Howard, Tenisha - eCommons@Cornell

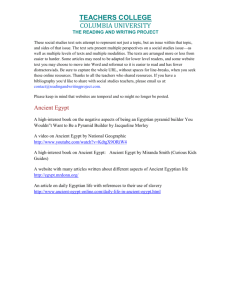

advertisement