Mass psychology of disasters and emergency evacuations

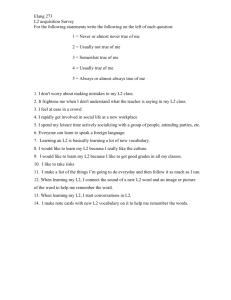

advertisement