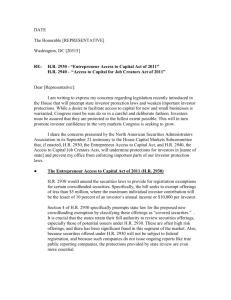

Structuring Best Efforts Offerings and Closings Under Rule 10b-9

advertisement