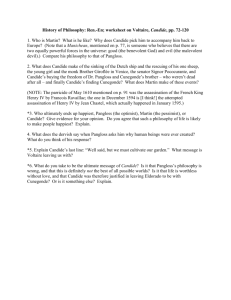

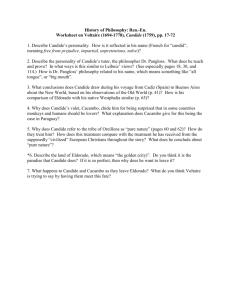

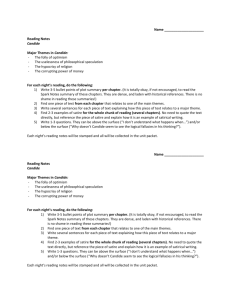

Candide

advertisement