An Empirical Investigation of the Spillover Effects of Advertising and

advertisement

An Empirical Investigation of the Spillover Effects of Advertising and Sales Promotions in

Umbrella Branding

Author(s): Tülin Erdem and Baohong Sun

Source: Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 39, No. 4 (Nov., 2002), pp. 408-420

Published by: American Marketing Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1558554

Accessed: 28/01/2010 14:58

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ama.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Marketing Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Journal of Marketing Research.

http://www.jstor.org

TULINERDEMand BAOHONGSUN*

The authorsinvestigateand findevidencefor advertisingand sales

promotion spillover effects for umbrella brands in frequently purchased

packaged product categories. The authors also capture the impact of

advertising (as well as use experience) on both utilitymean and variance

across two categories. They show that variance of the random component of utility declines over time on the basis of advertising (and use

experience) in either category. This constitutes the first empirical evidence for the uncertainty-reducing role of advertising across categories

for umbrella brands.

An

of the

Spillover

Empirical Investigation

Sales

of Advertising and

Effects

Promotions in Umbrella

Branding

may be insufficientfor umbrellabrandingto generate savings in marketingcosts and enhance marketingproductivity

over time. To increasesavings in marketingcosts over time,

the marketingmix, such as advertising and sales promotions, must be more effective for umbrellabrandsthan for

other brands. For example, Tauber (1981) suggests that

umbrellabrandingcan create advertisingefficiencies. Leigh

(1984) finds some experimentalevidence for better recall

and recognition performance for umbrella branding than

other branding strategies. Yet there is surprisingly little

empirical work on advertisingand/or any other marketingmix synergies for umbrellabrands.

The objectives of this study are twofold. First, we test for

marketing-mixstrategyspillover effects of umbrellabrands

in frequently purchased packaged product categories. We

are especially interestedin testing for own- and cross-effects

of advertising,that is, whether advertising in one product

category affects sales in another product category for

umbrella brands. However, we investigate the crosscategory effects of all marketing-mix effects, including

price, coupon availability, display, and feature. Another

relatedobjective is to shed some light on the magnitudeof

any effects that may exist. We seek to answer the following

questions: (1) What is the impact of the cross-effects on

sales? (2) How large are the cross-effects of the marketing

mix elements in relationto the own-effects? and (3) Which

marketing-mix elements seem to reveal higher crosseffects?

Second, we explore the dynamics behind the advertising

spillover effects. Similar to use experience, advertising

spillovereffects occur for variousreasons,but they may also

transpirebecause of the uncertaintyreduction.More specifically, we examine whetherthere is a reductionin consumer

uncertainty in one category due to advertising of the

Many companies widely practice umbrella branding.

Also, a fair amount of managerial research argues that

umbrellabrandinggeneratessavings in branddevelopment

and marketing costs over time (e.g., Lane and Jacobson

1995; Tauber 1981, 1988) and enhances marketingproductivity (e.g., Rangaswamy,Burke, and Oliver 1993).

Wernerfelt(1988) has shown analytically that a multiproductfirm can use its brandname as a bond for quality

when it introduces a new-experience product. Umbrella

brandingis posited to both increaseexpected quality(Wernerfelt 1988) and reduce consumer risk (Montgomery and

Wernerfelt1992). Consumers'use experience in one product category needs to affect their perceptionsof quality in

anotherfor umbrellabrandingto serve as a credible signal

of a new-experienceproduct'squality,becausea false signal

would be costly if the quality of the extension turnedout to

be poor. Experimentalresearch has shown some evidence

that the parent brand'sperceived quality affects the extension evaluations (Aaker and Keller 1990) and vice versa,

which indicatesthatbrandequity dilutionmay occur (Loken

and RoedderJohn 1993).

Although the cross-categorylearningeffects for umbrella

brandsare a necessary condition for umbrellabrandingto

functionas a signal (Erdem 1998), the learningeffects alone

*TulinErdem is an associate professor,Universityof California,Berkeley (e-mail: erdem@haas.berkeley.edu).Baohong Sun is an assistant professor, Kenan-Flagler Business School, University of North Carolina,

Chapel Hill (e-mail: sunb@bschool.unc.edu).The authorsthankthe three

anonymous JMR reviewers for their constructive feedback. The authors

also thank Andrew Ainslie and Michael Keane for their suggestions in

regardto the updating mechanism of the stochastic component of utility

employed in this article. This researchwas supportedby NationalScience

FoundationgrantSBR-9812()67 grantedto Tiilin Erdelm.

Joi)rltl

o1!f Marketing Research

Vol. XXXIX (Novcelbhcr 200(2), 4()8-420

40()

409

Advertising and Sales Promotions in Umbrella Branding

umbrellabrandin anothercategoryover time. If uncertainty

exists and advertisingreduces consumer uncertaintyabout

products,advertisingis expected to shift both utility mean

and variance.To model and test for both utility mean- and

utility variance-shiftingcross-effects of use experience and

advertising,we develop a novel and parsimoniousapproach.

Our approachenables us to test whether there is any evidence for the uncertainty-reducing

role of advertisingacross

categories.

We use ACNielsen scanner panel data on two categories-toothpaste and toothbrushes-to test for marketingmix synergies for umbrellabrands.For the first time in the

literature,on the basis of our analysis of revealedpreference

data, we find evidence for advertisingspillover effects for

umbrellabrands.Furthermore,we find that advertising(as

well as use experience) in one category serves as a mechanism of reducing uncertainty in the other category for

umbrellabrands.In addition, our results indicate that there

are spillover effects of price, coupon availability,and display. Feature cross-effects exist only in the toothbrush

category.

The rest of the article is organizedas follows: In the first

section, we briefly discuss the relevantliterature.In the second section, we outline the proposedmodel and the estimation method. In the third section, we briefly describe the

data. We then outline the results and conclude the article

with implicationsand a discussion of furtherresearch.

LITERATURE

REVIEW

Previous researchin marketinghas studied the effects of

sales promotionsacross categories for complementaryand

substitute products (e.g., Mulhern and Leone 1991) and

multicategory choices (e.g., Bell and Lattin 1998; Manchanda,Ansari,and Gupta 1999). A separatestreamof literature focuses on cross-categorytraitsof consumerbehavior

and finds that consumer price sensitivities (Ainslie and

Rossi 1998; Erdem 1998) or sensitivities to state dependence (Erdem 1998; Seetharaman,Ainslie, and Chintagunta

1999) can be correlatedacross categories.

However, there is surprisingly little published research

with respect to cross-categoryeffects in choice for umbrella

brands. Erdem and Winer (1999) have shown that brand

preferencescan be correlatedacross categoriesfor umbrella

brands.Erdem (1998) has studied how consumers'experience in one category may affect theirquality perceptionsin

another category for umbrella brands. In a two-category

context, Erdem has shown that consumer mean quality

beliefs, as well as the varianceof these quality beliefs, may

be updated through experience in either category for

umbrella brands.Thus, Erdem studied only cross-category

use experience effects.

Specifically, Erdem(1998) does not study any promotion

or advertising effects, neither own-category nor crosscategory, which is the topic of this article. Therefore,she

does not study and answerany questionsaboutthe existence

and magnitude of cross-advertisingand promotioneffects

for umbrellabrands.Furthermore,her model does not incorporatepurchaseincidenceand coincidence in choice, thatis,

the possibility that the stochastic component of the utility

function could be correlatedacross categories. In addition,

Erdem'sapproachonly allows for use experienceeffects due

to learning, whereas the approach we take in this article

allows for both learning effects and other sources through

which use experience may affect currentchoices. Furthermore, the approachErdemtakesto incorporatethe impactof

use experienceon utility varianceis difficult to apply to settings in which cross-categoryvariancereductioneffects can

be due to other variablesas well (such as advertising).The

approachtaken in this articleprovidesa more parsimonious

and novel way to incorporatesuch effects. Finally,we allow

for more complex heterogeneity structuresin this article

than Erdemdoes.

Manchanda,Ansari,and Gupta(2000) also find some preliminaryevidence for spillover effects in store promotional

activity for umbrella brands;however, they have not analyzed advertising and they have not allowed for choice

dynamics.

THEMODEL

UtilitySpecification

Considera set of consumersI = {ili = 1, 2, ..., I that,on

each purchaseoccasion, makes purchasesfrom none, one, or

both of two distinct productcategories m = 1, 2, where I is

the numberof consumers.A nonemptysubset, but not necessarily all, of these consumersmakes purchasesfrom both

of the categories. Suppose that for both productcategories,

the purchasesof the consumersare observedover the period

T = tit = 1, 2, ..., T}, whereT is the time span of the period

and t denotes the week. Let J = (jlj = 1, 2, ... J} be the set

of brand options available, where j = 1 ..., J brands are

available in at least one of the two categories and J is the

numberof brands.Note that we set j = 0 to indicatethe nopurchaseoption (choice).

Let Knj,m = 1, 2, be an indicatorvariablesuch thatK,-j =

I if brandj is available in category m, and K,n.= 0 otherwise. Also let Dmijt,m = 1, 2, be an indicatorvariablesuch

that if consumeri purchasesbrandj at time t in categorym,

D,iji = 1, and D,,jt = 0 otherwise.Finally,denote the utility

consumeri derives from purchasingbrandj in categorym at

time (week) t by Uijt, which is postulatedto be

(1)

Umijt

= (tmij +

,miPRmiit

+ ymiADmiit + XmiDlSPmijt

+ TmiFEATmijt + OmiCAVmijt+

KmiUEmijt

+ K3-m,j(miPR3-

m,i,j,t + tmiAD3-m,ij,t

+ lmiDISP3 m,i,j,t + VmiFEAT3,- ,i,j,t

+ ,nmiCAV3

- m,i,j,t +(On, i UE3 m,i,j,t) + ?Emijt,

where PR,,ijtis the price paid for brandj in category m by

consumer i at t, AD,n,jtis the advertisingstock variablefor

consumer i with respect to brand j in category m at t,

DISP,nijtis the display dummy, FEAT,nitis the in-store ad

dummy, CAV,ijt is the coupon availability variable, and

UE,nijtis the use experience of brandj in category m consumer i has at t. Equation 1 suggests that if brandj is available in both categories, the utility of purchasingbrandj in

one of the categories will also depend on the price, coupon

availability,advertising,display,feature,and use experience

associated with the same brandname in the othercategory.

INote that in Equation I, cross-effects are specified for umbrellabrands

only. In the empirical analysis, to ensure that the effects exist for only

umbrella,we also tested whethersuch effects exist for otherbrandsas well,

and we did not find evidence for such effects.

410

JOURNAL OF MARKETINGRESEARCH, NOVEMBER 2002

The parametersin Equation I are as follows: a,ij is the

consumer- and brand-specificconstant (brand preference),

and imi is the consumer-specific price coefficient. Moreover, Ymi,Xni, tmi, Omi, and Kmi are the consumer-specific

advertising, display, feature, coupon, and use experience

coefficients in category m (we label these own-effects

response coefficients), whereas, ini, tmi,

mi, Vmi, cmi, and

are the price, advertising,display,feature,coupon availability, and use experience coefficients of the price, advertising, display, feature, and use experience variablesin the

other category, respectively (we label these cross-effects

response coefficients). Similar to Erdemand Keane (1996),

we specify i's utility from not purchasingany brandin category m at t as2

()mi

(2)

Umi0t = (mo + TRENDmt + emot,

where TRENDMis the time trendcoefficient, and for identification purposeswe set

(3)

(mO

= 0,

m = 1,2.

The use experience variable, UE,ijt, in Equation I is

defined as the exponentiallysmoothed weighted averageof

past purchases, as in Guadagni and Little's (1983) brand

loyalty variable. Its decay parameteris denoted by DUm.

Similarly,AD,nijtis defined as the exponentially smoothed

weighted average of past aggregate gross rating points

(GRPs).3 Its decay parameter is denoted by DAm. The

AD,,,ijtis updatedon a weekly basis. Note thaty,i (andr1mi),

the coefficient on the advertising stock variable, embeds

both a consumer'stelevision commercialviewing habitsand

responsivenessto the advertisements,conditionalon having

seen them. Because advertisingeffectiveness in the context

of television advertisementsdependson television and commercial viewing habitsof consumers,we can justify thaty,,

(and tl,) representsadvertisingresponsivenessat the individual level.4

We define the DISP variablesuch that DISP,nij,= I if a

display is availablefor brandj in categorym in the store that

consumer i visits at t, whereas DISP,,ijt= 0 otherwise.Similarly,we define the FEATvariablesuch thatFEAT,ijt= 1 if

a feature is available for brandj in category m in the store

= 0 otherwise.

that consumer i visits at t, whereasFEAT,nijt

of

is

the

value

the

store's

and manaverage

Finally, CAV,,ijt

2Similarto Erdem and Keane (1996), our purposeis to control for purchase incidence ratherthanexplicitly model purchaseincidence decisions.

3An alternativeto GRP data is television exposure data;however,television exposure data are not available because ACNielsen discontinuedthe

collection of such data in the early 1990s. Televisionexposuredatahave the

advantageof havingthe estimatedadvertisingcoefficient reflectadvertising

responsivenessonly because the advertisingvariableitself will capturethe

television/commercial viewing habits. However, the television exposure

data are noisy as well, because we only knew that the television was tuned

to that channel duringthe airingof a particularcommercial.One advantage

of the GRP data, in contrast,is that GRP is underthe direct control of the

firm whereas television exposure is not. Therefore, firms are more interested in models that use GRP data (Abe 1997). Finally, Tellis and Weiss

(1995) find that advertising effectiveness results are not sensitive to the

types of advertisingmeasures.

4Wealso have GRP data for different"dayparts"(e.g., primetime versus

late morning).When we used these dataandestimatedEquationI with separate coefficients for each daypart,we obtained largeradvertisingcoefficients for certain daypartsthan others, as we would expect, but the main

results are the salmewhetherthe daypall data are used or not.

ufacturer'scoupons availablefor brandj in categorym in the

store thatconsumeri visits at t. It includes the zero value for

nonavailable coupons (Keane 1997b). We introduce this

variableto avoid the endogeneityproblemcaused by including coupons redeemedin the utility specification.Last, Emijt

in Equation 1 denotes the time-varyingstochastic component of utility that is knownby the consumerbutnot observable by the analyst.

We should note that the cross-effects specified in Equation 1 may exist for several reasons. First, price cuts,

coupons, advertising,displays, and featuresin one category

may remind the consumer about the umbrella brand and

thereforeincreasethe likelihoodof theirchoosing thatbrand

in anothercategory, conditional on productcategory decision. In the case of promotionaltools such as displays, the

promotionof the umbrellabrandin one category may help

promote the umbrella brand in consumers' consideration

sets in the second category, in which the brandis not promoted, as well. Advertisingcan be expectedto increasegeneral brandawareness of individualproductsthat share the

same brand name. Cross-category use experience effects

may be due to habit formation.

Second, the effects of use experience and advertisingon

consumeruncertaintymay cause use experienceand advertising spillover effects. If use experience affects quality

beliefs, both the mean and variance of these beliefs may

change on the basis of use experience. Therefore, if use

experienceaffects consumeruncertainty,we shouldexpect it

to affect both the utility mean and variance in a reducedform model. The same rationale holds for advertising.

Erdemand Keane (1996) have shown that in the context of

one category, both use experience and advertising affect

both mean and varianceof qualityperceptions.Therefore,if

advertisingspillover effects are partly due to the effect of

advertisingon consumer uncertainty,we should expect utility variance(that is, the varianceof the randomcomponent

of utility) to decline over time on the basis o' advertising.

We capture these utility variance effects by adopting a

novel approach.Specifically,we allow for not only the "random" components of utility to be correlatedacross categories but also the variancesof the randomcomponentsfor

umbrellabrandsto be updatedon the basis of past purchases

and advertising associated with umbrella brands in either

category.We cover this issue in more detail subsequently.It

may suffice to state that we attemptto capturethe effect of

use experience and advertisingas a shifter of both utility

mean and variance; the latter effect should occur mainly

because the consumer uncertaintydecreases over time on

the basis of past purchasesand advertising.

Heterogeneity Specification

It is well established that not accounting for unobserved

heterogeneitycan bias parameterestimates(Heckman 1981;

Rossi and Allenby 1993). In this article, we account for

unobservedheterogeneityas well. To do so, we assume that

brand preferences for each category A,mi= (a,n,i, aii2, ..

a1ij)T; own-effects response coefficients B,,i =(P:- i, ni,

, lmi, K,lni)T;and cross-effects response coefficients

mi'

mti

t li,

Cmi = (i,

lli, Vm,I,

i O,,1i)T, m = i, 2, where the

superscriptT denotes the transpose,are normallydistributed

with the following mean vectorand covariancematrix:

411

Advertising and Sales Promotions in Umbrella Branding

-A7 ii

-Al-

Bli

B,

Ci

C,i

(4)

A2i

to be more advertisingsensitive than the averageconsumer

in the toothpaste category. The corresponding crosscategorycorrelationscan be calculatedfrom the covariance

matrixn. We denotethese cross-categorycorrelationsby A.6

- Nc

A2

B2i

B2

-C2i

-C2.

Choice Probabilities

Let us rewriteEquation1 for each categorym, wherem =

1, 2, as

-'

-E;A

"A1B,

YBB

]EBI

"AlC,

nBC

B11C,

?C|

!AIB2

HAB

IIAIC,

nAC2

BBIA2

!CiA2

nClB

!BiB,

nBC

-CC2

nAA2

nBB2

I"AB2

nciA2

?A2

"CIB

A,B2

mmijt

Vmijt

+

?mijt'

A,C2

nBiA,

nA2C2

(5)

i"A2B2

EB2

A 2C2

nB,C2

nCC2

r[

A2C2

A2C2

ZC2

The vectors Al, B , Ci are the means in Category I and

the vectors A2, B2, C2 are the means in Category 2. The

block diagonal matrices EAI, E?B,ICI, IA2, ?B2, and ?C2

are the covariancematricesof A l, Bij, Cli, A2i,B2i,and C2i,

respectively.The diagonal elements ofA AI, B 1,ECi, IA2,

ZB2, and ZC2themselves containthe variancesof the corresponding heterogeneity distributions. Finally, F! are the

appropriatecovariancematrices.

Within-CategoryCorrelations

Given the large numberof covariancesto be estimatedas

shown in Equation4, we allow only a subsetof these covariances to be nonzero for parsimony.5We allow heterogeneity

in all brand-specific constants and allow own and cross

marketing-mix response and use experience coefficients;

however,we estimate and reportin the "Results"section of

the article only the following covariances (correlations)

among the heterogeneity distributions: (I) correlations

among the brand specific constants and price (as well as

advertising)sensitivities, (2) pairwise correlationsbetween

own price (and advertising) sensitivities and all other

marketing-mixsensitivities (e.g., display), and (3) pairwise

correlationsbetween own price (and advertising)sensitivities and use experience.

Cross-CategoryCorrelations

Ainslie and Rossi (1998) suggest that consumersensitivities to marketing variables (own-effects of the marketing

mix in our model) may be correlated across categories.

Therefore, a person who is more price sensitive than the

average consumer in one category can be also more price

sensitive than the average consumer in another category.

Therefore,we also estimate nBI B2 (the covariancematrixof

Bl and B2). This means that we permit consumer price,

advertising, display, feature, coupon, and use experience

sensitivities to covary across the two categories. For example, a consumer who is more advertisingsensitive than the

averageconsumer in the toothbrushcategory may also tend

sHowever, in the empirical analysis, we tested the sensitivity of our

results to the assumptions made about covariance structureby allowing

more covariances(correlations)to be nonzero. For example, we estimated

the covariancesbetween brand-specificconstants,a few covariancesamong

the cross-responsecoefficients, and so forth,but these did not improvethe

model fit significantly and did not change the parameterestimiates.

whereVmijtis the "deterministic"partof the utility.

Let 0 denote the vector of parameters(Al, A2, BI, B2, Cl,

C2, d(ZAI), d(EA2), d(ZBI), d(IB2), d(ECI), d(IC2),

w(n))T. The vectors d(EAI), d(AA2), d(ECI), and d(IC2)

containthe diagonalelements of the correspondingmatrices

(i.e., the variances of the heterogeneity distributions of

brandpreferencesand cross-effects response coefficients).

The vectors d(EBi) and d(EB2) contain the diagonal elements(variancesof own-effects responsecoefficients)of the

correspondingmatrices, as well as the off-diagonal elements, or covariances, that we allowed to be nonzero.

Finally,the vector w(n) contains the covariancesamong the

brand-specificconstantsand advertisingand price sensitivities, as well as cross-categorycovariancesto be estimated.

Note that though we used the covariancematricesin defining the parametervectorfor notationalconvenience,we estimate the correspondingstandarddeviationsand correlations

introduced previously, instead of the variances and

covariances.

Recall thatall coefficients in EquationI are allowed to be

heterogeneousacross consumers,and their distributionsare

given in Equation4. Let (pidenote the multivariatestandard

normalvectorthatgeneratesthese coefficients.To be able to

write down the choice probabilities,we need to specify a

distribution for Emijt

We assume that ?,mijtj e J is given by

(6)

?miit

= Ymiit

-Et[Ymiit],

where y,ijt is the generator of ?,ijt, whose prior distribution

is

(7)

Y,io

Y2ij0_

N([o]P p I1

,

Note that Et[.] indicates expectation conditional on the

informationat time t. Equations 6 and 7 indicate that the

means of the randomcomponentsare always zero, whereas

the assumption is that the initial variancesare one and the

initial covariancebetween the randomcomponentsis p.

A parsimonious and new way of capturing the utility

variance-shiftingrole of use experienceandadvertisingis to

allow the initial utility variance,which we set to unity,to be

updatedconditionalon past purchases.Neitheradvertising's

6Finally,note that we adopt the recent classical inferencetechniquesto

model and estimate unobserved heterogeneity. An alternative approach

would have been Bayesiantechniques(e.g., Rossi, McCulloch,andAllenby

1996). However, the main advantageof such techniques is the ability to

providehousehold-levelparameterestimates, which is particularlyuseful if

the research objective includes micromarketingimplications, which is

beyond the scope of this article.

412

JOURNAL OF MARKETINGRESEARCH, NOVEMBER 2002

impact on the consumer utility mean nor its impact on the

consumer utility variance across categories for umbrella

brandshas been empiricallyverified in previouswork.

To capturethe effects of both use experience and advertising on the varianceof the randomcomponent,thatis, utility variance,let the informationobtainedby consumeri by

purchasingbrandj before time t fromcategorym be denoted

by xmijt.This informationcan be about attributes,including

quality,or match informationbetween consumertastes and

productofferings and the like, which are not observedby the

analyst. Let x,ijt be given by

(8)

Xmijt

=

Ymijt

+

6mijt'

where 6i.jt is an i.i.d. random error term that reflects the

level of noise in the informationobtained.We suppose that

(9)

-

,mi.t

N(O, o62).

Note that additionalinformationcomes from weekly advertisements. Denoting this informationwith z,ijt , we let

(10)

mijt

=

Ymijt

+ 1

Given these, we then assume that the randomcomponent

of utility is updated according to Bayesian updatingrules

and invoke the Kalmanfilter for updatingthe distributionof

Y,nijtand therefore of ?,j1.t There is no updatingfor j = 0,

which correspondsto no purchase.To derivethe Kalmanfilter, we regress

Ymiit- Et- I[Ymiit]

(14)

b2mijt

am,,

m,i,j,t-

b3mijt

2

b

12

_ 4mijt

i,3-m

- Et(

,mi,2 = E{[Ymijt

12i.jt=

_

12,i,j,t-I

m = 1,2

t)]2}

E {[Yijt- Et (ylijt)][Y2ijt - Et(Y2ijt)]}

Note that the precedingequationssuggest that the higher

the precisionof informationfromuse experience(l/(' n)and

advertising (I/'2 n) are (or the lower the use experience

variability, 'n,, and advertising variability,oG2, are), the

more consumerswill update.

Given Equations 12 to 14, the distributionof ?1ijt, m = I,

2 at time t is given by

2 0

-.

O _101

(T 12ijt

ijt

j=

1,2,...,J.

11t2

02i 12ijt

We then can write the choice probabilitiesconditional on 0

and (pias

(16)

Probjt(D!ijt

=

1;p)=

= 1,Dt

)

tjk(0,(Pi),

where q)tjk(-)is the appropriatecumulativedistributionfunction whose probabilitydistributionfunction is determined

from Equation 15. Note that this is a 2J + 2 dimensional

integral.Therefore,the probabilityof consumer(household)

i makingthe sequenceof purchasesgiven by D,,,jt, m = 1, 2,

j = 0, , ..., J, t = 1, ..., Ti, conditionalon 0 and (pi,is

T

(17)

J

J

Prob (0, i) = n

DlijtD2Ijtt ( pi).

t=l j =O k=0

m = 1, 2

Xmijt- Et_ I[xmijt]and Zmijt- Et_ i[Zmijt],

by suppressing the intercept,and we obtain the following

updatingformulasfor the expectations:

=

Et[Ymiit] Et _[Ymijt] + blmijt{xmijt Et,- [mijt]}

+

- Et

+ b4mijt{z3 -m,i,j,t

[nmi,j,t ])

Et[Z3

m,i,j, t]'

where bk,,lit, k = 1, 2 and m = 1, 2 are solved from

2

2

, t- I + 6m

-

Dm,i,jt-j

D3- m,i,j,t - 1o12,i,j,t -I

2

DDm i jt - I(Y

m,i,j,t - I

I

Dm,i,j,t 11(12,i,j,t

(13)

D

- Im,,j,

-

CY- 11,i,,-- II..

IniJDi.,t- I 12I,i,j,t

2 ++ 03

G

i,,t

D3 1- m i.j.t - lI312,i,,jt

D3 -m.i.,l t -

I<3-12,i,

-D0II

,3 - n

12Y

2

2

m,i,j,t - I

ni, j,t - I

-

0 2, i,j.t -

D

D3-m,i,t

j,i

2

j,- 2 I2 ++ I

j.t -I

Integratingover(Qi,we obtain

(18)

Probi(0) =

I Prob(0,(p )f/(pi 0)d(pi,

n

E - I[Y3 m,i,j,t 1)

b2mijt {x3- m,i,j,t

+b3mijt{Zm,ij,t

D

Dm,i,j,t-

and with Equation 12, the updatingformulas for the variances are obtainedfrom

on

(12)

2+

im,i,j,t - I

3-m,i,j,t - 112,i,j,t- I

"bimijt

-1

2

03-m,i,j,t-

mijt'

N(O, m 2)

rmiit

D3-m,i,j,t - (3-m,i,j,t

012,i,j,t - I

-c2ij'tL[2ijt

where rijtm is an i.i.d. randomerror term that reflects the

level of noise in the informationfrom the advertisement.It

is given by

(11)

m,i,j,t - 1 12,i,j,t - I

m

I

where Q2is the domain of the integration,whereasf((p10) is

the multinomialprobabilitydistributionfunctionfor pi,conditional on 0.

Thus, we estimate a multivariate multinomial probit

model, which has been adopted in some recent articles in

marketing as well (e.g., Manchanda,Ansari, and Gupta

1999). This model allows randomcomponents to be correlated across the m categories, which Manchanda,Ansari,

and Gupta label as "co-incidence."Thus, factors that are

unobservedby the analystbut knownby the consumercould

be correlatedacrosscategories.However,for the first time in

the economics and marketingliterature,we also incorporate

into this model a process by which the varianceof the random component (as well as the covariance of this component across the m categories) is updatedover time, on the

basis of past purchasesof the consumersand past advertisement. The extent of the updatingis determinedby l/o'1n in

the case of use experienceand by 1/o', in the case of adver-

413

Advertising and Sales Promotions in Umbrella Branding

tising; that is, the more precise the informationsource is, the

more updatingthere will be.

Given Equation18, the log-likelihoodfunctionto be maximized is

I

(19)

LogL(O)= Xln[Probi(0)],

i=l

Note that the calculationof Probi(O)in Equation19 requires

the evaluation of multiple integrals,which in turn requires

Monte Carlo simulation techniques. We use a probability

simulatoras the Monte Carlo method (Geweke 1991; Hajivassiliou, McFadden,and Ruud 1994; Keane 1990, 1994).

As our estimation method, we adopt the method of simulated moments (MSM) first developed by McFadden(1989)

and extended by Keane (1990).

EMPIRICALANALYSIS

Data

The models are estimatedon scannerpanel data provided

by ACNielsen for toothpasteand toothbrushes.Given new

productfeatureintroductionsand the existence of long-term

experience attributes(e.g., cavity-fightingpower of a toothpaste), quality uncertaintymay exist even in the relatively

matureproductcategoriestypically studiedin scannerpanel

research (Erdem and Keane 1996). Also note that because

most frequentlypurchasedproductcategories are not highinvolvementgoods, consumerstypicallyrely more on brand

names and advertisingthan on active search to resolve any

quality uncertainty.

The panels cover 157 weeks from the end of 1991 to the

end of 1994. The data sets includehouseholdsfrom two test

markets in Chicago and Atlanta.We use the Chicago panel

for model calibration.We use the Atlanta panel to assess

out-of-sample fit (i.e., the predictivevalidityof the models).

The analysis includes four brandsin each category.In both

the calibration(Chicago) and the prediction(Atlanta)panel,

we randomlydraw the panel members from the sample of

households that do not buy multiple brandsin a given category on the same purchaseoccasion.

The first two brands(Brand 1 and Brand2) are available

in both categories. Table I providessummarystatistics.The

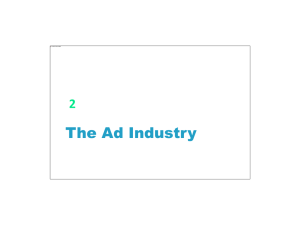

weekly GRPs are plotted in Figure 1. The price used in the

study is the price paid without any coupons. Using a price

value net of coupons introducesa seriousendogeneityproblem; therefore, we model coupon effects by using the

coupon availabilitymeasurewe have defined previously.

ParameterEstimatesand Goodnessof Fit

We estimatedthe model describedpreviouslyand various

nested models. Table 2 reports the results for five nested

models and the full model. The sixth nested model has the

multivariateprobit specification with correlatederrorsand

allows for updatingerrorson the basis of past purchasesbut

does not allow the errorsto be updatedon the basis of past

advertising.The fourth nested model (NM4) has the multivariate multinomial probit specification with correlated

errorsacross the categories but does not allow for updating

errorson the basis of purchasesand advertising.The third

nested model (NM3) allows for neitherupdatingnor correlated errors across the two categories. The second nested

model (NM2) is similar to NM3 but does not allow for use

experience, price, coupon availability,advertising,display,

and featurein one category to affect the utility of the other

category.Finally,the first nested model (NM ) is similarto

NM2 except that heterogeneitydistributionsare assumedto

be independentacross the two categories. Both in-sample

and out-of-sample, the full model fits the data statistically

betterthan all other nested models. Therefore,we focus on

the parameterestimates obtained by estimating the full

model.

In a given category,the results indicatethatcoupon availability,advertising,displays, features,and use experienceall

have significant, positive effects on consumer utility,

whereasprice has the expected negativeeffect. Thereis significant heterogeneityin consumer tastes and responses to

use experienceand marketing-mixvariables.The time trend

in the no-purchasespecification is statisticallyinsignificant.

Given the objectives of this article, the importantparameter estimates are associated with the cross-effects of

marketing-mixvariables(and use experience),as well as the

cross-categoryparametersthat govern the process of updating the utility error term variance over time through use

experience and advertising.These parameterestimates are

markedin bold in Table 3.

We find thatuse experience in one categoryhas a positive

impact on brandchoice probabilitiesin the other category

Table 1

SUMMARYSTATISTICS

Brand Name

MarketShare

AveragePrice"

Average

GRP

Frequencyof Display

Frequencyof Feature

AverageCouponti

Toothpaste

Brand 1

Brand2

Brand3

Brand4

31.3%

20.0%

10.6%

9.5% (71.4%)

$1.81

$1.87

$1.81

$2.67

13.54

27.07

0

0

2.0%

1.6%

1.4%

1.2%

2.9%

2.8%

3.2%

1.8%

$.15

$18

$.23

$.23

Toothbrush

Brand 1

Brand2

Brand5

Brand6

10.2%

21.8%

19.4%

17.3%(68.7%)

$2.36

$1.99

$2.36

$1.96

12.62

19.75

22.84

0

1.2%

1.1%

.6%

.7%

2.6%

3.1%

3.2%

3.3%

$23

$19

$.27

$19

t'Weightedaverage price per 50)ounces for toothpaste.Weightedaverageprice per unit for toothhrush.

'Average nonzero coupon value of toothpaslenormalizedat 50()ounces. Averagenolnero coupon value of toothbrushper unil.

:

JOURNAL OF MARKETINGRESEARCH, NOVEMBER 2002

414

Figure 1

WEEKLY

GRPs

Plot of Weekly GRP for Toothpaste

100

'I

Xl

,

Week

Brand 1

------

Brand 2 [

Plot of Weekly GRP for Toothbrush

100

a-

c:

50

o .

o

1

1

,iI' . .

9

.,

*

/ '

,...

, i,,f T i (, ? 1nr

1

,,,

^'.a,.r, A 3,

.

17

25

33

41

49

57

-

65

81 89

73

r ir

97

1 11 11I i T

tTIIT

1 1l

105 113 121 129 137 145 153

Week

Brand 1 ------

Brand2

Brand5

Table 2

MODELSELECTION

In-Sample(Chicago)

-LL

AIC

NMI

NM2

NM3

NM4

NM5

FM

21323.4

21417.4

20731.6

20831.6

20212.5

20336.5

20101.2

20226.2

19510.4

19637.4

18925.3

19054.3

21839.0

13260.5

21280.1

12936.2

20892.3

12712.2

122179.6

20786.9

12367.5 2592.7

20208.0

19633.9

Out-of-Sample (Atlanta)h^

BIC

-LL

"Numberof observations= 59,032 (includingno purchases),numberof households(hhs) = 376; 167 hhs made621 purchasesof toothbrush;345 hhs made

2880 purchasesof toothpaste; 136 hhs purchasedboth toothbrushand toothpaste.

hNumberof observations= 30,301 (includingno purchases),numberof hhs = 193; 92 hhs made 198 purchasesof toothbrush;186 hhs made912 purchases

of toothpaste;85 hhs purchasedboth toothbrushand toothpaste.

Notes: LL = log likelihood;AIC = Akaike informationcriterion;BIC = Bayesian infornation criterion.

for umbrella brands. We also find statistically significant

cross-categoryeffects of advertisingin both categories.Furthermore,we find evidence thatcoupon availabilityand display (significantat the p <. 10 level) in the toothbrushcategory affects consumer utility in toothpaste positively for

umbrellabrands.Coupon availability,display,and featurein

the toothpastecategory affect consumerutility in the toothbrushcategory positively as well. Finally,prices have negative cross-category effects in both categories. Therefore, a

price cut in one category for an umbrellabrand increases

consumer utilities and thus the choice probabilitiesfor that

brandin the other category.

Turningour attention to the random component of the

consumerutility and the process of utility varianceupdating

based on use experience and advertising,we find the following results: Random components are correlatedacross

the two categories.Recall that we estimatedan initialcorrelation betweenthe randomcomponents,which we find to be

positive and significant. However, our results indicate that

both osa and oln are statisticallysignificant in both categories. Therefore,dependingon the degree of the precision

of information (i.e., 1/o,Smor I/oG,n), the variance and

covarianceo' randomcomponentsacross the two categories

are updatedwith use experienceand advertising.This result

415

Advertisingand Sales Promotionsin UmbrellaBranding

Table3

ESTIMATION

MODEL

Parameters

Brand I

Brand2

Brand3 (5)a

Brand4 (6)

No purchaseh

Brand I

Brand2

Brand3 (5)

Brand4 (6)

No purchase

Brandspecific constantsan,j

Standarddeviationof brandspecific constant nctmj

Trend,,

Mean price coefficient P1,

Standarddeviationof the price randomeffect 7p,.

Mean coupon coefficient on

Standarddeviationof the coupon randomeffect (o,m

Mean ad coefficient y,,

Standarddeviationof the ad randomeffect (9ml

Mean display coefficient kn

Standarddeviationof the display randomeffect o(,,

Mean featurecoefficient x,,

Standarddeviationof the featurerandomeffect on

Mean use experience coefficient Km

Standarddeviationof the use experience randomeffect (oc

Mean cross-price coefficient 3 - m

Standard deviation of the cross-price random effect ag_ m

Mean cross-coupon coefficient 3 - m

Standard deviation of the cross-coupon random effect 3 _ m

Mean cross-ad coefficient 13 m

Standard deviation of the cross-ad random effect a3 - m

Mean cross-display coefficient 13 _ m

Standard deviation of the cross-display random effect 3-_m

Mean cross-feature coefficient V3_ m

Standard deviation of the cross-feature random effect av3 - n

Mean cross-use experience coefficient (03_ m

Standard deviation of the cross-use experience random effect o

Use experience smoothing parameterDUM

Media smoothing parameterDA,

Correlationbetween constanttelrmsand price pa,i,p,,

_-m

Correlationbetween constantterms and advertisingPamrn,

Correlationbetween price and ad coefficients pi,,,ny

Correlationbetween price and display coefficients pp,,lmX

Correlationbetween price and featurecoefficients Ppi,Tm

Correlationbetween price and coupon coefficient Ppnmom

Correlationbetween price and use experience coefficients P,c;m

Correlationbetween ad and display coefficients Pyv.m

Correlationbetween ad and featurecoefficients Ppini

Correlationbetween ad and coupon coefficients P,nl,9

Correlationbetween ad and use experience coefficients Py,,n,

Cross-categorycorrelationbetween price coefficients AIP2

Cross-categorycorrelationbetween ad coefficients AyI.2

Cross-categorycorrelationbetween display coefficients AX.i2

Cross-categorycorrelationbetween featurecoefficients At,t2

Cross-categorycorrelationbetween coupon coefficients A0102

Cross-categorycorrelationbetween use experience coefficients A,i,e2

Cross-category correlation between error terms p (in the initial period)

Advertising variability o%for toothbrush

Advertising variability a6 for toothpaste

for toothbrush

Experience variability CYn

Experience variability Oc for toothpaste

Brand I

Brand2

Brand3 (5)

Brand4 (6)

Brand I

Brand2

Brand3 (5)

Brand4 (6)

Toothpaste(m = I)

Toothbrush(m = 2)

-2.07(.19)

-2.54(.28)

-3.29(.22)

-3.31(.17)

0

1.51(.34)

1.35(.20)

1.00(.22)

.58(. Il)

0

.015(2.53)

.010(2.57)

-1.21(.18)

.56(.16)

.82(.12)

.55(.16)

.12(.05)

.05(.02)

1.49(.26)

1.20(.25)

1.09(.40)

.82(.43)

2.74(.33)

1.86(.30)

-.11(.04)

.08(.13)

.45(.18)

.23(.09)

.011(.005)

.008(.005)

.097(.055)

.091(2.58)

.132(.083)

.085(.044)

.82(.25)

.45(.45)

.78(.12)

.28(.10)

.15(.09)

.19(.19)

.07(.11)

-.29(.05)

.12(.04)

.09(.05)

.06(.03)

.07(.05)

-.17(.08)

-.25(.10)

-.17(.07)

-.18(.07)

-.21(.09)

.11(.06)

.08(.04)

.16(.07)

.27(.12)

-3.77(.32)

-.26(.10)

-.86(.21)

-1.03(.26)

0

1.02(.18)

.47(.19)

.23(. 11)

.11(.07)

0

.002(1.10)

.001(1.73)

-.95(.13)

.45(.12)

.95(.17)

.46(.20)

.15(.05)

.07(.04)

1.36(.33)

.75(.23)

1.29(.20)

.43(.59)

2.10(.23)

1.10(.23)

-.18(.08)

.08(.08)

.47(.17)

.20(.08)

.013(.005)

.011(.004)

.147(.077)

.100(1.15)

.170(.037)

.095(.144)

.69(.14)

.20(.09)

.88(.25)

.56(.17)

.13(.08)

.17(.06)

-.08(.09)

-.25(.1 )

.14(.05)

.15(.07)

.08(.06)

.07(.05)

.16(.06)

-.23(. 11)

-.22(.10)

-.13(.07)

-.20(.1 1)

-.18(.()8)

.13(.()05)

.10(.09)

.23(.13)

.63(.13)

.44(.10)

.16(.10)

.13(.08)

.14(.10)

.42(.18)

.19(.08)

.22(.1 1)

.74(.31)

.16(.06)

.27(. 1 )

aToothpastebrandsare I, 2, 3, and 4, and toothbrushbrandsare 1, 2, 5, and 6.

hNo-purchaseoption constantis set to zero for identificationpurposes.

Notes: Figuresin boldface indicateparameterestimates associatedwith the cross-effectsof marketing-mixvariablesand the cross-categoryparamleters

that

govern the process of updatingthe utility errorterm varianceover time.

416

JOURNAL OF MARKETINGRESEARCH, NOVEMBER 2002

confirms the finding in the literaturethat use experience

may reduce uncertainty across categories for umbrella

brands (Erdem 1998) and establishes the new result that

advertisingdecreases consumer uncertaintyacross product

categories for umbrellabrandsas well.

Note also thatthe precisionof use experienceinformation

is found to be higher than that of advertisingin both categories, which is an intuitive result because use experience

should provide less noisy informationthan advertisingdoes

in most cases. Also, the ratioof advertisingvariabilityto use

experience variability is higher for toothpaste than toothbrushes; that is, although advertisingprovides more noisy

informationthandoes use experiencein both categories,the

relative noisiness of advertising informationis greater for

toothpastethan toothbrushes.

Finally, we estimated several within-categoryas well as

across-category correlations, as discussed in the previous

section. Not all the correlationsbetweenbrandconstantsand

price (advertising) responses are statistically significant.

The statistically significant estimates suggest that in the

toothpaste(toothbrush)category,consumerswho like Brand

I (Brand2) more than the averageconsumertend to be less

price sensitive than the average consumer.The reverse is

true for Brand 4. Therefore,the correlationbetween brand

specific constants and price sensitivity is positive for some

brandsand negative for others. The estimates also suggest

thatconsumerswho like Brands 1, 2, and 3 in toothpasteand

Brands 1 and 2 in toothbrushesmore than the averageconsumertend to be more advertisingsensitivethanthe average

consumer. Finally, in both categories, there are statistically

significantcorrelationsof price sensitivity with advertising,

display, feature, and use experience sensitivities. Advertising and featuresensitivities and advertisingand display sensitivities are significantly correlated in both categories as

well. Advertising and coupon availability sensitivities, as

well as advertisingand use experiencesensitivities, are significantlycorrelatedonly in the toothpastecategory.

Given the signs of the parameterestimates, these combined results indicate that in the two categories we study,

there seems to be an individual-specific trait we call

"marketing-mixsensitivity" (i.e., some consumers are in

general more sensitive to marketing-mixstrategies).Indeed,

similar results have been found in otherrecent work as well

(Arora2000). The only result that seems somewhatsurprising is the negative sign of the correlationbetween use experience and price sensitivities. Although these correlation

terms do not necessarily imply any causal links, we might

still have expected the reverseresultto hold. This is because

high use experience involves positive purchase feedback,

and consumers who are sensitive to this may be expected to

be less price sensitive (Seetharaman,Ainslie, and Chintagunta 1999). However, note that the estimate we obtain is

not necessarily counterintuitive.This is because more use

experience-sensitive people may have utility fartherout in

the tail of the distributionand may need a largerprice coefficient to have the same price elasticity.This would be consistent with high sensitivity to use experience being associated with high price sensitivity.Anotherexplanationfor the

result is that consumers with higher sensitivity to use experience may have smaller considerationsets (Rajendranand

Tellis 1994); this may increasethe abilityof use experiencesensitive consumers to make price comparisons,which may

result in higher price sensitivities in these two categories,

ceteris paribus.Finally, we also find that consumer price,

advertising,and use experience sensitivities are correlated

across the two categories we study.

Policy Simulations

To evaluatethe impactof temporarypolicy changes (i.e.,

a change in one of the marketing-mixelements in the second

week) in each category, we ran the following simulations

separatelyfor Brand I and Brand2: a 20% increase in (1)

coupon availability,(2) advertising,(3) displays, and(4) features and (5) a 20% decrease in price. We reportonly the

impact of the policy change on the cumulative purchases.

The impactof the temporarychangeon cumulativesales can

be conceptualizedas the long-termeffect of these temporary

policy changes. In regardto the short-termeffects of a temporarypolicy change (i.e., the impactof a policy change in

the beginningof the second week on sales in that week), it

may suffice to indicatethat the short-termeffects are larger.

It is also worthwhile to note that we found the long-term

effects to be largerthanthe short-termeffects in advertising.

Table 4 reports the results for the respective temporary

policy changes adoptedby Brand I in toothpasteand toothbrushesseparately.Table5 reportsthe correspondingresults

for Brand2. In bothTables4 and 5, the first half of the table

compares the baseline figures with the cumulative "sales"

figures when a temporarypolicy change was adopted in

Week 2 (orjust beforeWeek 2 in the case of advertisingand

coupon availability).In particular,the first row indicatesthe

baseline figures.The next five rows indicate the impacts of

a change in pricing, couponing, advertising, display, and

featurepolicy, respectively,in toothbrushon toothpasteand

toothbrushsales. The following five rows revealthe impacts

of a change in pricing, couponing, advertising,display, and

featurepolicy, respectively,in toothpasteon toothpasteand

toothbrushsales. The lower half of the table reportsthe percentage change in sales due to the respectivepolicy changes,

again separatelyfor toothbrushesand toothpaste.The tables

do not include the featureeffects in toothpaste,because the

cross-effects of features were found to be statistically

insignificantfor toothpaste.

To assess the impact of a 20% increase in Brand I's

advertising frequency in toothbrushes on the toothpaste

sales of Brand I, for example, comparethe baseline figure

of 1326, which reflects the baseline cumulative sales of

Brand I, with the correspondingpostintervention(a temporary increasein advertisingfrequencyby Brand I in toothbrushes at PurchaseOccasion 2) figure of 1431. This comparison reveals an 8% increase in toothpastesales due to a

20% increase of advertising frequency of Brand I in the

toothbrushcategory.

The resultson spillovereffects (cross-effects)can be summarized as follows: Overall, coupons and then advertising

have the largest cross-effects on sales in both categories

except for Brand2 in the toothpastecategory,for which features (more so than any other marketing-mixelement in the

toothpastecategory)affect sales the most in the toothbrush

category, followed by coupons and advertising. In most

cases, the smallest cross-effects are the price cross-effects.

The cross-effectsof coupon availabilityon sales rangefrom

5% to 13%acrossproductcategoriesand across Brand I and

Brand2. The ~

cross-effects

advertising

~ ~

~ ~ rangefi-om40%to 8%.

?

I

417

Advertising and Sales Promotions in Umbrella Branding

Table 4

SIMULATION

RESULTSFOR POLICYCHANGESBY BRAND1

Sales of Toothbrush

Sales of Toothpaste

Brand I

Brand2

Brand 3

Brand4

Brand I

Brand 2

Brand5

Brand6

Baseline

1326

777

424

353

99

256

160

106

Toothbrush

Price cut by 20%

Coupon increaseby 20%

Advertisingincrease by 20%

Display increase by 20%

Featureincrease by 20%

1405

1464

1431

1419

734

713

734

730

402

384

388

397

339

319

327

334

121

118

125

124

116

245

245

141

243

246

154

155

153

152

155

101

103

102

102

104

Toothpaste

Pricecut by 20%

Coupon increaseby 20%

Advertisingincrease by 20%

Display increase by 20%

Featureincrease by 20%

1748

1763

1665

1659

1641

519

571

594

600

604

334

299

338

340

343

279

255

283

281

292

105

112

107

105

104

252

248

252

253

255

159

158

157

159

158

105

103

105

104

104

Toothbrush

Toothpaste

BrtandI

Brand2

Brand3

B-rand4

Brand I

Brand2

B-rand5

B-rand6

Toothbrush

Price cut by 20%

Coupon increase by 20%

Advertisingincrease by 20%

Display increase by 20%

Featureincrease by 20%

.0596

.1041

.0792

.0701

-.055

-.082

-.055

-.06

-.052

-.094

-.085

-.064

-.04

-.096

-.074

-.054

.2222

.19/9

.2626

.2525

.17/7

-.043

-.043

-.449

-.051

-.039

-.038

-.031

-.044

-.05

-.031

-.047

-.028

-.038

-.038

-.019

Toothpaste

Price cut by 20%

Coupon increaseby 20%

Advertisingincrease by 20%

Display increase by 20%

Featureincrease by 20%

.3183

.3296

.2557

.2511

.2376

-.332

-.265

-.236

-.228

-.223

-.212

-.295

-.203

-.198

-.191

-.21

-.278

-.198

-.204

-.173

.0606

.1313

.0808

.0606

.0505

-.016

-.031

-.016

-.012

-.004

-.006

-.013

-.019

-.006

-.013

-.009

-.028

-.009

-.019

-.019

Notes: The cross-effects are indicatedin bold and the own-effects are indicatedin italics. The figures in bold and italics refer to the impactsof the policy

changes on the sales of the umbrellabrandimplementingthe policy change.

The display cross-effects range from 3% to 7%. Similarly,

the feature cross-effects in toothbrush (the impact of a

change in the display activity in toothpasteon toothbrush

sales) are 5% for both Brands I and 2. Finally,price crosseffects range from 3% to 6% as well in both categories.

The simulation results for a temporarypolicy change by

Brand I (Brand2) in the toothbrushcategorysuggest thatas

a percentageof the own-effects, cross-effects on Brand I's

(Brand 2's) toothpaste sales are 27%, 54%, 30%, and 28%

(23%, 61%, 43%, and 64%) for price, coupon availability,

advertising, and display, respectively. Thus, in the toothpastector

couponavailabilityandthen advertisinghave

category,

the largest cross-effects as a percentageof own-effects for

Brand I, and displays and coupons have the largest crosseffects as a percentageof own-effects for Brand2. The simulation results for a temporarypolicy change by Brand I

(Brand 2) in the toothpastecategory suggest that as a percentage of the own-effects, cross-effects on Brand I's

(Brand2's) toothbrushsales are 19%,40%, 32%, 24%, and

21% (16%, 61%, 43%, 64%, and 29%) for price, coupon

availability, advertising, display, and feature, respectively.

Thus, in the toothbrushcategory, as in the toothpastecategory, cross-effects as a percentageof own-effects are largest

for coupons and advertisingfor Brand 1. For Brand2, in the

toothbrushcategory, cross-effects as a percentageof owneffects are largestfor features,because of a policy change in

the toothpastecategory, followed by coupons and advertis-

ing. In contrast,in the toothpastecategory these effects are

largestfor display and coupons, followed by advertising.As

these numbersshow, as a percentageof own-effects, crosseffects are substantialfor all marketing-mixelements.

MANAGERIAL

IMPLICATIONS,

CONCLUSIONS,AND

FURTHERRESEARCH

We tested for the spillovereffects of advertisingand other

marketing-mix/salespromotion strategies (price, coupon,

display,and feature)in umbrellabrandingon scannerpanel

data.We found that advertisingspillover effects, along with

the use experiencespillovereffects, affect both utility mean

and variance. The latter effect provides evidence for the

uncertainty-reducingrole of advertising (along with use

experience) across categories for umbrellabrands.To capture the varianceeffect in a parsimoniousway, for the first

time in the literature,we estimated a multivariatemultinomialprobitmodel, in which the variancesandcovariances

of random components of utilities across categories were

updatedon the basis of use experience and advertising.

Although there were some differences across categories

and brands,marketing-mixspillover effects were largestfor

coupon availability,generally followed by advertising.The

relativelylargecoupon effects, as well as advertisingeffects,

can be explained by various behavioralphenomenarelated

to brandequity; for example,couponingor advertisingby an

umbrellabrandmay increaseconsumer awarenessof prod-

JOURNAL OF MARKETINGRESEARCH, NOVEMBER 2002

418

Table 5

SIMULATION

RESULTSFORPOLICYCHANGESBY BRAND2

Sales of Toothbrush

Sales of Toothpaste

Brand I

Brand2

Brand3

Brand4

Brand I

Brand2

Brand5

Brand6

Baseline

1326

177

424

353

99

256

160

106

Toothbrush

Price cut by 20%

Coupon increaseby 20%

Advertisingincrease by 20%

Display increaseby 20%

Featureincreaseby 20%

1294

1270

1306

1311

813

867

829

814

419

403

404

410

354

340

341

345

85

84

85

95

96

307

305

296

275

271

140

142

146

152

153

89

90

94

99

101

Toothpaste

Price cut by 20%

Coupon increaseby 20%

Advertisingincrease by 20%

Display increase by 20%

Featureincreaseby 20%

1206

1207

1226

1237

1246

966

963

950

924

915

382

383

385

392

390

326

327

319

327

329

95

94

94

95

93

266

269

267

264

269

157

156

158

158

157

103

102

102

104

102

Br-andI

Brand2

Brand3

Brand4

Brand I

Brand2

Brand5

Brand6

Toothbrush

Price cut by 20%

Coupon increaseby 20%

Advertisingincrease by 20%

Display increase by 20%

Featureincrease by 20%

-.024

-.042

-.015

-.011

.0463

.1158

.0669

.0476

-.012

-.05

-.047

-.033

.0028

-.037

-.034

-.023

-.141

-.152

-.141

-.04

-.03

. 992

.1914

.1563

.0742

.0586

-.125

-.113

-.088

-.05

-.044

-.16

-.151

-.113

-.066

-.047

Toothpaste

Price cut by 20%

Coupon increaseby 20%

Advertisingincrease by 20%

Display increase by 20%

Featureincrease by 20%

-.09

-.09

-.075

-.067

-.06

.2432

.2394

.2227

.1892

.1776

-.099

-.097

-.092

-.075

-.08

-.076

-.074

-.096

-.074

-.068

-.04

-.051

-.051

-.04

-.061

.0391

.0508

.043

.0313

.0508

-.019

-.025

-.013

-.013

-.019

-.028

-.038

-.038

-.019

-.038

Toothbrush

Toothpaste

Notes: The cross-effects are indicatedin bold and the own-effects are indicatedin italics. The figures in bold and italics refer to the impactsof the policy

changes on the sales of the umbrellabrandimplementingthe policy change.

ucts that share the same umbrellabrand(Aaker 1991) and

may strengthenthe brandimage (Keller 1993). Given that

clipping the coupons and using them requiresmore cognitive elaborationon the partof consumers,such cross-effects

may even be largerfor coupons than for advertising,as our

results indicate.

We also found thatadvertising(as well as use experience)

shifts both utility mean and variance across categories.

Thus, we found that the varianceof the randomcomponent

of utility in each categorydeclined as a resultof advertising

(and use experience) in eithercategoryover time. The crosscategory effects of advertisingon the utility mean may be

due to the factors discussed previously,such as awareness,

as well as advertising'seffect of increasingquality beliefs

underuncertainty.However,the effect of advertisingon utility varianceis evidence for learningdue to advertisingunder

uncertainty (the variance of quality beliefs is decreasing

over time because of advertising).Thus, we find evidence

for the uncertainty-reducingrole of advertisingacross categories, which gives rise to advertising spillover effects,

though the effects on mean utility may be a combinationof

different impacts (relatedor not relatedto uncertainty).

Our empirical results obtained from the analysis of

revealed preference data have several other managerial

implications. First, the results confirm the expectation that

umbrella brandinggenerates savings in branddevelopment

and marketingcosts over time and enhances marketingpro-

ductivity.These results call for integratedmarketingcommunications across products that share the same brand

name. Work on brandequity suggests this for advertising,

butour resultssuggest thatthe need for integrationexists for

all the marketing-mixelements, includingsales promotions

and especially couponing strategies, given the relatively

large cross-couponingeffects we found.

Second, our results imply that there are some asymmetries across productcategoriesand across brands.Forexample, for Brand 2, featuringtoothpastewill have the largest

cross-effects on toothbrushsales, whereas displaying the

toothbrushproduct(or giving a coupon for it) will have the

largestcross-effectson toothpastesales, ceteris paribus.Furthermore,as a percentageof own-effects, cross-effects of a

policy change in toothbrushseem to affect toothpastesales

more than the other way around in the case of Brand 2,

whereas the magnitudesof cross-effects as a percentageof

own-effects are fairly similar across the two categories for

Brand 1. Therefore,it would be importantfor brandmanagers to know how specific cross-effects work across categories for their brands.

Although it was not the focus of this article,we also estimated and found evidence for several within- and crosscategory correlations in response coefficients. First, we

Iound that marketing-mixsensitivities are generally positively correlated within a category. We also found that

depending on the brandin question, some consumers who

419

Advertising and Sales Promotions in Umbrella Branding

like certain brands may be more or less price sensitive than

the average consumer. These results indicate that in these

two categories, there are segments that, overall, are

marketing-mix sensitive, as well as segments that are

marketing-mix insensitive. Second, the finding that consumers' marketing-mix sensitivities tend to be correlated

across categories suggests that there is a strong individualspecific component to marketing-mix sensitivity.

There are a few avenues for further research. We showed

evidence for both utility mean- and utility variance-shifting

effects of advertising and use experience, and the the variance effects indicate evidence for the uncertainty-reducing

role that advertising and use experience play across categories for umbrella brands. The processes by which these

spillover effects occur are worth exploring in more detail.

However, as discussed by Keane (1997a), because of identification issues that arise with respect to models estimated on

panel data, it is often not feasible to differentiate among all

possible behavioral processes using scanner panel data. Survey or experimental data would be needed to provide a

detailed account of all the underlying behavioral processes.

REFERENCES

Aaker, David A. (1991), Managing Brand Equity.New York:The

Free Press.

and Kevin L. Keller (1990), "ConsumerEvaluationsof

BrandExtensions,"Journalof Marketing,54 (January),27-41.

Abe, Makoto (1997), "A Household-LevelTelevision Advertising

Exposure Model,"Journal of MarketingResearch,34 (August),

394-405.

Ainslie, Andrewand PeterE. Rossi (1998), "Similaritiesin Choice

Behavior Across Product Categories,"MarketingScience, 17

(2), 91-106.

Allenby,Greg M. and James M. Ginter(1995), "UsingExtremesto

Product Design Products and Segment Markets,"Journal of

MarketingResearch, 32 (4), 392-403.

Arora,Neeraj(2000), "UnderstandingLoss Aversionand the Role

of Multiple Reference Points:A HierarchicalBayes Approach,"

workingpaper,MarketingDepartment,Universityof Wisconsin.

Bell, David and James Lattin (1998), "Shopping Behavior and

ConsumerPreferencefor Store Price Format:Why 'Large Basket' ShoppersPrefer EDLP,"MarketingScience, 17 (1), 66-88.

Erdem,Tulin (1998), "An EmpiricalAnalysis of UmbrellaBranding,"Journal of MarketingResearch,34 (August), 339-51.

and Michael P. Keane (1996), "Decision-MakingUnder

Uncertainty: Capturing Choice Dynamics in TurbulentConsumerGoods Markets,"MarketingScience, 15 (1), 1-20.

and Russell Winer (1999), "Econometric Modeling of

Competition: A Multi-category Choice-Based Mapping

Approach,"Journal of Econometrics,89, 159-75.

Geweke, John (1991), "Efticient Simulation from Multivariate

Normal and Student-t distributions Subject to Linear Constraints,"in ComputerScience and Statistics Proceedingsof the

Twenty-ThirdSymposiumon the Interface,E.M. Keramidas,ed.

Alexandria,VA: AmericanStatisticalAssociation, 571-78.

Guadagni,Peter M. and John D.C. Little (1983), "A Logit Model

of BrandChoice Calibratedon Scanner Data,"MarketingScience, 2 (Summer), 203-38.

Hajivassiliou, Vassilis, Dan McFadden, and Paul Ruud (1994),

"Simulation of Multivariate Normal Orthant Probabilities:

Methods and Programs,"WorkingPaperSeries DP 31021. New

Haven,CT: Yale University,Cowles Foundation.

Heckman, James B. (1981), "Heterogeneityand State Dependence," in Studies in Labor Markets, S. Rosen, ed. Chicago:

Universityof Chicago Press, 91-139.

Ho, Teck, ChristopherS. Tang, and David Bell (1998), "Rational

Shopping Behavior and the Option Value of VariablePricing,"

ManagementScience, 44 (2), 145-60.

Keane, Michael P. (1990), "FourEssays in EmpiricalMacro and

Labor Economics," doctoral dissertation,Departmentof Economics, Brown University.

(1994), "Simulation Estimation for Panel Data Models

with Limited DependentVariables,"in Handbookof Statistics,

G.S. Maddala,C.R. Rao, and H.D. Vinod, eds. New York:Elsevier Science Publishers,545-71.

(1997a) "CurrentIssues in Discrete Choice Modeling,"

MarketingLetters,8 (3), 307-22.

(1997b), "Modeling Heterogeneityand State Dependence

in ConsumerChoice Behavior,"Journal of Business and EconomnicStatistics, 15 (3), 310-27.

Keller, Kevin L. (1993), "Conceptualizing,Measuring,and Managing Consumer-BasedBrandEquity,"Journalof Marketing,57

(1), 1-22.

Lane, Vicki R. and RobertJacobson(1995), "Stock MarketReactions to BrandExtensionAnnouncements:The Effects of Brand

Attitudeand Familiarity,"Journalof Marketing,50 (1), 63-77.

Leigh, James H. (1984), "Recalland RecognitionPerformancefor

UmbrellaPrintAdvertisements,"Journalof Advertising,13 (4),

5-18.

Loken, Barbara and Deborah Roedder John (1993), "Diluting

Brand Equity: When Do Brand Extensions Have a Negative

Impact?"Journalof Marketing,57 (July), 71-84.

Manchanda,Puneet, Asim Ansari, and Sunil Gupta (1999), "The

'Shopping Basket': A Model for MulticategoryPurchaseIncidence Decisions,"MarketingScience, 18 (2), 95-114.

,and

(2000), "Multi-categoryBranding

Effects: A Shopping Trip Based Analysis," paper presentedat

the 2000 MarketingScience Conference, Universityof California, Los Angeles (June).

McFadden,Daniel (1974), "ConditionalLogit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behavior,"in Frontiersof Economletrics,P. Zarembka, ed. New York:Academic Press, 105-42.

(1989), "A Methodof SimulatedMomentsfor Estimations

of Discrete Response Models Without Numerical Integration,"

Econometrica,57 (5), 995-1026.

Montgomery, Cynthia A. and Birger Wernerfelt(1992), "Risk

Reductionand UmbrellaBranding,"Journalof Business, 65 (1),

31-50.

MulhernJ. Francis and Robert P. Leone (1991), "ImplicitPrice

Bundlingof Retail Products:A MultiproductApproachto MaxJournalof Marketing,55 (October),

imizing Store Profitability,"

63-76.

Rajendran,K.N. andGerardJ. Tellis (1994), "ContextualandTemporalComponentsof ReferencePrice,"Journalof Marketing,58

(January),22-34.

Rangaswamy,Arvind, Raymond Burke, and Terence A. Oliver

(1993), "BrandEquity and the Extendibilityof BrandNames,"

International Journal of Research in Marketing, 10 (March),

61-75.

Roberts,John and PrakeshNedungadi(1995), "StudyingConsideration in Consumer Decision Process: Progress and Challenges," International Jour-lnalof Research in Marketing, 12 (1),

3-7.

and Glenn Urban(1988), "ModelingMultiattributeUtility,

Risk and Belief Dynamics for New Consumer Durable Brand

Choice," Managemenllt Science, 34 (2), 167-85.

JOURNAL OF MARKETINGRESEARCH, NOVEMBER2002

420

Rossi, Peter E. and Greg M. Allenby (1993), "A Bayesian

Approach to Estimating Household Parameters,"Journal of

MarketingResearch,30 (2), 171-82.

, Robert E. McCulloch,and Greg M. Allenby (1996), "On

the Valueof HouseholdInformationin TargetMarketing,"Marketing Science, 15 (4), 321-40.

Russell, Gary,S. Ratneshwar,andAllan D. Shocker(1999), "Multiple Category Decision-Making:Review and Synthesis,"Marketing Letters, 10 (3), 301-18.

Seetharaman,P.B., Andrew Ainslie, and Pradeep K. Chintagunta

(1999), "Investigating Household State Dependence Effects

Across Categories," Journal of Marketing Research, 36

(November),488-500.

Tauber,E.M. (1981), "BrandFranchiseExtension: New Product

Benefits from Existing Brand Names," Business Horizons, 24

(March/April),36-41.

(1988), "BrandLeverage:Strategyfor Growthin a CostControlled World," Journal of Advertising Research, 28

(August/September),26-30.

Tellis, GerardJ. and Doyle L. Weiss (1995), "Does TV Advertising

Really Affect Sales?"Journalof Advertising,24 (3), 1-12.

Wernerfelt,Birger(1988), "UmbrellaBrandingas a Signal of New

ProductQuality:An Exampleof Signaling by Posting a Bond,"

RANDJournalof Economics, 19 (3), 458-466.

FOR

PAPERS

CALL

APPLIED PROBABILITYMODELS AND MEASUREMENT

IN MARKETING

Due to an increasedavailabilityof dataandalso to an increasedinterestamongstthe practitioners,

one can notice more and more applicationsof statisticaltechniquesand stochasticmodels in

marketing.It is not uncommon that marketingdecisions are made based on the outcomes of

sophisticatedmodels for empiricaldata.As developmentsin this areaproceedwith rapidpace, it

is importantto once in a while establishthe currentstate of the art concerningthese empirical

models. It is for this reason that the journalAppliedStochastic

Modelsin Businessand Industry

is

a

issue

on

(Wiley) publishing special

Applied Probability Models and Measurement in Marketing.

All empiricalworkrelatedto the probabilisticmodellingof choice,preference,and/orbehaviouris

welcome.Analysisof largedatasets is also encouraged.Paperscan be submittedelectronicallyto

the Guest Editors:

AlbertBemmaor

ESSEC

BP 105

95021 Cergy Pontoise Cedex

France

bemmaor@essec.fr

or

PhilipHansFranses

ErasmusUniversity

P.O.Box1738

NL-3000DR Rotterdam

The Netherlands

franses@few.eur.nl

The deadlinefor submissionis June 30, 2003. All paperswill be refereed,and there is no a priori

guarantee of ultimate acceptance.