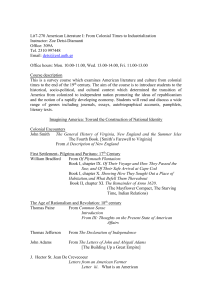

Hierarchies of Race and Gender in the French Colonial Empire

advertisement