badadey2006 - UWSpace Home

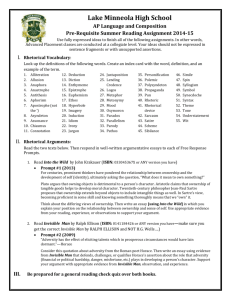

advertisement