Paper - Teaching and Learning Research Programme

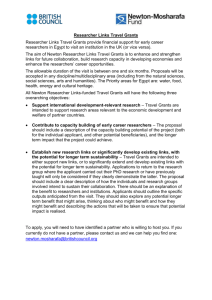

advertisement