Removing the Roadblocks - UCLA/IDEA | Institute for Democracy

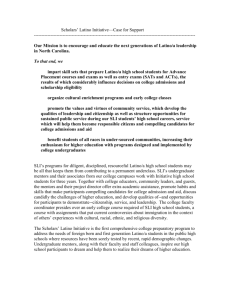

advertisement