Why Does an Organization Choose OneType of Gainsharing Plan

advertisement

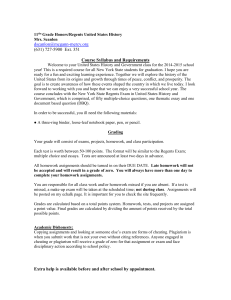

AICG WORKING PAPER 2003-10 WHY DOES AN ORGANIZATION CHOOSE ONE TYPE OF GAINSHARING PLAN OVER ANOTHER? A CONGRUENCE PERSPECTIVE Dong-One Kim Associate Professor Korea University College of Business Administration Anam-dong, Sungbuk-gu Seoul, South Korea 136-701 Tel.: (02)3290-1949 Fax: (02)3290-2526 e-mail: dokim@korea.ac.kr WHY DOES AN ORGANIZATION CHOOSE ONE TYPE OF GAINSHARING PLAN OVER ANOTHER? A CONGRUENCE PERSPECTIVE Dong-One Kim Associate Professor Korea University College of Business Administration Anam-dong, Sungbuk-gu Seoul, South Korea 136-701 Tel.: (02)3290-1949 Fax: (02)3290-2526 e-mail: dokim@korea.ac.kr August 2002 The author wishes to thank Paula Voos, Kenneth Mericle, Anne Miner, and John Lund for their invaluable input and comments. 3 BIOGRAPHY Dong-One Kim is Associate Professor of Employment Relations at Korea University, Seoul, Korea. He received a Ph.D. degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Prior to joining the faculty of Korea University in 1997, he was on the faculty of the School of Business at the State University of New York at Oswego. His research interests are workplace innovations, employee involvement, and comparative employment relations. His articles have been published in Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Industrial Relations, Industrial Relations/Relations Industrielles, Advances in Industrial and Labor Relations, Human Resource Management Handbook, and Journal of Applied Behavioral Sciences. 4 ABSTRACT Utilizing multinomial logit analyses of survey data from 217 organizations with experience of gainsharing plans in North America, congruence explanations of the choice of a particular type of gainsharing plan were examined. The choice of a particular type of gainsharing plan was found to be influenced by situational factors such as labor intensity, organizational size, and nonmanufacturing. Program goals such as reducing nonlabor costs and improving labor relations were also related to the probability of program adoption. Theoretical and managerial implications are discussed. 5 Introduction As gainsharing programs, such as the Scanlon, Multicost Scanlon, Rucker, and Improshare plans, have been increasingly adopted by American corporations in the last decade, several studies have examined the effect of gainsharing on organizational outcomes (Hatcher & Ross, 1991; Kaufman, 1992), the factors influencing such outcomes (Bullock & Tubbs, 1990; Cooper, Dyck, & Frohlich, 1992; Gowen & Jennnings, 1991; Kim, 1996; Kim & Voos, 1997), and the survival of gainsharing programs (Kim, 1999). There has, however, been very little empirical research on what makes an organization more likely to choose one particular type of gainsharing plan over another. Although there is some evidence that the choice of gainsharing plan is related to program success (Kim, 1996), previous literature has generally been silent on this issue. When implementing a gainsharing program, formula determination is the leading cause of disagreement among corporate officials, local management, human resource management, union representatives, and outside consultants (Bazerman & Graham-Moore, 1983; GrahamMoore, 1990). Indeed, one long-term observer has argued that “the one-third of gainsharing installations that failed did so in the first year.... typically, the blame is placed on the formula” (Graham-Moore, 1990, p. 49). Clearly, human resource management (HRM) practitioners need to be aware of the patterns of program adoption and the reasons for those patterns so as to be able to better select the plan that would be appropriate for their organization. The purpose of this study is to identify factors systematically associated with the choice of a particular gainsharing plan once an organization has decided to adopt gainsharing. Various hypotheses were developed from a congruence perspective to explain the design of gainsharing programs. While previous theoretical models explain the design of various pay 6 systems, such as the agency, transaction cost, resource dependence, and institutional models (see Barringer & Milkovich, 1998 for details), they do not fully explain the design of gainsharing plans. The first three models (i.e., the agency, transaction cost, and resource dependence models) mainly address the efficiency merit of a particular type of innovation, while the last model (i.e., the institutional model) describes how institutional pressures influence the design of an innovation. None of these models, however, deals with interactions between design features, and program goals and situational conditions. Although these dimensions are among the most important factors that gainsharing consultants pay attention to in the process of designing a gainsharing plan, I found that most existing theoretical models do not incorporate these issues in their frameworks. This was one of the reasons why I planned this research. Thus, the present study focuses on an alternative perspective – the congruence approach – in explaining the design of gainsharing programs. I examined survey data from 217 organizations with actual experience of gainsharing plans in the U.S. and Canada. To test the congruence explanations, I used a multinomial logit model to capture the choice between five major types of gainsharing: the Simple Scanlon, Multicost Scanlon, Rucker, Improshare, and customized plans. Types of Gainsharing Gainsharing typically involves a contingent group compensation scheme combined with an employee involvement (EI) component. With gainsharing, each member of a gainsharing group receives a bonus based on the output of the group as a whole, as opposed to one based on the employee’s individual output. Whereas profit-sharing provides employees with a companywide bonus based on some percentage of company profits or profits beyond some fixed 7 minimum, gainsharing can be implemented on an establishment or departmental basis, and employees are generally paid a portion of the savings generated when costs fall below a predetermined level. Gainsharing can also be implemented for companies as a whole. Gainsharing programs can be classified into five major categories, depending mainly on how bonuses are calculated. Simple Scanlon plans are based on labor-cost ratios, Multicost Scanlon plans on production-cost ratios, Rucker plans on value-added ratios, and Improshare plans on unit-per-hour ratios. Customized plans, on the other hand, use formulae tailored to the specific needs of individual organizations, often taking into account other factors besides the efficiency of labor (such as quality, safety, customer satisfaction, attendance records, and ontime delivery records). The attributes of the major types of gainsharing programs are listed in Table I. Some plans are considerably more complex to administer than others and require more information and/or administrative expertise: in general, Simple Scanlon plans require the least information, Rucker plans require somewhat more information, Multicost Scanlon plans require even more, and Improshare plans require even greater organizational information and expertise. Some plans put more emphasis on reducing labor costs (Simple Scanlon and Improshare plans), whereas others emphasize reducing other costs (Multicost Scanlon and Rucker plans), and still others (customized plans) have even more complex goals. Some put a greater emphasis on formal employee involvement and employee votes (Scanlon plans in general) and others may or may not have a formal involvement component (Improshare plans typically place the least emphasis on employee involvement). The various types of plans also differ in the way gains are split between labor and management, with Scanlon Plans generally providing a greater proportion of gains to 8 employees. Theoretical Issues and Hypotheses Previous Theoretical Models A few theoretical models can be identified in the previous literature explaining the adoption and diffusion of HRM programs. For example, Williamson (1981) argues that management’s decisions about pensions might be related to transaction costs. Pfeffer and DavisBlake (1987) apply resource dependence theory in explaining compensation systems for university administrators. Goodstein (1994), and Ingram and Simons (1995) provide institutional and resource dependence models in analyzing the adoption of work family programs. Eisenhardt (1988) utilizes agency and institutional models to explain the adoption of various pay systems for salespeople. Barringer and Milkovich (1998), explaining the adoption of various flexible benefit programs, provide a comprehensive theoretical discussion and formulate four theoretical lenses: the agency, transaction cost, resource dependence, and institutional models. The main thesis of the first three models is that the purpose of program design is to maximize the efficiency potentials of the program. Thus, all four models can be reclassified into two groups: efficiency (including the agency, transaction cost, and resource dependence models) and institutional models. The efficiency models assume that organizations actively manage environmental constraints by adopting organizational structures or programs that ensure the efficient flow of resources and minimize costs. Specifically, agency cost theorists argue that the “classical capitalist firm” is established in order to circumvent the free-riding problem by assigning the task of monitoring to a specialist whose incentive to monitor is his/her claim to the team’s “residual” 9 income. That is, if the monitor is to receive any residual profits above prescribed amounts, he/she will have a strong incentive not to shirk his/her duty as a monitor (Alchian & Demsetz, 1972). The obvious agency costs are those associated with the reduced incentives for the user to maintain the asset properly and to guard it from theft, and the increased incentives to misuse it (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). The agency theory implies that human resource programs should be designed to motivate employees to act in the best interests of the principal (Kim & Voos, 1997). Based on economic reasoning, transaction cost theorists argue that organizations establish structures that minimize the costs of their transactions with employees when the employees’ potential for opportunistic behavior is high. That is, where organizational-specific skills are critical to the organization, turnover can be costly, and organizations adopt internal governance structures to minimize the transaction costs incurred in the negotiation process (Williamson, 1975). According to this view, organizations tend to adopt HRM structures that can stabilize employment and provide incentives for employees to act in the organizations’ interests (Williamson, 1981). The resource dependence model assumes that managerial decisions are influenced by internal and external agents who control and distribute critical resources such as funds, personnel, or both (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). These agents can explicitly or implicitly exert pressure on an organization to adopt certain innovations or structures by linking compliance with resource allocation. Thus, organizational structures and HRM systems tend to be shaped by agents who control critical resources. Whereas the resource dependence model, in particular that part of it concerning external pressures, is very similar to the institutional model’s “coercive pressures” (which will be discussed next), the resource dependence model assumes to a greater extent than 0 1 does the institutional model that organizations respond strategically and autonomously to external pressures (Barringer & Milkovich, 1998). Hence, the primary consideration behind management decisions from these perspectives is expected efficiency gains. The institutional model assumes that organizations do not exercise active choice; rather, they passively conform to environments. Organizations theoretically adopt structures that enhance their legitimacy in the external environments, regardless of the impact on the technical efficiency of internal operations. According to this view, organizations adopt a particular type of innovation through three isomorphic processes: coercive, mimetic, and/or normative isomorphism. Thus, institutional pressures and modeling behaviors are the primary factor influencing management decisions about innovations (Barringer & Milkovich, 1998). The common theme of the above four models is the attention they give to human factors. The first two models (the agency and transaction cost models) mainly deal with how to manage human resources within an organization, whereas the latter two models (the resource dependence and institutional models) focus in general on the issue of how to satisfy powerful outside agencies or gain legitimacy in the eyes of outsiders. Interestingly, all these models ignore the influence of environments and situations faced by organizations, and the goal of program implementation. Thus, they do not seem to explain factors that are actually considered by gainsharing practitioners and consultants in the design process. Congruence Hypothesis The present study hypothesizes that organizations naturally choose a program which fits with program goals and situational conditions. Organizations are expected to design a program which is consistent with the goal of the program as long as they have unambiguous goals. 1 1 Organizations are also expected to adopt practices that compliment existing environmental constraints because this type of congruence enhances the efficiency gain by maximizing synergy effects with existing components of the organization. Even though one may not be sure that the congruent system enhances organizational efficiency, it is obvious that a program that is inconsistent with program goals and situational factors will not accomplish the intended objectives. If the design features of the program do not match program goals, situational factors, or both, the program is unlikely to be fully implemented, effectively operated, and persist over time. Indeed, the previous literature indicates that the unique design aspects of an organizational development program themselves may contribute to its survival or discontinuation. Throughout the life of a gainsharing program, the strengths and weaknesses of each program interact with organizational goals and strategies, and situational and environmental factors. During this process, some design features may facilitate the long-term viability of the program, while others may contribute to program failure (Kim, 1999). Therefore, in order to improve the efficiency gains and longevity of a gainsharing program, organizations should design a gainsharing program that is consistent with the program goals and situational conditions. Other studies implicitly and explicitly assume the influence of congruence (in terms of situational factors or program goals) in program adoption. For example, Lawler (1988) argues that organizations must choose an employee involvement program that is congruent with existing situational factors such as the nature of the work and technology, the values and goals of the organization, and the organization’s current management approach. Osterman (1994) also found that firms considering employee commitment as an important goal are less likely to use 2 1 temporary employees and more likely to invest in innovative work practices such as skills training and incentive compensation. The congruence approach in the present study is different from the internal fit and external fit approaches found in strategic HRM literature (Arthur, 1994; Huselid, 1995). Internal fit refers to the tendency for firms to adopt HRM practices that complement and support each other, whereas external fit suggests that firms match HRM practices with competitive strategies. The congruence model, which addresses the relationship between an HRM program and its immediate goal, is narrower than the external fit concept. On the other hand, the concept of the congruence model, which stresses the congruence between an HRM program and its technical environments, is broader than that of internal fit. The congruence hypothesis is similar to the efficiency models (i.e., the agency, transaction cost, and resource dependence models) because it basically tries to improve efficiency. Thus, the congruence model can be considered another type of efficiency model. The present theoretical framework should be considered as a complementary model to the existing four theoretical models because it does not deny the existing models. In the following, the seven congruence hypotheses will be discussed in turn. The situational conditions of the congruence model considered in the present study include labor intensity, organizational size, and industry type. Labor Intensity. Labor-intensive organizations are expected to be more interested in the efficient use of the labor force, other things being equal, because the saving of labor costs is so important in these organizations. Thus, labor-intensive organizations are more likely to adopt plans emphasizing the saving of labor costs, and less likely to adopt plans focusing on other 3 1 goals (e.g., the saving of material cost and overhead, and quality improvement), other things being equal. For this reason, it was hypothesized that labor-intensive organizations are more likely to choose the Simple Scanlon or Improshare plans over the Multicost Scanlon plan because these plans put the greatest emphasis on reducing labor costs. In general, customized plans put the least emphasis on reducing labor costs. Thus, I hypothesize that they are least likely to be chosen by labor-intensive organizations. Hypothesis 1: Labor-intensive organizations are more likely to choose labor-cost focused plans (i.e., the Simple Scanlon or Improshare plans) than other plans (i.e., the Multicost Scanlon plan and customized plans). Organization Size. Gainsharing plans differ in terms of the administrative complexity. The choice of gainsharing plan is constrained by the organization’s ability to produce various data in a timely fashion and maintain an appropriate management system. I hypothesized that differences in administrative difficulty among various gainsharing plans affected adoption probabilities. The administration of the Simple Scanlon plan is relatively easy: only basic accounting skills for dealing with payroll data and production data are needed. The administration of the Rucker plan requires some accounting expertise and a cost accounting system which can provide payroll data, production data, and the costs of outside supplies. The Multicost Scanlon plan is more complicated than the Simple Scanlon or Rucker plans as it requires an accounting system that provides a wider variety of data (e.g., data concerning payroll, sales, revenues, inventory, material cost, overhead, and other costs) on a monthly basis. The administration of the 4 1 Improshare plan requires industrial engineering expertise as well as cost accounting. The need for detailed time standards probably requires the most sophisticated management information system of any of the standardized plans. Although customized plans are good at incorporating diverse business strategies into the gainsharing bonus formula, they are generally more difficult to develop than standard plans. There is accumulated knowledge regarding how to operate a standard gainsharing plan – for instance, how to measure and evaluate group performance (see, for example, Bazerman & Graham-Moore, 1983; Moore & Ross, 1978; Ross & Ross, 1990). In contrast, the development and installation of a customized plan requires considerable design work, trial and error, administrative tasks, expertise in accounting and work systems, and a sophisticated management information system that can generate different types of data sets from those related to standard programs. In the present study, the size of the organization was considered as a proxy of the organization’s capacity to implement and administer gainsharing plans. Such a capacity may include the ability to deal with administrative complexity, the availability of specialized full-time personnel to manage the program, and the ability of the management information system to provide various data on time. Small organizations, which usually do not possess such a capacity to implement and administer more complex programs (even with the help of consultants), are more likely to rely more on administratively simpler plans (e.g., the Simple Scanlon and Rucker plans). On the other hand, large organizations will not have such constraints and should be able to manage gainsharing plans requiring more administrative complexity and a more sophisticated management information system (e.g., the Multicost Scanlon, Improshare, and customized plans). 5 1 For this reason, I hypothesize that small organizations are more likely to choose the Simple Scanlon or Rucker plans over the Multicost Scanlon, Improshare, or customized plans. Hypothesis 2: Small organizations are more likely to prefer administratively simpler plans (i.e., the Simple Scanlon or Rucker plans) to more complex plans (i.e., the Multicost Scanlon, Improshare, or customized plans). Industry Differences. Although gainsharing originated in, and has been traditionally used in, manufacturing,1 it has recently spread to nonmanufacturing: to mining, communications, retail, financial services, hospitals, and even government sectors (e.g., Markham, Scott, & Little, 1992; Jarrett, 1990; Ross, 1990). While nonmanufacturing organizations can use both standard and customized plans, some standard plans are more difficult than others to apply to nonmanufacturing settings. Specifically, the Improshare plan is based on the use of detailed work measures for each task. Because detailed time standards must be available to implement the Improshare plan, it tends to be more applicable to quasi-manufacturing service operations, such as large-scale laundries (e.g., hospital laundries) and information-processing operations, where operation is not interrupted by customer contacts of unpredictable length (Ross, 1990). It can be difficult to apply the Improshare plan to typical nonmanufacturing settings where it is hard to establish a baseline time standard due to unpredictable customer contacts. Other standard gainsharing plans (e.g., the Simple Scanlon, Multicost Scanlon, and Rucker plans) are relatively easy to implement in a variety of nonmanufacturing settings since these plans use a dollar-based measure, as opposed to a time-based one. For this reason, I hypothesize that nonmanufacturing organizations are less likely to choose the Improshare plan 6 1 than other gainsharing plans. Hypothesis 3: Nonmanufacturing organizations are less likely to prefer the Improshare plan to other gainsharing plans. The most popular goals that organizations pursue when implementing gainsharing include: improvement of labor productivity, reduction of nonlabor costs, improvement of quality, and improvement of labor relations (for some examples of this, see Cotton [1993], Schuster [1984], and Gowen [1991]). I expected that organizations with different goals would choose different plans, other things being equal, given that different plans emphasize particular outcomes. For example, consider two organizations with a similarly high degree of labor intensity. For the economic reasons just discussed, both organizations should be more likely to choose those gainsharing plans that focus on reducing labor costs. However, if one of the two organizations has the explicit goal of improving product quality (and the other does not), that should additionally influence the relative probabilities of plan selection. It is in this sense that I tested whether or not conscious organizational goals were important factors in plan selection. Goal: Improving Labor Productivity. Whereas the Simple Scanlon and Improshare plans focus primarily on improving labor productivity, the Multicost Scanlon plan (and Rucker plan, to a lesser degree) aims to save nonlabor costs as well as labor costs. Customized plans generally emphasize objectives other than labor productivity (such as quality, safety, customer satisfaction, attendance records, or on-time delivery records). Consequently, organizations seeking to improve labor productivity by using gainsharing are more likely to choose the Simple Scanlon and Improshare plans than the Multicost Scanlon, customized, or Rucker plans. Hypothesis 4: Organizations seeking to improve labor productivity by using gainsharing 7 1 are more likely to choose the Simple Scanlon and Improshare plans than the Multicost Scanlon, customized, or Rucker plans. Goal: Reducing Nonlabor Costs. On the other hand, if the reduction of nonlabor costs is an important goal when implementing gainsharing, the Multicost Scanlon plan is a clear choice since it includes most nonlabor costs as well as labor costs in the formula. Alternatively, some organizations may consider customized plans because some customized plans focus heavily on nonlabor savings, such as reduction in waste, energy consumption, and overhead costs. Thus, I expect that organizations trying to reduce nonlabor costs are more likely to prefer the Multicost Scanlon or customized plans (or the Rucker plan, to a lesser degree) to the Simple Scanlon or Improshare plans. Hypothesis 5: Organizations trying to reduce nonlabor costs by using gainsharing are more likely to choose the Multicost Scanlon or customized plans than the Simple Scanlon or Improshare plans. Goal: Improving Quality. Although some customized plans include the measure of product (or service) quality in the gainsharing formula, standard plans usually do not. Indeed, the pursuit of improved labor productivity or cost reduction in standard plans sometimes conflicts with quality improvement. Consequently, I hypothesize that if the improvement of quality is an important goal when implementing gainsharing, organizations are more likely to choose customized plans over standard plans. Hypothesis 6: Organizations trying to improve quality by using gainsharing are more likely to choose customized plans over other, standard plans. Goal: Improving Labor Relations. Whereas some plans heavily emphasize a cooperative 8 1 labor-management relationship, others do not. The Scanlon plan has been a symbol of labormanagement cooperation in North America. It has been argued that the key to the Scanlon plan’s success is not the particular calculation, but rather the spirit of labor-management cooperation, such as congruence of management and employee objectives, and their commitment to the success of the plan (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1981). Other plans do not emphasize this element to the same extent. Consequently, if the improvement of labor relations is an important goal when implementing gainsharing, organizations should be more likely to prefer Scanlon-type plans (e.g., the Simple Scanlon or Multicost Scanlon plans) to other plans (e.g., the Rucker, Improshare, or customized plans). Hypothesis 7: Organizations trying to improve labor relations by using gainsharing are more likely to choose Scanlon-type plans (e.g., the Simple Scanlon or Multicost Scanlon plans) than other plans. Control Variables In the present study, I include several control variables that may account for some variance in the adoption behavior of a particular gainsharing program. These are: unionization, the existence of a consultant, and a periodic and regional fad. Unions. Managerial decisions regarding program choice are expected to be influenced by union preference because labor unions control human resources at the workplace and can exert their influence through collective action such as strikes. Indeed, the formula determination is the major cause of disagreement among management and union (Bazerman & Graham-Moore, 1983; Graham-Moore, 1990), and union opposition to gainsharing has been found to be negatively related to program success (Kim, 1996). 9 1 I hypothesize that unionized organizations are more likely to choose Scanlon-type plans (e.g., the Simple Scanlon or Multicost Scanlon plans) than non-Scanlon plans (e.g., the Rucker, Improshare, or customized plans) for the following reasons. First, the Scanlon plan was originally developed and popularized by union leaders (e.g., Joseph Scanlon and Frederick Lesieur), while other plans were developed by accountants (e.g., Allan W. Rucker) or industrial engineers (e.g., Mitchell Fein). Consequently, many well-known early Scanlon plans were implemented in unionized organizations (e.g., Empire Steel and LaPointe Machine Tool). Second, Scanlon plans typically direct a larger portion of the bonus pool (75%) to workers than do Rucker or Improshare plans (50%). This appeals to union leaders. For these reasons, it is expected that unionized organizations are more likely to choose Scanlon-type plans than nonScanlon plans. Hypothesis 8: Unionized organizations are more likely to choose Scanlon-type plans than non-Scanlon plans. Consultants. While it is possible to develop gainsharing programs without outside help, many organizations rely on consultants. Outside consultants can provide expertise in program design, and their recommendations are often taken seriously by organizations. How does consultant involvement influence program choice? Although some consultants commonly install customized plans, they are exceptions. Most consultants in North America specialize in specific plans or copyrighted standard plans. One reason for this tendency may be the need for consultants to reduce design and installation costs by adopting well-structured standard plans. In a similar vein, Abrahamson (1991) indicates that fashion-setting organizations such as consulting firms may select only those innovations they believe they can market profitably, regardless of 0 2 how technically efficient the technologies would be for organizations. In fact, the Rucker and Improshare plans are copyrighted ones. The development of customized plans usually requires internal expertise. For this reason, I expect that organizations with outside consultant involvement in the design process are more likely to choose standardized plans than customized plans. Hypothesis 9: Organizations with outside consultant involvement in the design process are more likely to choose standardized plans than customized plans. Periodic and Regional Fads. Although gainsharing has existed in North America for nearly 100 years in a variety of forms, the interest in these programs increased considerably in the 1980s. Before the mid-1980s, gainsharing was primarily adopted by “progressive” companies that had an unusual interest in a participative management model. The rising popularity of gainsharing in the mid-1980s meant that “normal” companies increasingly introduced gainsharing during that period along with other popular employee involvement programs. I expect that these “normal” companies will show different patterns of program choice from the earlier “progressive” companies. Organizations also imitate other organizations that are proximate either geographically or in terms of their communication network (Abrahamson, 1991). Thus, it is believed that there are regional/national influences on program choice (i.e., Northcentral states, the Northeast, the South, the West, and Canada). These regional/national variables may reflect the influence of “model” companies with respect to gainsharing practices in that area, or a common managerial network in particular areas.2 Although I did not formulate any specific hypotheses about periodic and regional fads, I expect that there will be different patterns of program choice between early and 1 2 late adopters of gainsharing, and among organizations located in different regions. Research Methods Survey Methods I tried to obtain as large a sample as possible by investigating several different sources. A probability sampling technique, although preferable, seemed unrealistic since there was no existing database on gainsharing programs. Thus, I had to rely on a nonprobability sampling method and later determine whether or not it was reasonably representative. I judged it to be quite representative in crucial respects. Starting in March 1992, I contacted: (1) consulting firms dealing with gainsharing programs; (2) researchers who had carried out surveys related to gainsharing programs and published their results in journals; (3) union officials or plant managerial employees who attended labor education programs on gainsharing; and (4) regional or national offices of international unions. In addition, I examined (5) publications of the U.S. Department of Labor dealing with work innovation to identify organizations with gainsharing experience. The above sampling method provided a list of 622 organizations in the U.S. and Canada that either had experience of a gainsharing program in the past, or currently had a gainsharing program. The survey was sent to the industrial relations or human resource manager who was responsible for operating the gainsharing program. The respondents were told that their answers would be kept confidential. Of the 622 surveys initially sent in June 1992, 50 were returned uncompleted – for example, because the organization had moved or closed. Among the 572 organizations that were successfully contacted, 334 surveys (58.4%) were eventually completed or partially completed, 2 2 and returned (a response rate achieved through the use of three survey waves and the deletion of respondents after each wave). After deleting cases in which there were missing data on any of the variables in the model, 217 remained in the sample. Representativeness of the Sample Since nonprobability sampling methods were used in the present study, the representativeness of the sample had to be evaluated. Previous surveys of gainsharing provided some clues to the representativeness of this sample. First, Kaufman (1992) found that 23.2% of organizations in his sample that implemented the Improshare plan eventually discontinued it, while Fein (cited in Kaufman, 1992) estimates that 15-20% of Improshare programs are discontinued. It was found that 21.4% of gainsharing programs in the present sample were discontinued. Second, Globerson and Parsons (1988) found that 53% of 92 companies implementing Improshare programs were unionized. In the present sample, 52% of the organizations with gainsharing experience were found to be unionized. In addition, the present sample can be compared with two previous surveys carried out by Markham, Scott, and Little (1992), and O’Dell and McAdams (1987).3 Markham, Scott, and Little (1992) found the ratio between the number of active Improshare plans and that of Scanlon plans to be 0.90. O’Dell and McAdams (1987) found the ratio between the number of Improshare plans and that of Scanlon plans to be 1.40. In the present sample, the ratio of Improshare plans to Scanlon plans was 1.21. The comparison suggests that compared with the previous surveys, the Scanlon and Improshare plans were not seriously overrepresented or underrepresented in our sample. In sum, the above comparisons suggest that although our sample was not random, it was 3 2 reasonably representative in some major respects.4 Measurement The variables used in this study were measured by questions in the mail survey. Five mutually exclusive categorical (0-1) variables were constructed from this data using information from the respondents about the bonus formula used. The respondents were asked to choose the closest performance measure of the gainsharing program among five categories. If the respondents chose the ratio of payroll costs to sales value of production as the performance measure, the gainsharing program was considered to be a Simple Scanlon plan. If the ratio of payroll, material, and overhead to sales value of production was used, it was considered to be a Multicost Scanlon plan. If the ratio of payroll costs to value added was used, it was considered to be a Rucker plan. Programs using the ratio of actual labor hours to standard labor hours were considered to be Improshare plans. Programs using other measures were considered to be customized plans. If the respondents stated that the work system was (heavily) labor intensive, the variable labor intensity was coded 1. If they stated that the work system was (heavily) capital intensive, it was coded 0. If an organization had less than 100 employees, the variable, small organization, was coded 1 (otherwise, 0). The respondents were asked either to provide the SIC code of the primary product (or service) of the organization, or to describe it. If an organization belonged to the service, retail trade, transportation, mining, or construction industries, nonmanufacturing was coded 1 (otherwise, 0). The variables measuring the goals in adopting gainsharing were created from questions regarding the relative importance of the following four objectives of the gainsharing program: 4 2 improving labor productivity, reducing nonlabor costs, improving product (service) quality, and improving labor relations. A response of “very important” on a three-point scale led to the coding of that goal as present. It should be noted that the four categories were not mutually exclusive since some respondents considered more than one objective to be very important. If an organization was unionized, the variable, union, was coded 1 (otherwise, 0). If an outside consultant was involved in designing the gainsharing program, consultant involvement was coded 1 (otherwise, 0). If a gainsharing program was begun in or after 1986, the variable, since 1986, was coded 1; if a program was begun before 1986, it was coded 0. Four regional/national 0-1 variables were constructed: the Northeast, the South, the West, and Canada (the benchmarking category was Northcentral states). Descriptive statistics and correlations among variables are presented in Table II. As the correlation matrix demonstrates, no serious multicollinearity among independent variables was detected. Analysis To test the hypotheses of the present study, a multinomial logit (MNL) analysis was utilized. MNL performs maximum-likelihood estimation of models with discrete dependent variables. It is intended to be used when the dependent variable takes on more than two mutually exclusive outcomes that have no natural ordering (Greene, 1993). In the present study, the general form of this MNL equation was: lneP(J/K) = a + biX + e (i = 1, 2, 3, ... n), where P(J/K) is the relative probability of choosing one type of gainsharing (J) over another type 5 2 (K). For example, P(Simple/Impro) is the probability of choosing the Simple Scanlon plan over the Improshare plan, and P(Rucker/Custom) is the probability of choosing the Rucker plan over customized plans. X is a vector of exogenous variables. Table III shows the MNL results for the total sample. Results and Discussion The results generally supported the congruence hypothesis; though there were some exceptions. Results for Congruence Hypotheses The results strongly supported the hypothesis that labor-intensive organizations are more likely to choose labor-cost focused plans (Hypothesis 1). The variable, labor intensity, had significant and positive relationships with P(Simple/Custom) and P(Impro/Custom). The relationship between labor intensity and P(Multicost/Impro) was found to be significant and negative, as expected. Also, the variable, labor intensity, had positive and significant relationships with P(Multicost/Custom) and P(Rucker/Custom), which implies that customized plans are least likely to be chosen by labor-intensive organizations. The reason for this could be that customized plans usually do not focus on labor costs or labor productivity at all, whereas the Multicost and Rucker plans include labor costs within their performance measures. The hypothesis that small organizations are more likely to choose administratively simpler plans (i.e., the Simple Scanlon or Rucker plans) than complex ones (the Multicost Scanlon, Improshare, or customized plans) (Hypothesis 2) received strong support. As expected, the variable, small organization, had significant and positive relationships with P(Simple/Impro), P(Rucker/Impro), P(Rucker/Custom), and P(Simple/Multicost), and a significant and negative 6 2 relationship with P(Multicost/Rucker). One unexpected finding was the negative and significant relationship between the variable, small organization, and P(Simple/Rucker), which implies that small organizations are more likely to choose the Rucker plan than the Simple Scanlon plan. Since the Rucker plan is more complex and requires more complicated data than does the Simple Scanlon plan, it is unclear why the Rucker plan is preferred to the Simple Scanlon plan among small organizations. The results supported the hypothesis that nonmanufacturing organizations are less likely to choose the Improshare plan than other plans (Hypothesis 3). The variable, nonmanufacturing, had a positive relationship with P(Simple/Impro) and a negative relationship with P(Impro/Custom). The results indicated that nonmanufacturing organizations are less likely to choose Improshare plans than the Simple Scanlon or customized plans. The results did not support the hypothesis that organizations trying to improve labor productivity are more likely to choose the Simple Scanlon or Improshare plans than the Multicost Scanlon, customized, or Rucker plans (Hypothesis 4). Although the variable, goallabor productivity, showed an expected positive sign in the P(Impro/Custom) equation and an expected negative sign in the P(Multicost/Impro) equation, these coefficients were not significant. The results did indicate that organizations trying to reduce nonlabor costs are more likely to prefer the Multicost Scanlon plan to the Improshare plan, as hypothesized (Hypothesis 5). The variable, goal-nonlabor costs, had significant and negative relationships with P(Simple/Custom), P(Impro/Custom), and P(Simple/Multicost), and a significant and positive relationship with P(Multicost/Impro). These results clearly indicated that the Multicost Scanlon and customized plans are preferred to the Simple Scanlon and Improshare plans if organizations 7 2 consider the reduction of nonlabor costs as an important goal. Interestingly, it was found that the Multicost Scanlon plan is more likely to be chosen than the Rucker plan by these organizations. Goal-nonlabor costs showed a positive and significant sign in the P(Multicost/Rucker) equation. The reason for this result might be that the emphasis of the Rucker plan on nonlabor savings is weaker than that of the Multicost Scanlon plan. At the same time, the results did not support the hypothesis that organizations aiming for quality improvement are more likely to choose customized plans than standard plans (Hypothesis 6). Although the variable, goal-quality, had the expected negative relationship with P(Simple/Custom), P(Multicost/Custom), P(Rucker/Custom), and P(Impro/Custom), the coefficients were all insignificant. There was weak support for the hypothesis that if the improvement of labor relations were an important goal when implementing gainsharing, Scanlon-type plans would be preferred to other plans (Hypothesis 7). The significant and negative relationship between the variable, goal-labor relations, and P(Multicost/Rucker) implies that organizations aiming to improve labor relations by gainsharing prefer the Multicost Scanlon plan to the Rucker plan. In addition, the coefficients for P(Multicost/Custom), P(Simple/Impro), P(Multicost/Impro), and P(Simple/Rucker) also showed expected, although insignificant, signs. Results for Control Variables The results did not substantiate the hypothesis that unionized organizations are more likely to choose Scanlon-type plans over non-Scanlon plans (Hypothesis 8). The coefficients were simply not significant. Either unions do not have the strong preferences which I anticipated or perhaps they are not generally influential regarding the type of gainsharing plan adopted. 8 2 There was some support for the hypothesis that organizations with outside consultant involvement are more likely to choose standard plans than customized plans (Hypothesis 9). The variable, consultant, had significant and positive relationships with P(Simple/Custom) and P(Impro/Custom), suggesting that Simple Scanlon and Improshare plans are preferred to customized ones when consultants are involved in program design. Simple Scanlon and Improshare plans seem to be particularly pushed by outside consultants. The results showed some differences in the choice of gainsharing types between earlier programs and those introduced since 1986. The variable, since 1986, showed a significant and positive relationship with P(Rucker/Improshare) and a significant and negative relationship with P(Simple/Rucker). Although further scrutiny is warranted, these results may reflect the fact that the Improshare program is the newest plan, developed in 1973 by Mitchell Fein. Thus, there was a weak indication that there are different patterns of program choice between earlier and later adopters of gainsharing. The results showed some significant regional variances in program choice. Organizations in Canada are more likely to prefer Simple Scanlon, Multicost Scanlon, and Improshare plans to customized plans than those in the Northcentral part of the U.S. The variable, Canada, was significantly associated with P(Simple/Custom), P(Multicost/Custom), and P(Impro/Custom). This trend can be explained by the fact that gainsharing programs in Canada were recently introduced by consultants, and thus standard programs are more popular in Canada. Organizations in the South are more likely to choose Simple Scanlon over Rucker plans than are those in the Northcentral states. Also, organizations in the West are more likely to prefer Multicost Scanlon to Rucker plans. The variables, South and West, had significant and positive 9 2 relationships with P(Simple/Rucker) and P(Multicost/Rucker), respectively. These regional/national patterns deserve further scrutiny in future research. In sum, there are different patterns of program choice among organizations located in different regions. Conclusion and Implications Utilizing multinomial logit analyses of survey data from 217 organizations with experience of gainsharing plans in North America, I examined congruence explanations of the choice of a particular type of gainsharing plan. The results provide an understanding of the general pattern of usage of the various gainsharing plans. Clearly, the results show that congruence factors are important determinants of program choice. The theoretical implications of the present study are as follows. First and foremost, the choice of a particular type of gainsharing plan was generally found to be influenced by congruence factors. Among congruence factors, situational factors (i.e., labor intensity, organizational size, and nonmanufacturing) were clearly found to be related to the particular type of gainsharing plan selected by organizations. I found evidence that program goals (such as reducing nonlabor costs and improving labor relations) have some relationship to the probability of program adoption; although in general the relationships were weaker than they were for situational factors. Explicit goals do seem to carry some weight, suggesting that future researchers should not ignore managerial attitudes and organizational goals. There have been some attempts to show that congruence (or fit) of management systems is correlated with organizational performance (Arthur, 1994; Huselid, 1995; Lawler, 1988; Osterman, 1994), whereas little research has been carried out to examine whether congruence serves as a criterion in the choice of an innovation. The present study shows that organizations 0 3 do consider congruence factors when they design gainsharing programs. Second, the present study also found that other factors influence the choice of a gainsharing plan. Specifically, organizations that had consultant help were more likely to choose standard plans than customized plans. There were some systematic differences in the choice of gainsharing types between earlier and later adopters, and different patterns of program choice among organizations located in different regions. The results of this study carry a number of practical implications for organizations considering adopting a gainsharing program, and for union representatives, who are sometimes involved in those decisions. First, the decision to involve a particular consultant in the decision process may be implicitly a decision to adopt a particular type of gainsharing (especially the Simple Scanlon or Improshare plans) that may or may not be the most appropriate one for the given organization and its goals. Moreover, organizations need to consider more explicitly the feasibility of particular programs given their ability to produce needed information and their administrative expertise – there is evidence that smaller organizations may be wise to adopt simpler types of gainsharing, and that some work processes, particularly in nonmanufacturing, are not amenable to the type of time-study needed for the Improshare plan. There is some evidence from the patterns of adoption that different gainsharing programs are more suitable in labor-intensive settings than in others; although the explicit goals of the program (e.g., the minimization of nonlabor costs) should also be weighed in program selection. Getting these issues onto the table in the adoption process can minimize later conflict over the program and the probability of plan failure in the first year of installation. There has been little research to date on the reasons why individual organizations adopt 1 3 one gainsharing program over another. I hope that this study will open up this area of research and will encourage other examinations – possibly of a broader nature than was possible with this data set – such as into why some organizations adopt gainsharing, others adopt profit-sharing, and others adopt total quality management initiatives, teams, or other employee involvement initiatives. 2 3 References Abrahamson, E. (1991). Managerial fads and fashions: The diffusion and rejection of innovations. Academy of Management Review, 16(3), 586-612. Alchian, A.A., & Demsetz, H. (1972). Production, information costs, and economic organization. American Economic Review, 62(5), 777-795. Arthur, J.B. (1994). Effects of human resource systems on manufacturing performance and turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3), 670-687. Barringer, M.W., & Milkovich, G.T. (1998). A theoretical exploration of the adoption and design of flexible benefit plans: A case of human resource innovation. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 305-324. Bazerman, M., & Graham-Moore, B. (1983). PG Formulas: Developing a reward structure to achieve organizational goals. In B. Graham-Moore & T.L. Ross (Eds.), Productivity gainsharing (pp. 40-61). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Bullock, R.J., & Tubbs, M.E. (1990). A case meta-analysis of gainsharing plans as organization development interventions. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 26(3), 383-404. Cooper, C.L., Dyck, B., & Frohlich, N. (1992). Improving the effectiveness of gainsharing: The role of fairness and participation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37, 471-490. Cotton, J.L. (1993). Employee involvement: Methods for improving performance and work attitudes. London: Sage Publications. DiMaggio, P.J., & Powell, W.W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(April), 147-160. 3 3 Eisenhardt, K.M. (1988). Agency- and institutional-theory explanations: The case of retail sales compensation. Academy of Management Journal, 31(2), 488-501. Globerson, S., & Parsons, R. (1988). IMPROSHARE: An analysis of user responses. In A. Mital (Ed.), Recent developments in production research (pp. 3-7). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers. Goodstein, J.D. (1994). Institutional pressures and strategic responsiveness: Employer involvement in work-family issues. Academy of Management Journal, 37(2), 350-382. Gowen, C.R. (1991). Gainsharing programs: An overview of history and research. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 11(2), 77-99. Gowen, C.R., & Jennings, S.A. (1991). The effects of changes in participation and group size on gainsharing success: A case study. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 11(2), 147-169. Graham-Moore, B. (1990). Formulas for developing a reward structure to further organizational goals. In B. Graham-Moore & T.L. Ross (Eds.), Gainsharing: Plans for improving performance (pp. 48-80). Washington, D.C.: The Bureau of National Affairs. Greene, W.H. (1993). Econometric analysis. Second edition. New York: Macmillan. Hatcher, L., & Ross, T.L. (1991). From individual incentives to an organization-wide gainsharing plan: Effects on teamwork and product quality. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12, 169-183. Hewitt Associates. (1989). Compensation trends and practices. Lincolnshire, IL: Hewitt Associates. Huselid, M.A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, 4 3 productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal 38(3), 635-672. Ingram, P., & Simons, T. (1995). Institutional and resource dependence determinants of responsiveness to work-family issues. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 14661482. Jarrett, J. E. (1990). Gainsharing and the government sector. In B. Graham-Moore & T.L. Ross (Eds.), Gainsharing: Plans for improving performance (pp. 174-199). Washington, D.C.: The Bureau of National Affairs. Jensen, M.C., & Meckling, W.H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305-360. Jones, D.C., Kato, T., & Pliskin, J. (1997). Profit sharing and gainsharing: A review of theory, incidence, and effects. In D. Lewin, D.J.B. Mitchell, & M.A. Zaidi (Eds.), The Human Resource Management Handbook, Part 1 (pp. 153-173). London: JAI Press. Kaufman, R.T. (1992). The effects of IMPROSHARE on productivity. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 45(2), 311-322. Kim, D.-O. (1996). Factors influencing organizational performance in gainsharing programs. Industrial Relations, 35(2), 227-244. Kim, D.-O. (1999). Determinants of the survival of gainsharing programs. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 53(1), 21-42. Kim, D.O., & Voos, P.B. (1997). Unionization, union involvement, and the performance of gainsharing programs. Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations, 52(2), 304-332. Lawler, E.E. (1986). High-involvement management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. 5 3 Lawler, E.E. (1988). Choosing an involvement strategy. Academy of Management Executive, 2(3), 197-204. Markham, S., Scott, D., & Little, B.L. (1992). National gainsharing study: The importance of industry differences. Compensation and Benefits Review, August, 36-40. Moore, B.E., & Ross, T.L. (1978). The Scanlon way to improved productivity: A practical guide. New York: John Wiley and Sons. O’Dell, C.O., & McAdams, J. (1987). People, performance, and pay. Houston, TX: American Productivity Center. Osterman, P. (1994). How common is workplace transformation and who adopts it? Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 47(2), 173-188. Pfeffer, J., & Davis-Blake, A. (1987). Understanding organizational wage structures: A resource dependence approach. Academy of Management Journal, 30(2), 437-455. Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G.R. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. New York: Harper & Row. Ross, T.L. (1990). Gainsharing application in the service sector. In B. Graham-Moore & T.L. Ross (Eds.), Gainsharing: Plans for improving performance (pp. 253-265). Washington, D.C.: The Bureau of National Affairs. Ross, T.L., & Ross, R.A. (1990). Solving some measurement issues. In B. Graham-Moore & T.L. Ross (Eds.), Gainsharing: Plans for improving performance (pp. 81-99). Washington, D.C.: The Bureau of National Affairs. Schuster, M. (1984). Union-management cooperation. Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn. U.S. General Accounting Office. (1981). Productivity sharing programs: Can they contribute to 6 3 productivity improvement? GAO/AFMD No. 81-22. Gaithersburg, MD: U.S. General Accounting Office. Williamson, O.E. (1975). Markets and hierarchies: Analysis and antitrust implications. New York: Free Press. Williamson, O.E. (1981). The economics of organization: The transaction cost approach. American Journal of Sociology, 87, 548-557. 7 3 TABLE I Characteristics of Major Gainsharing Programs Plan type Simple Scanlon plan Multicost Scanlon plan Rucker plan Improshare plan Formula base for bonus Payroll / Sales value of production Payroll, material, overhead / Sales value of production Payroll / Value added Actual hours / Standard labor hours Typical employee share 75% of gain 75% of gain 50% of gain 50% of gain Information needed Payroll, production Payroll, production, revenues, material cost, overhead, and other costs Payroll, production, material cost Time standards and production levels Expertise needed Basic accounting Advanced accounting Intermediate accounting Industrial engineering and extensive accounting Employee vote in implementation decision Yes Yes Yes (optional) Usually no Suggestion system Formal Formal Formal Not part of plan but may be added Employee Involvement Screening and production committee Screening and production committee Screening and production committee (optional but often used) Productivity team (optional) 9 3 TABLE II Descriptive Statistics and Correlations 1. Simple Scanlon Plan 2. Multicost Scanlon Plan 3. Rucker Plan 4. Improshare Plan 5. Customized Plans 6. Labor Intensity 7. Small Organization 8. Nonmanufacturing 9. Goal-Labor Productivity 10. Goal- Nonlabor Cost 11. GoalQuality 12. GoalLabor Relations 13. Union 14. Consultant 15. Since 86 16. Northcentral 17. Northeast 18. South 19. West 20. Canada Mean S.D. .15 .36 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 .15 .36 -.18 .14 .34 -.16 -.16 .34 .22 .47 .42 -.30 -.23 -.30 -.23 -.28 -.21 -.38 .66 .31 .47 .46 .06 .14 -.01 -.13 .04 .33 .20 -.15 -.30 -.10 .04 .09 .28 .20 -.05 -.03 -.18 .11 -.00 .14 .78 .41 .01 -.05 .09 .09 -.15 .04 .17 -.02 .51 .50 -.05 .20 -.07 -.19 .14 .01 -.07 -.03 .08 .65 .48 -.06 .06 .01 -.10 .10 -.01 .01 -.08 .06 .33 .40 .49 -.01 .09 -.06 -.05 .05 .07 -.01 -.10 .11 .14 .22 .53 .81 .68 .64 .14 .12 .04 .05 .50 .40 .47 .48 .35 .33 .20 .22 -.07 .10 -.06 -.04 .04 -.01 -.04 .06 .02 .02 .02 -.03 .05 -.06 .13 -.04 -.10 .08 .12 .09 .05 -.11 -.08 -.03 .08 .08 -.12 -.05 -.04 .07 -.02 .11 .03 -.25 .07 .04 -.06 .07 .02 -.11 .07 .02 -.08 -.04 .02 .01 .15 -.10 -.24 .15 .02 -.02 .12 -.12 -.01 .07 -.17 .03 .06 -.01 -.04 .01 .16 -.07 -.04 .22 -.12 -.02 .00 .03 .01 -.01 .05 -.03 .03 .06 -.11 -.00 .04 -.00 .04 -.08 .09 .01 .01 -.04 .06 -.05 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 .05 .01 .02 .04 -.02 -.04 .10 -.07 -.04 -.04 .07 -.07 -.07 -.03 .11 -.12 -.05 .11 -.11 -.01 .11 .05 -.04 -.06 .09 -.03 -.54 -.50 -.27 -.30 -.15 -.08 -.09 -.07 -.08 -.04 0 4 TABLE III Multinomial Logit Estimates of the Odds of Choosing Types of Gainsharing Plans Variables P(Simple/ P(Multicost/ P(Rucker/ P(Impro/ P(Simple/ P(Multicost/ P(Rucker/ P(Simple/ P(Multicost/ Custom) Custom) Custom) Custom) Impro) Impro) Impro) Rucker) Rucker) Labor Intensity 1.47*** .97* 1.91*** 2.09 -.62 -1.13** -1.8 -4.4 -9.4 (.54) (.52) (.61) (.47) (.52) (.53) (.59) (.64) (.65) Small Organization .45 -.64 1.78*** -.56 1.01* -0.8 2.33*** -1.33 -2.42*** (.58) (.65) (.62) (.55) (.53) (.63) (.57) (.63) (.70) Nonmanufacturing .45 -1.06 -1.10 -2.18 2.62** 1.11 1.08 1.54 .03 (.81) (1.18) (1.09) (1.25) (1.20) (1.52) (1.42) (1.05) (1.41) -0.2 -0.5 1.09 .90 -.92 -.95 .19 -1.11 -1.14 Goal-Labor Productivity (.61) (.58) (.74) (.55) (.59) (.58) (.72) (.76) (.77) Goal-Nonlabor -1.05* .17 -.92 -1.35** .31 1.52*** .44 -1.3 1.08* (.56) (.57) (.59) (.48) (.50) (.53) (.53) (.61) (.64) Goal-Quality -4.5 -4.1 -2.1 -4.2 -0.3 0.1 .21 -.24 -.20 (.57) (.59) (.63) (.50) (.50) (.54) (.54) (.62) (.66) Goal-Labor Relations -.15 .01 -1.15* -.57 .43 .58 -.57 1.00 1.15* (.52) (.51) (.59) (.45) (.48) (.49) (.55) (.61) (.63) Union -.14 -.23 -0.1 -.22 .08 -0.1 .21 -.13 -.22 (.53) (.52) (.59) (.46) (.49) (.50) (.54) (.61) (.63) Consultant 1.30* .56 .96 1.06* .24 -4.9 -0.9 .34 -4.0 (.75) (.61) (.76) (.55) (.75) (.64) (.76) (.91) (.83) Since 1986 -.45 .03 -.96 -.21 -2.4 .24 1.17** -1.41** -.93 (.55) (.55) (.67) (.48) (.48) (.52) (.60) (.66) (.70) Northeast .27 .22 -.32 -.16 .43 .38 -.17 .60 .55 (.71) (.71) (.74) (.65) (.63) (.67) (.65) (.72) (.77) South -.30 -1.24 -34.68 -.24 .06 -1.00 -34.44 22.38*** 21.44 (.71) (.85) (.00) (.59) (.68) (.86) (.00) (.96) (----) West -.04 .66 -34.57 -1.0 -.06 .76 -34.48 21.54 22.22*** (1.60) (1.33) (.00) (1.33) (1.41) (1.13) (.00) (----) (1.45) Canada 22.87*** 21.77** 21.74 23.23*** -.35 -1.46 -1.50 1.14 .04 (1.35) (1.60) (----) (1.21) (.92) (1.21) (1.2) (1.35) (1.60) Constant -1.24 -.79 -3.30** -.68 -.56 -.12 -2.62** 2.06 2.50* (1.07) (.98) (1.35) (.89) (1.05) (1.01) (1.31) (1.44) (1.42) Log Likelihood = -268.44; Chi-square = 130.19 ***; N=217; * p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01, all two-tailed; standard errors in parentheses. P(Simple/ Multicost .50 (.59) 1.09* (.67) 1.51 (1.21) .03 (.65) -1.21** (.62) -.04 (.62) -.16 (.56) 0.9 (.58) .74 (.82) -.48 (.59) .05 (.74) .94 (.96) -.69 (1.45) 1.10 (1.37) -.45 (1.18) 1 4 Notes 1. Indeed, there is even a belief that gainsharing will work only in organizations where some type of tangible product is manufactured (Lawler, 1986). However, studies that have examined this issue have only obtained insignificant results. Bullock and Tubbs (1990), in their correlation analysis based on 33 reported case studies, found insignificant associations between the manufacturing industry and the success of gainsharing. Markham, Scott, and Little (1992), in their cross-tabulation analysis of 219 active gainsharing programs, did not find that gainsharing programs in the manufacturing industry were systematically different in terms of bonus payout records, participant satisfaction, and program longevity from those in other industries. 2. Alternatively, they may pick up the effect of regional/national industry patterns which are not adequately captured by the manufacturing/nonmanufacturing variable. 3. Since the two surveys used a different definition of gainsharing than that adopted in the current study, they are not directly comparable. For instance, in both surveys, customized plans include customized profit sharing plans as well as customized gainsharing plans. Also, O’Dell and McAdams (1987) did not include any Rucker plans in their sample. Consequently, the only meaningful comparison among these two surveys and ours is the examination of the relative proportion between Scanlon-type plans and Improshare plans. 4. As found in the present study, it is generally believed that gainsharing is more prevalent in the Midwest and Northeast than in any other regions. For example, the survey by Hewitt Associates also revealed that gainsharing programs were found to be more prevalent in the Midwest and the Northeast (Hewitt Associates, 1989; Jones, Kato, & Pliskin, 1997).