Producing and Procuring Horticultural Crops with Chinese

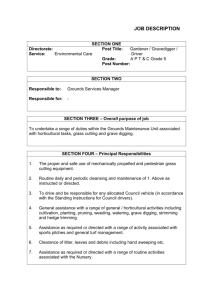

advertisement