; Meier

& O’Toole, 2003). Collaborative governance arrangements are characterized by

multiple, overlapping partnerships between various combinations of public, private, and voluntary organizations. Proactive management of these arrangements is

likely to reflect a greater sensitivity to the external context spurred by a deliberate

strategy of “high uncertainty avoidance” (Goerdel, 2006, p. 353), which leads to

my first hypothesis:

H1: Collaborative governance is positively related to PEU.

Public organizations require the support of external stakeholders other than their

partners in collaborative governance arrangements. In particular, local citizens may

dictate agenda setting or constrain the range of alternatives available to policymakers (Elkins & Simeon, 1979). Better communication with citizens can help generate

trust and confidence in public organizations and increase responsiveness to local

needs by improving the quality of information on customer preferences (Berman,

1997; Swindell & Kelly, 2000). By managing outward in this manner, managers

may be able to gain a broader sense of the variety of external contingencies faced

by their organizations. Hence:

H2: Consultation with local citizens is positively related to PEU.

Organization

Organizations that are unable to manage their external environment are arguably

plagued by internal inertia, that is, a general inability to break free from outdated

or inadequate routines. Such a lack of responsiveness is often associated with

hierarchical organizational structures. Centralized decision making, in particular,

has been linked with reliance on complicated information systems and an overall

preference for internal rather than external communication, thereby preventing

swift or effective adjustments to environmental change (Katz, 1982). By contrast,

30 ppmr / September 2008 less hierarchical organizations may be able to draw on a wider range of informal

channels of internal and external information to both respond to and shape environmental change. For example, in the public sector, street-level bureaucrats (e.g.,

teachers, police officers, and social workers) have more regular contact with clients

and are, therefore, able to exercise considerable discretion in their dealings with

them (Lipsky, 1980). As a result, managers in decentralized organizations may be

more likely to perceive high levels of environmental complexity and dynamism.

Thus, the third hypothesis is:

H3. Decentralized decision making is positively related to PEU.

A further aspect of organizational inertia that may affect managerial perceptions of the environment is the relative level of autonomy of their organization

from bureaucratic control. Autonomy can give organizations greater leeway in

how they choose to respond to external challenges, enabling them to buffer threats

and exploit opportunities as they see fit. However, high levels of autonomy may

make it less urgent for managers to perceive accurately and respond appropriately

to environmental variations, as they are likely to be subjected to fewer regulatory

pressures from political principals. Indeed, high levels of organizational autonomy

in some public organizations have been associated with insular decision making

and managerial complacency (Rainey & Steinbauer, 1999). Therefore:

H4: Organizational autonomy is negatively related to PEU.

The recent performance of organizations may be linked with relative inertia due

to its impact on the efforts of decision makers to effect strategic change (Ketchen

& Palmer, 1999). Managers’ perceptions of organizational performance are,

therefore, likely to be related to the levels of PEU that they experience. If managers perceive their organizations to be underperforming, they may have a keener

sense of the need to develop and implement innovative strategies in response to

external contingencies. By contrast, perceptions of high performance may prevent

managers from recognizing serious environmental threats (Staw, Sandelands, &

Dutton, 1981). As a result:

H5: Perceived performance is negatively related to PEU.

Strategy

Miles and Snow’s (1978) classic strategy typology associates different strategic

stances with varying managerial assumptions regarding the environment. Prospecting organizations “almost continually search for market opportunities, and . . .

regularly experiment with potential responses to emerging environmental trends”

and so perceive the environment to be constantly changing (p. 29). By contrast,

defending organizations “devote primary attention to improving the efficiency of

their existing operations” and, therefore, concentrate on optimizing performance

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 31

on core tasks (p. 29). Consequently, they tend to view the environment as simple

and stable because their focus is on refining internal operations. Reacting organizations, however, rarely alter their managerial processes “until forced to do so

by environmental pressures” and thus regard the organizational environment as

unpredictable (Miles & Snow, 1978, p. 29). The varying approaches to assessing

and managing the environment associated with these different strategies lead to:

H6: Strategies of prospecting and reacting are positively related to PEU,

but a strategy of defending is negatively related to PEU.

Organizational Effectiveness

Managers’ perceptions of environmental uncertainty are likely to reflect the

extent to which they understand how the external degree of difficulty constrains

their ability to deliver services. In such circumstances, managers may be more

committed to enhancing the ability of their organization to cope with exogenous

pressures, leading them to avert the potential pitfall of threat-rigidity. High levels

of PEU may reflect a thorough knowledge of clients’ widely differing needs, the

competing values held by external stakeholders (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1981), and

the problems associated with the goal ambiguity of both these causes (Chun &

Rainey, 2005). Realistic assessments of these wicked issues in the socioeconomic

and external political context facing a public organization, therefore, suggest the

following hypothesis:

H7: Organizational effectiveness is positively related to PEU.

Data and Methods

The organizational context of the analysis is local government service departments

in Wales. Welsh local governments provide education, social care, housing, welfare

benefits, environmental, and leisure and cultural services and are governed by

elected bodies with a Westminster-style cabinet system of political management. In

such a system, the cabinet represents the de facto executive branch of government

and usually comprises senior members of the ruling political party, all of whom

collectively decide policy. By restricting the analysis to service departments, other

potential influences on PEU such as the policies of higher tiers of government and

legal constraints are held constant. Some cases could not be matched when the

explanatory variables were mapped on to the dependent variables, due to missing

data within the respective datasets. As a result, the statistical analysis is conducted

on 48 cases, consisting of 9 education departments, 6 social services departments,

6 housing departments, 8 highways departments, 9 public protection departments,

and 10 benefits and revenues departments.

Data on perceptions of the environment, management, organizational, and

32 ppmr / September 2008 strategic factors are derived from an electronic survey of managers in Welsh local government conducted in autumn 2002. E-mail addresses for up to 10 senior

and middle managers in every service department were provided by the corporate

policy unit in each government. Questionnaires were then distributed via e-mail.

Survey respondents were asked a series of questions about their organizations. For

each question, informants placed their service department on a seven-point Likert

scale ranging from 1 (disagree with the statement) to 7 (agree with the statement).

Data were collected from different tiers of management to circumvent sample

bias problems associated with surveying informants from only one organizational

level. Heads of service and middle managers were selected for the survey because

attitudes often differ between hierarchical levels within organizations (Walker &

Enticott, 2004).

The sampling frame for the survey consisted of 198 service departments and

830 informants. Responses were received from 46 percent of services (n = 90) and

29 percent of individual informants (n = 237). The sample of 48 service departments analyzed represents 36 percent of a possible 132 education, social services,

housing, highways, public protection, and benefits departments—a rate similar to

studies of strategic management in the private sector (e.g., Gomez-Mejia, 1992).

The departments analyzed are representative of the diverse operating environments faced by Welsh local governments, including urban, rural, socioeconomically deprived, and predominantly English- or Welsh-speaking areas. Time trend

extrapolation tests uncovered no statistically significant differences between early

and late respondents, indicating that nonrespondent bias is not a problem. This

estimation technique is commonly used in survey research because late respondents

demonstrate a reluctance to respond, which is akin to nonresponse (see Armstrong

& Overton, 1977, for an explanation and application).

To generate service level data suitable for analysis, informants’ responses

within each service department were aggregated. The average score was taken

as representative of that service. Thus, for instance, if there were two informants

from a highways department, one from road repair services, and another from

traffic planning services, the mean of their responses was used.

Dependent Variables

Perceived Environmental Uncertainty

Six items from the survey gauged perceptions of environmental complexity and

dynamism (see Table 1). To measure perceived complexity, respondents were asked

to score the relative complexity of both the socioeconomic and external political

contexts they faced on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree with the proposed statement) to 7 (agree with the proposed statement). Similarly, perceived

dynamism was measured by asking them to evaluate the extent to which these two

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 33

contexts were (a) unpredictable and (b) changing rapidly. Because it is possible for

an organization to face a changing but predictable environment, the perceptions

of instability and unpredictability were multiplied to construct variables reflecting

more accurately their interactive effects on perceived environmental dynamism.

To generate measures of overall socioeconomic and external political PEU,

the respective measures of perceived complexity and dynamism were multiplied

together. Again, the rationale for multiplying rather than summing complexity and

dynamism is simply that an organization’s environment reflects the interaction of

both dimensions. Organizational environments can be complex but comparatively

static. In such circumstances, PEU may be relatively low as managers are able to

predict the level of complexity that they face (Jurkovich, 1974). Therefore, it is

important to account for the combined effects of perceived complexity and dynamism when exploring the relation between PEU and organizational characteristics

and outcomes. Skewness and kurtosis tests reveal that the interacted measures

are normally distributed. Very high PEU scores are, therefore, unlikely to have

distorted the statistical results.

Organizational Effectiveness

The performance of Welsh local government services is evaluated every year

through statutory performance indicators set by the National Assembly for Wales

(i.e., their most powerful stakeholder). The National Assembly for Wales Performance Indicators (NAWPIs) are based on common definitions and data, which are

obtained by councils for the same time period with uniform collection procedures

before being independently verified. For this analysis, 29 of the 100 NAWPIs

available for 2003 that focus most closely on effectiveness were used. Examples

include the average General Certificate in Secondary Education (GCSE) score,

the number of pedestrians killed or seriously injured in road accidents, and the

percentage of welfare benefit renewal claims processed on time (see the Appendix for the full list). To standardize the NAWPIs for comparative analysis across

different service areas, z-scores are taken of each performance indicator for all

Welsh governments. Different indicators within each service area are then added

together to produce an average score, before being combined with other service

scores to create an aggregate measure of organizational effectiveness.

Independent Variables

Internal Factors

Management. The relative level of collaborative governance in Welsh local government service departments is measured by creating a single factor using principal

components analysis of three survey items asking respondents to indicate whether

they worked with (a) other local and public authorities, (b) the private sector, or

Dependent variables

Perceived socioeconomic uncertainty:

The socioeconomic context the service operates in

is very complex.

is unpredictable.

is changing rapidly.

Perceived external political uncertainty:

The external political context the service operates in:

is very complex.

is unpredictable.

is changing rapidly.

Organizational effectiveness 2003

Independent variables

Management factors:

The service works in partnership with other local or public authorities.

The service works in partnership with the voluntary sector.

The service works in partnership with the private sector.

Strategy develops through consultation with local citizens.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

4.00

2.00

1.00

1.00

4.00

2.00

1.00

2.00

–1.56

3.00

1.00

1.00

2.00

4.92

3.40

3.71

110.55

5.08

4.12

4.61

.04

5.40

4.97

4.37

4.41

Min

69.85

Mean

7.00

7.00

7.00

7.00

7.00

6.00

7.00

1.34

7.00

6.00

6.00

252.00

216.00

Max

.96

1.44

1.29

1.16

1.24

1.26

1.33

.57

1.19

1.19

1.29

67.25

48.82

Std. dev.

34 ppmr / September 2008 7.00

7.00

7.00

7.00

7.00

2.12

1.54

2.40

40.02

1326.01

223,301

726.32

1.00

1.00

2.00

2.00

2.00

4.00

–1.51

–1.43

12.31

353.27

66,829

24.25

.68

.98

7.13

205.17

38,244.66

242.82

.86

1.20

1.06

1.48

1.26

.88

Note: The diversity measure consists of 16 ethnic groups: White British, Irish, Other White, White and Black Caribbean, White and Black African, White and

Asian, Other Mixed, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Other Asian, Caribbean, African, Other Black, Chinese, Other Ethnic Group.

Sources: Data for organizational effectiveness and service expenditure (2001–2003), deprivation, ethnic diversity, population, and population density come

from National Assembly for Wales (2003, 2004), Department of Environment, Transport, and Regions (2000), and Office for National Statistics (2003).

Organizational factors

All staff are involved in the strategy-making process to some degree.

4.67

Our service has more autonomy than other services in the authority.

4.15

Perceived overall performance 2002

5.36

Strategy factors

Searching for new opportunities for service delivery is a major part of our

overall strategy.

4.87

The service emphasizes efficiency of provision.

5.15

The service explores new opportunities only when under pressure from external

agencies.

1.00

Controls

Organizational effectiveness 2002

.03

Service expenditure 2002

.01

Deprivation 2001

23.85

Ethnic diversity 2001

582.41

Population 2001

131,465

Population density 2001

355.51

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 35

36 ppmr / September 2008 (c) the voluntary sector. The factor explains over 60 percent of the variance in the

items, and the factor loadings for each aspect of collaborative governance were all

above 0.7, indicating that they are important determinants of the variance explained

by the factor. It also has a good Cronbach’s alpha internal reliability score of 0.7

(Nunnally, 1978). The role of citizen consultation within service departments is

measured using an item that gauges the extent to which strategy develops through

consultation with local citizens.

Organization. Most studies of organizational structure in the private sector

measure the extent of centralization by assessing the degree of participation in

decision making (Hage & Aiken, 1967, p. 77). The measure of organizational decentralization used in this study is, therefore, based on a variable that evaluates the

extent of involvement in strategic decision making within the sample organizations.

Organizational inertia is also measured as both a function of the relative autonomy

and the perceived performance of service departments. Autonomy is gauged by

asking respondents to indicate the extent to which their service department had

more autonomy than other services in the authority. High levels of occupational

closure within multipurpose public organizations may buffer service departments

from unpredictable external shocks and intrusive bureaucratic control (Kitchener,

2000). Managerial perceptions of performance were assessed by posing a question

based on Dess and Robinson’s (1984) study of manufacturing firms: “Overall, to

what extent would you agree that your service is performing well?” Perceptions

of high performance are likely to lead organizational decision makers to rely on

automatic interpretations of environmental circumstances based on past diagnoses

(Dutton, 1993).

Strategic stance. The measures of organizational strategy are derived from

Snow and Hrebiniak (1980) and Stevens and McGowan (1983). A prospector

strategy is operationalized through a survey item asking respondents to indicate

if their service is at the forefront of innovative approaches. To explore the extent

to which Welsh local governments displayed defender characteristics, informants

were asked whether their service emphasizes efficiency of provision. Reactors

are expected to lack a consistent strategy and to await guidance on how to manage and deliver services. Informants were, therefore, asked about the extent to

which they explored new opportunities only when under pressure from external

agencies.

Controls

Past performance. The performance of public organizations changes only incrementally over time (O’Toole & Meier, 1999), which indicates that performance

in one period is strongly influenced by performance in the past. Consequently,

effectiveness in the previous year is entered in the analysis of organizational effectiveness in 2002–3. By including the autoregressive term, the coefficients for

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 37

socioeconomic and external political PEU show what these variables have added

to (or subtracted from) the performance baseline.

Service expenditure. Performance may vary because of the financial resources

expended on services (Boyne, 2003). Spending variations across services may

arise for a number of reasons (e.g., the level of central government support, the

size of the local tax base, and departmental shares of a government’s total budget). Potential expenditure effects are controlled by using figures drawn from the

2001–2 NAWPIs (see the Appendix).

External constraints. Previous research has shown that the achievements of local governments are affected by the environment in which they operate (Andrews

et al., 2005). As a result, four objective measures of the external environment

faced by service departments are included in the statistical model of performance.

The average Ward score on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (Department of

Environment, Transport, and Regions, 2000) is used as a measure of the quantity

of service need. This score, which is the standard population-weighted measure

of deprivation used by U.K. central government, is derived from 33 indicators

across six domains (e.g., levels of income, education, and health). Residents in

disadvantaged areas scoring highly in the index of deprivation typically have fewer

social and economic resources with which to boost service provision through

coproduction (Williams, 2003).

To measure diversity of service need, the proportion of each ethnic group within

a local government area is squared and the sum of the squares of these proportions

subtracted from 10,000. The resulting measures are the equivalent of the Herfindahl

indices used by economists to measure market concentration, with a high level

of diversity reflected in a high score. Public organizations operating in ethnically

diverse areas may require a wider range of costly specialist social services, such as

multilingual community workers, and also need to assign considerable resources to

building good community relations (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 2003).

Indeed, controlling for this aspect of social heterogeneity, rather than economic or

educational diversity, is especially important, because of the substantial scholarly

and governmental attention devoted to addressing its consequences (e.g., Jencks

& Phillips, 1998; Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 2003). Log transformation

of the measure counter the effects of positive skew (test result of 2.2).

Large organizations can accrue scale economies by distributing fixed costs over

more units of output (Stigler, 1958), which can, in turn, enable them to reinvest

the savings in new or innovative ways of working that may improve performance.

The relative size of local government service departments is fixed by the territorial

boundaries of the population they serve. Organizational size is, therefore, measured using population figures for each local government. These figures are then

divided by the area in square kilometers to give a measure of population density.

Providing services within densely populated areas can generate scope economies,

38 ppmr / September 2008 as static facilities in urban locations can offer multiple services from the same site

(Grosskopf & Yaisawamg, 1990). The descriptive statistics and data sources for

all the measures are listed in Table 1.

Statistical Results

The results of the statistical models of PEU are shown in Table 2. The average

variance inflation factor for the independent variables is around 1.6. It is, therefore,

highly unlikely that the results are distorted by multicollinearity (Bowerman &

O’Connell, 1990). Robust estimation of the regression standard errors was used

to correct for nonconstant error variance (Long & Ervin, 2000).

Management, organizational, and strategic variables collectively explain over

37 percent of the variation in socioeconomic and external political PEU in Welsh

local government service departments. The evidence suggests that strategic factors

have a fairly consistent association with both dimensions of PEU. However, the

evidence on management and organizational factors is more mixed.

Hypothesis 1 is not confirmed by the results: The coefficient for the collaborative governance factor is statistically insignificant for both measures of PEU. This

finding corroborates evidence that the benefits of collaborative governance, in

terms of knowledge and information sharing, may not be as great as anticipated

(Zhang & Dawes, 2006). However, it is possible that the effects of the different

dimensions of collaborative governance are canceling each other out. That is,

that partnership with one sector is more likely to heighten PEU in organizations,

whereas partnership with another is likely to reduce levels of PEU. For example,

Parker and Hartley stressed that collaboration with private organizations can generate substantial transaction costs “arising from incomplete information” (2003,

p. 107). We might then expect partnership with the private sector to be positively

associated with PEU. However, disaggregating the separate aspects of the collaborative governance factor did not lead to changes in the explanatory power of

the model or uncover new statistically significant relations.

Hypothesis 2 receives extremely mixed support: The sign of the coefficient

for citizen consultation is positive and statistically significant for socioeconomic

PEU but is negative and significant for external political PEU. On the one hand,

organizations that consult with citizens may develop a keener sense of the diverse

social needs that they confront, intensifying their uncertainty about meeting the

competing demands that these make. For example, to consult different citizen

groups, particular efforts are required to reach those experiencing poverty or social exclusion (Barnes, Newman, Knops, & Sullivan, 2003). On the other hand,

by directly consulting citizens, public organizations may be displaying a greater

propensity to trust them and, correspondingly, perceive local political demands

to be more certain (Yang & Callahan, 2005). In either case, it is clear from the

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 39

Table 2. Internal Factors Associated with Perceived

Environmental Uncertainty (PEU)

Socioeconomic PEU

External political PEU

Independent variables

Slope

Slope

s.e.

Constant

Management

Collaborative

governance

Citizen consultation

Organization

Decentralization

Autonomy

Perceived

performance

Strategic stance

Prospector

Defender

Reactor

F statistic

R2

–48.662

147.021

96.318

s.e.

56.642

3.034

8.135*

5.520

4.484

–2.743

–16.120**

8.885

7.085

7.653**

–2.642

3.453

3.815

2.677

–13.322**

5.207

6.454

6.280

2.021

9.896

5.542

5.174

7.665

29.052***

–25.034***

23.427**

2.857**

.370

8.332

8.031

11.765

–10.588*

11.098**

.578

23.039***

3.067***

.386

Note: N = 48.

***p ≤ 0.01. **p ≤ 0.05. *p ≤ 0.10 (two-tailed tests).

results that engaging with citizens is strongly associated with the environmental

perceptions of local government service departments.

Hypothesis 3 receives partial support. Decentralized decision making appears

to increase levels of socioeconomic PEU. However, the results suggest it has no

statistically significant effect on external political PEU. One potential explanation

for this finding is that by involving staff from lower levels, it is possible for an

organization to tap into particular aspects of their local knowledge, but that there

maybe limits to that knowledge. Organizational members that are closer to the

front line of operations are likely to have a sure grasp of the heterogeneity and

unpredictability of client needs in the public sector, but their distance from political principals may lead them to be less aware of the demands of other important

external stakeholders. For example, street-level bureaucrats who are “savvy about

what works as a result of daily interactions with clients” are rarely involved in

the external political relations of their parent organizations (Maynard-Moody,

Musheno, & Palumbo, 1990, p. 845).

The results provide mixed support for Hypothesis 4. The sign for the organizational autonomy coefficient is negative in both cases but is only statistically

significant for external political PEU. By contrast, Hypothesis 5 is confirmed for

40 ppmr / September 2008 socioeconomic PEU but not for external political PEU. The evidence on these

organizational factors suggests that service departments that are buffered from

external interference through having greater freedom to maneuver than their less

autonomous counterparts are likely to perceive their external political circumstances to be more certain. In contradistinction, those organizations perceiving

themselves to be high performers appear to feel that they have a surer grasp of the

social and economic circumstances with which they contend. Both findings imply

that organizations may become more complacent about environmental challenges

if they perceive themselves to be insulated from important socioeconomic and

external political pressures. For example, the precipitous decline of the prestigious

and successful U.K. retailer Marks and Spencer during the 1990s coincided with

a failure to respond to concerns about service quality voiced in customer surveys

(Mellahi, Jackson, & Sparks, 2002).

The hypothesis on strategic factors (Hypothesis 6) receives strong support from

the statistical results. In line with the propositions, the coefficient for a strategy

of prospecting is consistently positive and statistically significant. Similarly, the

sign for the reacting coefficient is positive and statistically significant for both

measures of PEU. In addition, the proposition on defending receives some confirmation from the results: Its coefficient is negative and statistically significant

for external political PEU. Prospecting is generally associated with a high level of

PEU by contingency theorists. Innovative organizations that seek to identify new

opportunities typically perceive their external circumstances to be both complex

and dynamic (Russell & Russell, 1992). A reacting strategy may lead managers to

become highly sensitive to rapid environmental changes as their decision making

would need to be attuned to cues from external forces, especially those given by

their political principals (Rainey, 1997). By contrast, defenders are inward looking

and may be more inclined to perceive their environment as stable, simple, and

predictable even if evidence is available to suggest that this is not the case.

The results of the statistical model of PEU and organizational effectiveness using

robust estimation of the regression standard errors are shown in Table 3. The results

are unlikely to be distorted by multicollinearity as the average variance inflation

factor for the independent variables is about 1.4 (Bowerman & O’Connell, 1990).

The model provides an excellent level of statistical explanation of variations in

the performance of Welsh local government service departments. The R2 is above

80 percent and is significant at 0.01. Furthermore, the control variables have the

expected signs, and most are statistically significant. Performance is autoregressive, quantity and diversity of service need, as expected, have a significant negative

association with performance, and population density has a significant positive

association. Taken together, the R2 and the effects of the performance baseline,

service expenditure, and external constraints suggest that the model provides a

sound foundation for assessing the consequences of PEU.

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 41

Table 3. Perceived Environmental Uncertainty (PEU)

and Organizational Effectiveness

Effectiveness

Independent variables

Constant

Perceived socioeconomic uncertainty

Perceived external political uncertainty

Past performance

Service expenditure

Ethnic diversity (log)

Deprivation

Population

Population density

F statistic

R2

Slope

3.678***

–.0008

.001**

.792***

.060

–1.152***

–.035***

.000001

.0004**

20.612***

.809

s.e.

1.185

.0008

.0006

.065

.041

.400

.008

.000001

.0002

Note: N = 48.

***p ≤ 0.01. **p ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed tests).

Hypothesis 7 is given partial support by the findings presented in Table 3. The

coefficient for external political PEU is positive and statistically significant, and

the coefficient for socioeconomic PEU is statistically insignificant. Local government service departments that perceive high levels of uncertainty in their external

political environment perform better than those that perceive that environment to

be certain. However, perceptions of the relative level of uncertainty in the social

and economic circumstances are unrelated to their service achievements.

Even when controlling for past performance, service expenditure, and external

constraints, perceptions of external political uncertainty appear to stimulate better

performance. There are a number of potential explanations for this finding. It is

conceivable that managers in high-performing public organizations are acutely

aware of uncertainty in the external political environment and are, as a result, far

less complacent about the need to secure institutional legitimacy. For instance,

they may be more willing to devote greater resources to meeting the demands

made of them by important political principals or to improving community relations within the local population. By contrast, underestimation of the external

political context may lead to insular decision making or an inability to respond

effectively to political exigencies. Institutional theory suggests that organizations

that are confident of their legitimacy may erroneously associate that with better

performance (Frumkin & Galaskiewicz, 2004). It is also possible that simply having a heightened sensitivity to the wide range of external stakeholders within the

environment of public organizations may make public managers approach their

42 ppmr / September 2008 Table 4. Summary of Findings

Findings

Variable

Management

Collaborative governance

Citizen consultation

Organization

Decentralization

Autonomy

Perceived performance

Strategic stance

Prospector

Defender

Reactor

Effectiveness

Service performance

Hypothesized

direction

Socioeconomic

PEU

External political

PEU

+

+

ns

+

ns

–

+

–

–

+

ns

–

ns

–

ns

+

–

+

+

ns

+

+

–

+

+

ns

+

Note: PEU = perceived environmental uncertainty.

task in a manner that is conducive to better service performance. For example,

they may increase the intensity of their networking with relevant external agencies

to reduce the impact of uncertainty (Meier & O’Toole, 2001).

The findings on perceived socioeconomic PEU suggest that managers’ perceptions of complexity, instability, and unpredictability in the social and economic

circumstances they face are unrelated to public service performance. However, this

result does not necessarily mean that this dimension of PEU simply does not affect

the achievements of public organizations. It is possible that managers’ perceptions

of social and economic uncertainty are associated with strategies, structures, or

processes that may, in turn, lead to better performance. The combined effect of

PEU and internal organizational characteristics on performance is a topic meriting further research.

The overall results of the hypothesis testing are summarized in Table 4. For the

most part, the empirical findings support the hypotheses. The results show that over

one-half of the results (10 out of 18) are statistically significant in the predicted

direction. However, nearly one-third of the findings are statistically insignificant,

suggesting that there is a need to explore certain aspects of PEU in more depth,

especially its hypothesized relation with collaborative governance. Furthermore,

one hypothesis is contradicted: Citizen consultation is negatively associated with

external political PEU. Nonetheless, the results confirm the value of the concept

of PEU for the empirical analysis of public organization behavior. By analyzing

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 43

the relations between PEU and the organizational choices and outcomes proposed

by contingency theorists, researchers can gain a valuable perspective on the ways

in which “environmental forces mold organizations through the mediation of human minds” (Simon, 1976, p. 334).

Conclusion

This paper examines PEU in public organizations by exploring its relation with

internal factors and organizational outcomes in Welsh local government service

departments. Levels of PEU are strongly associated with strategic stance: A prospecting or reacting strategy is positively related to socioeconomic and external

political uncertainty, whereas a strategy of defending is negatively related to

external political uncertainty. Citizen consultation and organizational inertia are

also associated with PEU. In turn, the performance of local government service

departments is positively influenced by perceived external political uncertainty,

even when controlling for past performance and a range of external constraints.

This analysis expands on work on organizational environments in the public

sector in several ways. First, it formalizes and tests a model of the organizational

characteristics and outcomes associated with PEU. Previous studies have so far

only theorized the concept of PEU in public organizations (Begun & Kaissi,

2004). Second, the paper presents systematic empirical evidence on managerial

perceptions of the environment in the public sector. Existing work concentrates

solely on the impact of archival objective measures of the organizational environment drawn from secondary data sources (Andrews et al., 2005). Third, the unit

of analysis is different service departments in multipurpose local governments,

making the results particularly generalizable as they apply to a wide variety of

public services.

To explore fully how public organizations can perceive and manage high levels of uncertainty, it is essential for researchers and policymakers to consider the

extent to which the linkages between PEU and internal characteristics proposed

by contingency theorists are susceptible to central and local discretion. In particular, how organizations should seek to align their strategy with the environmental

circumstances that they face is a critical question for public managers. Further

investigation of the relation between organizational fit and performance would

also provide important information on the policy levers that should be pulled to

maximize the impact of public sector reform. For example, the evidence presented

here supports the argument that the strategic management capability of public

organizations should be directed toward strengthening the fit between organizations and their external stakeholders (Poister & Streib, 1999).

There are, of course, some limitations of this analysis. The statistical results

may be a product of where and when the research was conducted. Therefore, it is

44 ppmr / September 2008 important to identify whether PEU differs in other organizational settings, both

within the United Kingdom and elsewhere and over other time periods. Welsh local governments operate within a highly regulated environment, which constrains

many aspects of their behavior (see Andrews et al., 2003). Public organizations

elsewhere across the globe may experience higher levels of PEU than those studied here. In addition, the ability to measure adequately perceived environmental

instability and unpredictability is limited by the use of a cross-sectional data set.

Because it was not possible to track changes in managers’ perceptions of the

environment, the analysis may be biased by the potential impact of recency on

managerial perceptions (Wholey & Brittain, 1989). Furthermore, debate abounds

about the direction of causality in the relation between PEU and organizational

characteristics (see, especially, Leifer & Huber, 1977). Longitudinal panel data

would enable the issue of causality between internal factors, such as strategy and

structure, and perceptions of environmental uncertainty to be traced with greater

precision.

Finally, the combined effect of management, organizational, and strategic factors

leaves a substantial part of the variation in PEU found here unexplained. This gap

may be partly attributable to limitations in the measures but may also be attributable to a host of additional individual and organizational level variables (such as

managerial experience, top team diversity, environmental scanning procedures,

and research and development capacity) that are beyond the scope of this study.

Similarly, the contribution of PEU to organizational outcomes could be explored

in greater depth, both by controlling for the management, organizational, and

strategic factors with which it is associated, and investigating its effect in combination with those factors. Nonetheless, the findings presented here have important

practical implications.

Decentralization of decision making by encouraging the participation of service managers in important strategic decisions can enable public organizations to

engage with the organizational environment in a manner conducive to the efficient

creation and transfer of client knowledge. For this decentralization to influence

service outcomes positively, other sources of organizational inertia must also

be overcome. Cross-departmental working within multipurpose organizations,

for instance, may corral vital information about the task environment (Willem

& Buelens, 2007). Another important way in which such knowledge about the

external environment can be communicated is through the use of citizen consultation techniques, such as neighborhood panels and public forums (Office of the

Deputy Prime Minister, 2006). However, managers should not be complacent

about the information that they gather from such exercises. For example, because

they often focus on specific issues and initiatives, consultation processes may

sometimes neglect broader issues of political responsiveness and social equity

(Yang & Holzer, 2006).

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 45

At a strategic level, PEU may be associated with two contradictory strategies:

prospecting and reacting. Prospecting implies a proactive attitude toward managing environmental change, and reacting signifies passive dependence on external

forces. Public organizations should, therefore, adopt a prospector strategy to

maximize the positive impact of managerial sensitivity to external circumstances.

Indeed, research suggests that prospecting organizations outperform their reacting

counterparts (Andrews, Boyne, & Walker, 2006). In addition, the positive relation between external political PEU and performance implies that more resources

should be devoted to ensuring that public managers understand their external

political environment. By learning more about the intricacies of the complex,

networked environments in which they increasingly operate, public managers

become better equipped to access vital exogenous sources of resources and support from other public, private, and nonprofit organizations, which, in turn, leads

to service improvement.

This study provides evidence on PEU in the public sector. Despite its limitations, the findings provide a strong platform for the application of the insights of

contingency theory to public organizations. Future research could furnish further

guidance for the theory and practice of public management by analyzing the linkages between PEU and the strategy, structure, and processes of organizations and

their separate and combined effects on public service performance.

References

Agranoff, R. (2005). Managing collaborative performance: Changing the boundaries of

the state? Public Performance & Management Review, 29(1), 18–45.

Aldrich, H.E. (1979). Organizations and environment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall.

Andrews, R., Boyne, G.A., & Walker, R.M. (2006). Strategy content and organizational

performance: An empirical analysis. Public Administration Review, 66(1), 52–63.

Andrews, R., Boyne, G.A., Law, J., & Walker, R.M. (2003). Myths, measures and modernisation: A comparative analysis of local authority performance in England and Wales.

Local Government Studies, 29(4), 54–78.

Andrews, R., Boyne, G.A., Law, J., & Walker, R.M. (2005). External constraints and public

sector performance: The case of comprehensive performance assessment in English

local government. Public Administration, 83(3), 639–656.

Armstrong, S.J., & Overton, T.S. (1977). Estimating non-response bias in mail surveys.

Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402.

Barnes, M., Newman, J., Knops, A., & Sullivan, H. (2003). Constituting “the public” in

public participation. Public Administration, 81(2), 379–399.

Begun, J.W., & Kaissi, A.A. (2004). Uncertainty in health care environments: Myth or

reality? Health Care Management Review, 29(1), 31–39.

Berman, E.M. (1997). Dealing with cynical citizens. Public Administration Review, 57(2),

105–112.

Bowerman, B.L., & O’Connell, R.T. (1990). Linear statistical models: An applied approach. 2d ed. Belmont, CA: Duxbury.

46 ppmr / September 2008 Boyd, B., Dess, G., & Rasheed, A. (1993). Divergence between archival and perceptual

measures of the environment: Causes and consequences. Academy of Management

Review, 18(2), 204–226.

Boyne, G.A. (2002). Public and private management: What’s the difference? Journal of

Management Studies, 39(1), 97–122.

Boyne, G.A. (2003). Sources of public service improvement: A critical review and research

agenda. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 13(2), 367–394.

Buchko, A. (1994). Conceptualisation and measurement of environmental uncertainty: An

assessment of the Miles and Snow perceived environmental uncertainty scale. Academy

of Management Journal, 37(2), 410–425.

Chandler, A. (1962). Strategy and structure: Chapters in the history of the industrial

enterprise. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Child, J. (1972). Organizational environment, structure and performance: The role of

strategic choice. Sociology, 6(1), 1–22.

Chun, Y.H., & Rainey, H.G. (2005). Goal ambiguity in U.S. federal agencies. Journal of

Public Administration Research and Theory, 15(1), 1–30.

Daft, R.L. (2001). Organizational theory and design. 7th ed. Cincinnati: Thomson

Learning.

Daft, R.L., Sormunen, J., & Parks, D. (1988). Chief executive scanning, environmental

characteristics, and company performance: An empirical study. Strategic Management

Journal, 9(2), 123–139.

Department of Environment, Transport, and Regions. (2000). Indices of multiple deprivation. London.

Dess, G.G., & Beard, D.W. (1984). Dimensions of organizational task environments.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 29(1), 52–73.

Dess, G.G., & Robinson, R.B., Jr. (1984). Measuring organizational performance in the

absence of objective measures: The case of the privately-held form and conglomerate

business unit. Strategic Management Journal, 5(3), 265–273.

Donaldson, L. (2001). The contingency theory of organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Doty, D.H., Bhattacharya, M., Wheatley, K.K., & Sutcliffe, K.M. (2006). Divergence between informant and archival measures of the environment: Real differences, artefact,

or perceptual error. Journal of Business Research, 59(2), 268–277.

Downey, H.K., & Slocum, J.W. (1975). Uncertainty: Measures, research, and sources of

variation. Academy of Management Journal, 18(3), 562–578.

Duncan, R. (1972). Characteristics of organizational environments and perceived uncertainty. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(3), 313–327.

Dutton, J.M. (1993). Interpretations on automatic: A different view of strategic issue

diagnosis. Journal of Management Studies, 30(3), 339–357.

Dutton, J.M., Fahey, L., & Narayanan, V.K. (1983). Toward understanding strategic issue

diagnosis. Strategic Management Journal, 4(4), 307–323.

Elkins, D.J., & Simeon, E.B. (1979). A cause in search of its effect, or what does political

culture explain? Comparative Politics, 11(1), 127–145.

Frumkin, P., & Galaskiewicz, J. (2004). Institutional isomorphism and public sector organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 14(3), 283–307.

Goerdel, H.T. (2006). Taking initiative: Proactive management and organizational performance in networked environments. Journal of Public Administration Research and

Theory, 16(3), 351–367.

Gomez-Mejia, L. (1992). Structure and process of diversification, compensation strategy,

and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 13(5), 381–397.

Grosskopf, S., & Yaisawamg, S. (1990). Economies of scope in the provision of local

public services. National Tax Journal, 43, 61–74.

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 47

Hage, J., & Aiken, M. (1967). Relationship of centralization to other structural properties.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 12(1), 72–93.

Harris, R.D. (2004). Organizational task environments: An evaluation of convergent and

discriminant validity. Journal of Management Studies, 41(5), 857–882.

Jencks, C., & Phillips, M. (Eds.). (1998). The black–white test score gap. Washington,

DC: Brookings Institution.

Jurkovich, R. (1974). A core typology of organizational environments. Administrative

Science Quarterly, 19(4), 380–394.

Katz, R. (1982). The effects of group longevity on project communication and performance.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 27(1), 81–104.

Ketchen, D.J., Jr., & Palmer, T.B. (1999). Strategic responses to poor organizational performance: A test of competing perspectives. Journal of Management, 25(5), 683–706.

Kitchener, M. (2000). The “bureaucratization” of professional roles: The case of clinical

directors in U.K. hospitals. Organization, 7(1), 129–154.

Lawrence, P., & Lorsch, J. (1969). Organization and environment. Homewood, IL: Irwin.

Leifer, R., & Huber, G.P. (1977). Relations among perceived environmental uncertainty,

organizational structure, and boundary-spanning behaviour. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 22(2), 235–247.

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services.

New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Long, J.S., & Ervin, L.H. (2000). Using heteroscedasticity consistent standard errors in

the linear regression model. American Statistician, 54(3), 217–224.

Maynard-Moody, S., Musheno, M., & Palumbo, D. (1990). Street-wise social policy: Resolving the dilemma of street-level influence and successful implementation. Western

Political Quarterly, 43(4), 833–848.

Meier, K.J., & Bohte, J. (2003). Not with a bang but a whimper: Explaining organizational

failures. Administration and Society, 35(1), 1–18.

Meier, K.J., & O’Toole, L.J. (2001). Managerial strategies and behaviour in networks:

A model with evidence from U.S. public education. Journal of Public Administration

Research and Theory, 11(3), 271–293.

Meier, K.J., & O’Toole, L.J. (2003). Public management and educational performance: The

impact of managerial networking. Public Administration Review, 63(6), 689–699.

Mellahi, K., Jackson, P., & Sparks, L. (2002). An exploratory study into failure in successful organizations: The case of Marks and Spencer. British Journal of Management,

13(1), 15–30.

Meyer, A.D. (1982). Adapting to environmental jolts. Administrative Science Quarterly,

27(4), 515–538.

Miles, R., & Snow, C. (1978). Organizational strategy, structure and process. London:

McGraw Hill.

Milliken, F. (1987). Three types of perceived uncertainty about the environment: State,

effect and response uncertainty. Academy of Management Review, 12(1), 133–143.

National Assembly for Wales. (2003). National Assembly for Wales performance indicators 2001–2002. Cardiff.

National Assembly for Wales. (2004). National Assembly for Wales performance indicators 2002–2003. Cardiff.

Nunnally, J.C. (1978). Psychometric theory. 2d ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. (2003). Equality and diversity in local government:

A literature review. London.

Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. (2006). Promoting effective citizenship and community empowerment: A guide for local authorities on enhancing capacity for public

participation. London.

48 ppmr / September 2008 Office for National Statistics. (2003). Census 2001: Key statistics for local authorities.

London: TSO.

Office of Public Services Reform. (2002). Reforming our public services. Principles into

practice. London: Cabinet Office.

O’Toole, L.J., Jr., & Meier, K.J. (1999). Modelling the impact of public management:

Implications of structural context. Journal of Public Administration Research and

Theory, 9(4), 505–526.

Ozsomer, A., Calantone, R., & Di Benedetto, A. (1997). What makes firms more innovative?

A look at organizational and environmental factors. Journal of Business and Industrial

Marketing, 12(6), 400–416.

Parker, D., & Hartley, K. (2003). Transaction costs, relational contracting and public

private partnerships: A case study of U.K. defence. Journal of Purchasing and Supply

Management, 9(3), 97–108.

Poister, G.D., & Streib, G.D. (1999). Strategic management in the public sector: Concepts,

models and processes. Public Productivity & Management Review, 22(3), 308–325.

Quinn, R.E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1981). A competing values approach to organizational effectiveness. Public Productivity Review, 5(2), 122–140.

Rainey, H.G. (1997). Understanding and managing public organizations. 2d ed. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Rainey, H.G., & Steinbauer, P. (1999). Galloping elephants: Developing elements of a

theory of effective government organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research

and Theory, 9(1), 1–32.

Russell, R., & Russell, C. (1992). An examination of the effects of organizational norms,

organizational structure, and environmental uncertainty on entrepreneurial strategy.

Journal of Management, 18(1), 639–657.

Simon, H.A. (1976). Administrative behavior: A study of decision-making processes in

administrative organization. 3d ed. London: Macmillan.

Snow, C.C., & Hrebiniak, L.G. (1980). Strategy, distinctive competence, and organizational

performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(2), 317–336.

Starbuck, W.H. (1976). Organizations and their environments. In M.D. Dunnette (Ed.),

Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1069–1123). Chicago:

Rand McNally.

Staw, B., Sandelands, L., & Dutton, J. (1981). Threat-rigidity cycles in organizational

behavior: A multi-level analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26(4), 501–524.

Stevens, J.M., & McGowan, R.P. (1983). Managerial strategies in municipal government

organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 26(3), 527–534.

Stigler, G. (1958). The economics of scale. Journal of Law and Economics, 1, 54–71.

Swindell, D., & Kelly, J.M. (2000). Linking citizen satisfaction data to performance measures:

A preliminary evaluation. Public Performance & Management Review, 24(1), 30–52.

Terreberry, S. (1968). The evolution of organizational environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 12(3), 377–396.

Tosi, H., Aldag, R., & Storey, R. (1973). On the measurement of the environment: An

assessment of the Lawrence and Lorsch environmental uncertainty subscale. Administrative Science Quarterly, 18(1), 27–36.

Walker, R.M., & Enticott, G. (2004). Using multiple informants in public administration:

Revisiting the managerial values and actions debate. Journal of Public Administration

Research and Theory, 14(3), 417–434.

Weick, K.E. (1969). The social psychology of organizing. Reading, MA: AddisonWesley.

Wholey, D.R., & Brittain, J. (1989). Characterizing environmental variation. Academy of

Management Journal, 32(4), 867–882.

Andrews / Perceived Environmental Uncertainty 49

Willem, A., & Buelens, M. (2007). Knowledge sharing in public sector organizations: The

effect of organizational characteristics on interdepartmental knowledge sharing. Journal

of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17(4), 581–606.

Williams, C. (2003). Developing community involvement: Contrasting local and regional

participatory cultures in Britain and their implications for policy. Regional Studies,

37(5), 531–541.

Yang, K.F., & Callahan, K. (2005). Assessing citizen involvement efforts by local governments. Administration & Society, 29(2), 191–216.

Yang, K.F., & Holzer, M. (2006). The performance-trust link: Implications for performance

measurement. Public Administration Review, 66(1), 114–126.

Zhang, J., & Dawes, S. (2006). Expectations and perceptions of benefits, barriers, and

success in public sector knowledge networks. Public Performance & Management

Review, 29(4), 433–466.

Dr. Rhys Andrews is a research fellow at the Centre for Local and Regional Government Research at Cardiff University. His research interests focus on civic culture,

organizational environments, and public service performance. His publications

include articles in the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory and

Public Administration Review.

50 ppmr / September 2008 Appendix. National Assembly for Wales Performance Indicators (NAWPI)

Effectiveness and Expenditure Measures 2001–2003

Service area

Education

Social

services

Housing

Effectiveness NAWPI

Expenditure NAWPI

• Net expenditure per nursery and

primary pupil under 5

• Net expenditure per primary pupil

age 5 and over

• Net expenditure per secondary

pupil under 16

• Net expenditure per pupil secondary pupil age 16 & over

• Average General Certificate in

Secondary Education (GCSE) or

General National Vocational

Qualification (GNVQ) points

score of 15/16-year-olds

• % 15/16-year-olds achieving 5 or

more GCSEs at grades A*–C or

the vocational equivalent

• % 15/16-year-olds achieving one

or more GCSEs at grade G or

above or the vocational equivalent

• % 11-year-olds achieving Level 4

in Key Stage 2 Maths

• % 11-year-olds achieving Level 4

in Key Stage 2 English

• % 11-year-olds achieving Level 4

in Key Stage 2 Science

• % 14-year-olds achieving Level 5

in Key Stage 3 Maths

• % 14-year-olds achieving Level 5

in Key Stage 3 English

• % 14-year-olds achieving Level 5

in Key Stage 3 Science

• % 15/16-year-olds achieving at

least grade C in GCSE English or

Welsh, Mathematics, and Science

in combination

• % 15/16-year-olds leaving fulltime education without a recognized qualification (inverted)

• Cost of children’s services per

• Percentage of young people

child looked after

leaving care age 16 or over with

at least 1 GCSE at grades A*–G

or GNVQ

• Proportion of rent collected

• Average weekly management costs

• Rent arrears of current tenants

• Average weekly repair costs

(inverted)

• Rent written off as not collectable

(inverted)