Chapter 2 Literature Review

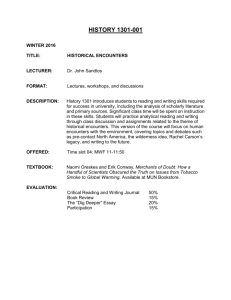

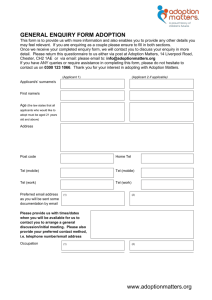

advertisement