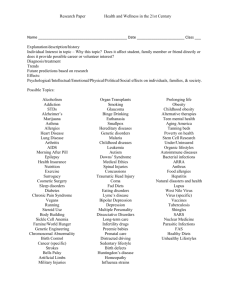

Screening for and Assessment of Co-occurring Substance

advertisement