celebration of the hero in japan and china

advertisement

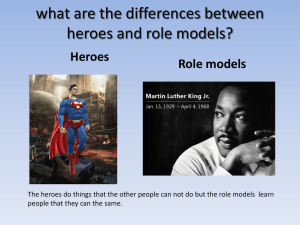

CELEBRATION OF THE HERO IN JAPAN AND CHINA In China and Japan, a panoply of heroes, both secular and religious, were venerated to many different ends. Some were used to legitimize political power, some to subtly criticize or subvert it. Others were simply celebrated the life of the common man (or woman) living their everyday life. In this lesson is a comparative survey, to which can be added a look at how other societies (including our own) choose, use, and value role models. Grade Level This lesson was developed for grades 7-12. Purpose In this lesson students identify and examine different types of heroes, then compare how heroes are idolized in China, Japan, and the United States. Concepts • Types of hero • Role model/Archetype • Propaganda • Subversive role of art Key Ideas—See Teacher Notes Materials Political figures Inauguration Portraits of Emperor Qianlong, the Empress and Eleven Imperial Consorts, 1736, CMA 1969.31 Religious figures Album of Daoist and Buddhist Themes: Procession of Daoist Deities: Leaf 8, 1200s, CMA 2004.1.8 White-Robed Guanyin, late 1200s, CMA 1972.160 Scholarly figures Purification at the Orchard Pavilion, CMA 1671, 1977.47 Thirty-Six Immortal Poets, mid-1700s, CMA 1960.183 Theatrical figures Ichikawa Danjuro VII as Kan Shojo (from the series Famous Kabuki Plays), 1814, CMA 1985.333 Act VII of the Storehouse of Loyalty, late 1790s, CMA 1985.360 Everyday figures— The Mie River near Yokkaichi (Station 44) from the series Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido, 1833, CMA 1948.307 Sudden Rain at Atake and Ohashi (from the series 100 Views of Famous Places in Edo) 1857, CMA 1921.318 Herdboys and Oxen in Landscape, 1200s, 1999.216.1-.2 The Knickknack Peddler, 1212, 1963.582 Schirokauer, Conrad. A Brief History of Chinese and Japanese Civilizations. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers, 1989. Procedure 1. Discuss the universal nature of hero worship Ask students to identify people they consider heroes. Make a class list and group the individuals by type: political, religious, military, entertainment celebrities, pop stars; make sure to include ordinary men and women who have in some way made an outstanding contribution. Write the class list on the board or on an overhead and have students copy it in their notebooks. 2. Ask students to describe how they show their admiration for their heroes. Again make a class list and have students add it to their notebooks. 3. Initiate a class discuss about the definition of a role model and ask students to describe how they have been influenced by someone they consider a role model. Have them describe any experience, theirs or someone else's. Ask students how many consider the heroes they have named to be a role model--either for themselves or for others? 4. Explain the thesis of this lesson: by looking at examples students will explore, then discuss, how China and Japan celebrated heroes throughout their history, up to the modern period. 5. Have students look at the Inaugural Portraits of the Emperor Qianlong, his Empress and Eleven Imperial Consorts. Tell students that this is one of the most powerful imperial portraits in all of Chinese art. Explain to students the portrait was painted by a European, a Jesuit priest who lived and worked at the Chinese court for many years. Ask students why they think the emperor commissioned such a portrait (as a symbol of political power) and why did he choose a non-Chinese painter for such an important image? (It was a sign of favor to the artist, but also to show that he was not only a connoisseur of the arts but also willing to accept new ideas.). Ask them if they can think of any other ways this kind of official portraiture has been used in China (in modern times an enormous portrait of Mao Zedong has hung for many decades on the Gate of Heavenly Peace at the entrance to Beijing's Forbidden City). 6. Have students look at the images of religious figures from the CMA (see Teacher Notes for information about these images). Ask students if they notice differences in the way the Chinese and Japanese portray important religious figures. 7. Next have students look at the look at the portrayals of the Chinese scholars and explain to students why scholars were held in such esteem in China. Ask students how the depiction of the scholars differs from that of the religious figures. After a class discussion, have students write a short paragraph in their notebook summarizing the ideas. 8. Explain to students the "floating world" (see Teacher notes) then ask then to look at the images from Kabuki and the prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige. How do these images differ from the works they have just looked at? Has the portrayal of the hero changed? (The medium is different—wood-block prints—and the subjects are everyday people working at their professions, not officials or priests). 9. Have students look at the images of the Herd Boys and the Knickknack Peddler and write a short paragraph comparing they way the Chinese artists showed everyday people at work compared with Japanese images they looked at. 10. Review the images presented in this lesson and ask students to categorize the images: warrior, religious hero, theatrical celebrity, and everyday people. Evaluation A. For homework, students are to write a comparison between one of the heroic types from the lesson and one of our modern heroes. B. Ask students to create a “Celebrate the Hero” T-chart with East Asia on one side and the West on the other. Have students work with a partner to complete the chart using the information from this lesson and their own expertise in Western popular culture. Enrichment A. A comparison with how American popular culture celebrates the hero is easily done (ask for donations of popular magazines). Have students work in small groups to create a collage of “Today’s American Hero” from the magazine images. Then discuss the collages and have students write about the similarities and differences between the collages and the above study of East Asian heroes. B. To further examine how heroes are celebrated, examine with your students art from the Cleveland Museum’s European collection, particularly from 1400-1800. Warrior heroes, religious heroes, and the common man are universal archetypes, and students can identify clear comparisons between Asia and Europe. C. A comparison with the celebration of Mao (“the cult of Mao”) is an appropriate modern history tie-in. See the History Alive (Teacher’s Resource Institute http://www.historyalive.com ) lesson on Mao, complete with images comparing the cult of Mao with the celebration of Chinese emperors. Social Studies Benchmarks 9.3 People in Societies, Diffusion. Explain how advances in communication and transportation have impacted religion, popular culture, political systems and religions. 9.3 Citizen Rights and Responsibilities. Analyze how governments and other groups have used propaganda to influence public opinion and behavior. 9.1 Social Studies Skills and Methods. Detect bias and propaganda in primary and secondary sources of information. 9.2 Social Studies Skills and Methods. Evaluate the credibility of sources for logical fallacies, consistency of arguments, unstated assumptions and bias. This lesson plan was developed by Sarah Davis, High School Social Studies Teacher, Shaker Heights City Schools, Shaker Heights, Ohio Key Ideas—Teacher Notes • • • Political figures The tradition of imperial portraits dates from the earliest dynasties in China. One of the earliest known dates from the late 7th century and represents 13 emperors with their attendants. Japan had an equally long tradition of imperial portraiture, but the Japanese emperors often chose to be portrayed in the clothing of religious figures or from a previous age, often the Heian period, considered one of Japan's golden ages. Religious figures Images of religious heroes decorated many temples and individual homes. Daoism celebrated Eight Immortals who are portrayed in murals, wall carvings, and prints to represent long life and immortality up to the present day. These Eight Immortals (seven men and one woman) were human beings who are believed to have gained immortality through performing good deeds and making sacrifices. Daoism was an indigenous Chinese belief system based on the Dao, or Way, a powerful force capable of creating the universe from an empty void. From the Dao is generated the constantly moving energy, or qi, that is found in all things. To realize the Dao one must live simply, in harmony with nature, and learn not to struggle against forces one can't control. Daoism later became an organized religion based on these philosophical principles. Buddhism has since its inception into China made use of pictorial images as teaching tools. In Japan's Zen Buddhist temples it was common practice to have statues of renowned teachers as a way of keeping their influence alive. Scholarly figures In China, the scholar-official, a bureaucrat who served the emperor, formed the political and social elite in the class hierarchy. To enter the imperial bureaucracy, the equivalent of America's civil service, a candidate had to pass a series of extremely arduous examination based on the memorization of the Confucian classics, the ability to wrote prose and poetry • reflecting Chinese literary traditions, and to record their writings in beautiful calligraphy. To have a son pass the examinations was the goal of every family who could afford it, as it brought prestige and economic gain for the entire family. Although in reality most scholars came from a relatively wealthy background in order to pay for all of the tutors, books, and exam preparation, a few rose from humble families, making the Chinese civil service in some ways a meritocracy. Many scholar-officials retired from government service to spend their time painting and writing poetry, becoming an important part of the Chinese artistic tradition. Theatrical figures Kabuki was a new type of theatre performance that developed in the late 16th century. It evolved from the popular Japanese puppet theatre, replacing with puppets with live actors. In Kabuki adult male actors play all the roles and the productions feature elaborate sets and magnificent costumes. Kabuki plots deal with themes such as conflicts between moral duty and personal desire, historical events, and even ghost stories. Kabuki plays often expressed the political ideas of the rising merchant class who patronized the theatres. Leading actors usually specialized in certain types of roles, and audiences come as much as to applaud a favorite actor as to enjoy the drama. Kabuki actors are the equivalent of Hollywood celebrities and pop stars rolled into one. Wood-block Prints and the "Floating World" Wood-block printing became a popular in Japan in the 15th century, and the first images were made in temples and given away to believers. They generally portrayed deities or sacred writings. By the Edo period (1600-1868) woodblocks became the favorite medium for portraying the beautiful courtesans and handsome Kabuki actors of the "floating world." Even in this secular context the connection with Zen Buddhism cannot be escaped as the concept of the "floating world" came from the Buddhist notion that worldly beauty and joys are fleeting. In the hedonistic world of Edo Japan, this concept was turned on its head and the idea became to enjoy oneself to the fullest as time, beauty, and joy was transitory. Single-sheet wood-block prints of the most prominent actors and most famous beauties were produced by a succession of talented artists, engravers, and printers. A new interest in the everyday world and a new market among the relatively well-to-do merchant class led to the proliferation of these prints. It is estimated that millions of these portraits prints were produced between 1658 and 1858, when the leading artists, Hokusai and Hiroshige, turned. to landscape prints that portrayed common people going about their everyday activities.