ABC vs. German Cost Accounting: A Comparative Analysis

advertisement

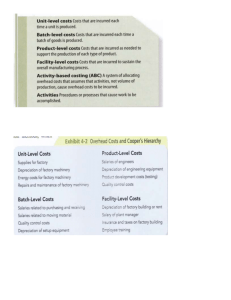

GERMAN COST ACCOUNTING VS. ACTIVITY-BASED COSTING Shirley A Polejewski, PhD Professor of Accounting University of St. Thomas 2115 Summit Avenue Saint Paul, Minnesota 55105 INTRODUCTION It appears that Activity-Based Costing is widely used in cost/managerial accounting as a cost measurement, yet accounting practices can differ widely between countries. To be able to recognize difference and similarities in seemingly identical practices between countries provides an opportunity for improvement and allows managers to draw managerial implications in light of the increasing internationalization of companies. This paper compares the USA Activity-based Costing (ABC) and the German (GPK) Activity-based costing. The paper establishes differences based on purpose, cost, concepts construction and cost allocation, and quantity and quality of cost information. From this research it appears that many of the enterprises in the USA as well as those in other countries should take a look at the ways their international counterparts successfully measure and manage organization performance, in order to resolve limitations in North American practices and in referencing the German Cost Accounting system. HISTORY OF PRODUCT COSTING There are significant compromises in a key part of the system, the costing out of products, which misrepresent the true behavior of the business. Overhead, specifically, has been allocated in such a simplistic manger usually on labor hours consumed. Initiatives taken in plants to regain competitiveness have not been captures and supported in the accounting records. Managers could be mislead, develop inappropriate strategies, and make bad decisions. For example, a small specialty order requiring more design, scheduling and attention, i.e., increased overhead because of the runtime and low direct labor. The small order would inaccurately appear to be better than larger orders; the plant would be pushed in the wrong direction. With the development of activity-based costing (ABC) this would then provide an opportunity for management to bring these overhead allocations into line with the way the plant actually operates. The activities, which cause the costs, are identified so that the products, which cause the activity, can pay for them. ABC is not a radical change but a fine-tuning of applying overhead to products. ABC has the potential to significantly improve the usefulness of accounting as a decision support system for manager’s strategic moves in rebuilding competitiveness. The full cost of a product includes direct labor, material, variable overhead and fixed costs. Direct labor and materials are observed and measured by industrial engineers and maintained as “standards.” The overhead costs are captured and reported by responsibility centers, departments or plants. The difficulty is what to do about tying overhead costs to products. Those who advocate variable costing state that overhead costs are sunk or fixed and will not change with most management decisions; therefore overhead costs should be expensed monthly as a general cost of doing business. Advocates of full costing believe that the cost of the product must show the full costs of the product, which means more costs are capitalized and put into inventory with the product rather than expensed when costs occur. Full absorption costing is most common for external reporting but from a management decision-making, this costing has important implications. ACTIVITY-BASED COSTING Activity based costing has been the new approach to solve some of the problems and provide management with better information. Activity-based costing (ABC) developed by Harvard’s Robert Kaplan and Robbin Cooper allocates staff and overhead costs to products on the basis of how the product actually consumes or causes these activities. The process is similar to the one used by engineers and estimators in developing a bid or estimate of the cost of a project. They search for systematic, cause and effect linkages between the product and costs, before resorting to gross across-the board allocations. ABC calls these linkages “cost driver.” Companies use things such as labor hours machine hours, floor space used, number of set-ups, order, movements, size and weight, complexity, and sales costs as “drivers.” Costs are first accumulated and then allocated to the product by the appropriate driver, i.e., cause. For example, a product using 30% of the space might get 30% of the space costs; this then gives a more accurate result and often a very different picture of costs and profitability of products and product lines. Pat Romano, editor of Management Accounting and director of NAA Research summarized developments in ABC by saying, “Activity Accounting is a technique for understanding costs.” 1 It is very difficult to estimate the potential costs from running a business with inaccurate information and ABC is an opportunity to improve the accuracy of accounting reports in modeling the company. One should note that, where a company produces a narrow range of similar products, ABC may offer limited benefits but for firms that produce a diverse range of high-volume and low-volume products, and ABC system is likely to be justified. 2 ABC is not a fad or a panacea for all that ails many industries; it is a progression of information system of industry. Kaplan and Cooper reiterate, “ABC is not designed to trigger automatic decisions but designed to provide more accurate information about production and support activities so that management can focus its attention on the products and processes with the most leverage for increasing profits. ABC appears to be less revolutionary than evolutionary as it is a matter of formally examining processes and products to find out how they cause expenses and then seeing how they bear the costs. Companies that implement ABC do run the risk of spending too much time, effort and money on gathering data that is collected. Too many details can prove frustrating for managers involved in ABC, on the other hand, a lack of detail leads to insufficient data. One should note that, where a company produces a narrow range of similar products, ABC may offer limited benefits but for firms that produce a diverse range of high-volume and low-volume 1 2 Romano, Patrick L., “Trends in Management Accounting,” Management Accounting, August 1990, p53-56. Drury, Colin, “Product Costing in the 1990s,” Accounting (UK), May 1990, p 126 products, and ABC system is likely to be justified.3 Another reason of limited benefits is that maybe that the external accounting rules puts the interests of creditors before those interests of shareowners. GERMAN COST ACCOUNTING: (Grezplankostenrechnung or “GPK”) Flexible margin costing, or GPK is a time-tested cost accounting used by many companies in German-speaking countries. GPK is about marginal costing instead of full costing, short-term decision support instead of long-term and cost center instead of activities and processes. Management accounting has been more important to companies in German-speaking countries, such as Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, than to companies in the USA. Perhaps one of the reasons why management accounting is important maybe that the external accounting rules puts the interests of creditors before those interests of shareowners.4 Hans Georg Plaut, a practitioner, and Wolgang Kilger, a cost accounting researcher, developed GPK in the 1950s and 1960s. Both men were focused on developing cost accounting methods to support decision-making. Similar to direct costing, the most important idea behind GPK is that fixed costs aren’t charged to products. If they were, managers would be induced to make incorrect short-term decisions, such as for pricing and make-or-buy decisions. In practice, however, GPK can be combined with a multilevel allocation of fixed cost-type costs. GPK consists of four important elements: cost-type accounting, cost center accounting, product cost accounting, and contribution margin accounting for profitability analysis. Cost-type accounting separate different costs types such as labor, materials and depreciation. GPK also includes interest as a cost type. Each cost type is decomposed into variable and fixed costs along with the assignment of costs to cost centers. Cost type accounting leads to one of the most important elements of GPK; cost center accounting. Cost centers usually have one or a few cost driver and they determine the relationship between variable costs and the output of the cost center. This simplicity allows for detailed cost planning of each cost center with cost functions that describe the relationship between costs and output. Comparing planned and realized costs at the cost-center level provides early and detailed information about emerging problems. GPK uses two difference types of cost centers: primary and final cost centers. Primary cost centers cover activities that are far away from the manufacturing process while the final cost centers are closely connected to the manufacturing process. Only variable costs are charged to final cost center and only variable costs of the final cost center are charged to cost object in product costing. Product cost accounting assigns to products the cost of direct labor, direct material as well as the variable costs of the final cost centers. Only the variable costs of each product are shown in 3 Cooper, Robin, Kaplan, Robert S, “Profit Priorities from Activity-Based Costing,” Harvard Business Review, May-June 1991, p130-135. 4 Gunmther, Friedl, Ulrich-Hans, Kupper; Burkhard, Pedell, “Relevance Addes: Combining ABC with German Cost Accounting,” Strategic Finance; June 2005, Vol. 86 Issue 12, p56-61. product cost accounting. Fixed costs can also be allocated to products in a parallel calculation for mid-and long term proposes but this contradicts the basic principle of GPK. Fixed casts are allocated by a surcharge as a percentage of variance costs. The final element of GPK is contribution margin. The contribution margin of each product is obtained by subtracting variable costs from product revenues. This then supports short-term management decisions because the decisions are based on contribution margin rather than product costs. By subtracting the relevant fixed costs from the contribution margin, different contribution margins or different layers can be obtained. Example: If there are fixed Research and Development or Advertising costs for a small product groups, these costs are subtracted from the product group’s contribution margin. This type of layered contribution analysis supports short-term decision-making and gives recommendations for long term decisions. GPK is able to support many short-term management decisions such as optimal production plan, make-or-buy decisions, pricing decisions, or internal transfer pricing. Costs are highly transparent which helps influence the behavior of employees and identify potential weaknesses. These then are a major reason for the use of GPK in large industrial firms in German-speaking countries. GPK AND ABC COMPARED Since GPK applies the marginal costing principle and allocates only variable cost to products, this costing method provides information for short-term decisions. ABC, on the other hand, aims at allocating all the costs required to produce and market a product in the long run. It focuses on long term decisions such as product design and production and involves allocation of fixed costs that use assumptions about the proportion of costs that normally won’t be fulfilled which makes ABC less suited for short-term decision making. GPK allocates overhead costs on products via cost center and ABC does it via activities and processes, the underlying formal structure of cost pools and cost drivers is similar. Some companies use the cost center module of SAP for implementing ABC. This then shows that the difference between GPK and ABC aren’t about the structure of the system but involve the types and number of cost drivers and the allocation of fixed costs. Both systems use cost drivers in production-related areas to measure the performance of cost centers and their activities, but ABC employs nonoutput-related cost drivers such as product complexity and the number of product variants, which is suppose to improve the manufacturing design and reduce the number of parts used. ABC also uses cost driver to allocate total costs on products and GPK doesn’t because charging fixed costs to products isn’t in line with its principles. Both management accounting systems stress the issue of cost and profitability control through variance analysis. An important difference between GPK and ABC is the distinct focus of ABC on the process owner’s responsibility for their processes across cost centers and departments. This implies a horizontal, process orientation compared to GPK’s vertical functional one. There are advantages in combining GPK and ABC especially as the importance of indirect costs increases. A permanent ABC system that delivers detailed cost information of single activities on a monthly basis like GPK would be very expensive in most instances. An alternative solution for companies that are using GPK would be to define cost centers in indirect areas in order to improve planning and control of the principal activities costs. Another widely practiced alternative is to employ ABC on a case-by-case basis only, such as the development of new products. It is recognized that ABC compliments GPK in administrative and nondirect “cost centers.” It can be further argues that the discipline required to establish a cost center is identical to that required to establish an activity center in ABC. The important distinction source of long-term sustainment is the incorporation of a disciplines methodology into organizational measurement and management planning and control system. It is possible that incorporating the successful aspect of GPK with those of ABC combined with disciplined methodology and competent software will satisfy the needs of USA CFOs. IS THERE A FUTURE OF GERMAN COST ACCOUNTING IN THE USA? According to a survey, as many as eighty percent of American management accountants agree that their current methods of costing just aren’t good enough for current businesses, yet nothing is being done to overcome this deficiency.5 An American professor from Boise, Idaho visited many German-languages countries and came away with the impression that these countries are way ahead of the US in costing practices. While American controllers say they are dissatisfied with their cost accounting systems, most German controllers say they are highly satisfied with their cost accounting systems. If German systems are more advanced in terms of detail, precision, accuracy and control, why haven’t US businesses and accounting educators looked more favorable into the German GPK system? Are we prone to a “keep-it-simple” philosophy as the maintaining and feeding a GPK system takes a lot of time, or is it a matter of culture? Germans are known for precision engineering and they cannot fathom a costing system that isn’t terribly detailed, this isn’t an assumption that US companies are making. Although we say we have an inadequate costing system in the USA and the system is not meeting our needs, when asked if major improvement to the cost system are on the horizon, business and educators say “no.” US firms must decide to place a higher emphasis on management accounting than generally exists today. Long-term financial results will probably be improved by strong internal information and cost analysis. Many US firms have invested millions in integrated systems such as SAP R/3 yet don’t take full advantage of what these ERP systems can do for cost analysis, why? 5 Cheney, Glenn, “German Cost Accounting: Will it Work in American?,” Assurance; p14, Vol 19, No. 9 REFERENCE (1) Bursal, N. I. “German Cost Accounting Education and the Changing Manufacturing Environment” Management Accounting Research 3 (1992) (1): pp.1-24. (2) Cheney, Glenn, “German Cost Accounting: Will it Work in American?” Assurance Vol. 19, No 9, pp. 14. (3) Hoffjan, Andreas, “The Image of the Accountant in a German Context” Accounting and the Public Interest, Volume 4, 2004, pp. 62-887. (4) IMA Study. “German Cost Accounting Can Help Improve Financial Performance” IMAFunded Research, PR Newswire Association LLC. (Copyright 2005) (5) Kellermanns, Franz Willi, Islam, Majidul, “US and German Activity-Based Costing: A Critical Comparison and System Acceptability Propositions” Benchmarking: An International Journal, (2004) Vol.11 Issue l, pp 31-51, 21 (6) Krumwiede, Kip R. “Reward and Realities of German Cost Accounting” Strategic Finance (April 2005) Vol.86 Issue 10, pp. 27-34. (7) MacAurthur, John B; “Cultural Influences on German versus US Management Accounting Practices” Management Accounting Quarterly (Winter 2006) Vol.7 Issue 2, pp.10-16,7. (8) Matz, A, “Cost Accounting in German” EBSCO Publishing (Copyright 2002) pp.371-379. (9) Morgan, Malcolm J., Bork, Hans Peter “Is ABC Really a Need, Not an Option?” Management Accounting: Magazine for Chartered Management Accountant (September 1993) Vol.71 Issue 8, pp. 26, 2. (10) Schilbach, Thomas, “Cost Accounting in German” Management Accounting Research (September 1997) Vol. 8 Issue 3, pp.261-276,16. (11) Sharman, Paul A “Bring on German Cost Accounting,” Strategic Finance (December 2003) pp. 43-47. (12) Sharman, Paul A. and Vikas, Kurt “Lessons from German Cost Accounting Strategic Finance (December 2004) pp.28-35.