Bystander Intervention during the 7/7 London bombings: an account

advertisement

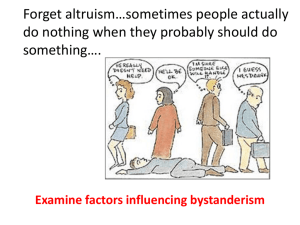

Bystander Intervention during the 7/7 London bombings: an account of survivor's experiences Chris Cocking, John Drury, & Steve Reicher Outline Context of Bystander Effect Social Identity approaches July 7th 2005 and bystander intervention Wider implications/ future developments? Individual good- group bad? Crowds initially seen as influencing over-reaction and/or irrational behaviour (e.g. Le Bon, 1895) But Latané & Darley (1968) suggest that crowds can also encourage inhibition and inaction Shift from view of crowd as active threat to passive threat (Manning et al, in Press) So group action still seen as worse than individual behaviour Background to Bystander Effect Diffusion of responsibility can happen in emergencies with people delaying action with fatal results e.g. experimental and field studies Sime (1995) Time to escape= t¹ (time to start to move)+ t² (time to pass through exits) Latané & Darley (1968) suggest BE more likely, the bigger the crowd Garcia et al (2002) Implicit BE studiesdeindividuation within crowd Development of Bystander Effect More to BE than physical size of crowd Role of emotional connection with victims Helping/altruism more likely if empathy with victim (e.g Batson 1991) People more likely to help others they identify with, (e.g. Cialdini et al 1997; Dovidio et al 1997) Role of SCT- ‘it is not simply the presence or absence of others that affects intervention, but who those others are perceived to be’ (Levine & Thompson 2004) Context of research ESRC funded project investigating crowd behaviour in emergencies Applying SIT/SCT models of crowd behaviour Exhibiting our VR programme at Royal Society on 7/7 Decided to gather data from survivors 7/7 Data collected 90 survivors 56 eye-witnesses archive, questionnaire, e-mail, and interview data (12 interviewed in person-6 male, 6 female) www.sussex.ac.uk/affiliates/panic/lb/index.htm 7/7: chronology of events Bombs explode- brief silence in the darkness Screams of fear and distress- passengers try to find out what’s going on Smoke & soot clear- attempts to help/ comfort others, & escape- some delay because of fear that tracks are live Some passengers wait up to 45 mins for rescue, and walk in orderly fashion along tracks when directed Typical rush-hour on tube Normal rush-hour behaviour, diffusion of responsibility/bystander effect could be expected because; Atomised commuters on way to work Minimal common identity Individual injuries/casualties unlikely to threaten group as a whole Behaviour on 7/7 Helping & co-operation rather than selfish behaviour Individual selfish acts rare and don’t spread No evidence of mass panic Only minor evidence for BE, despite minimal existing emotional/affiliative ties amongst participants Why no bystander effect on 7/7? Clear, shared threat to group survival Common identity emerges in response to this shared threat This emergent unity encourages helping and intervention rather than apathy Being in psychological crowd appears to make helping more, not less likely Bystander intervention on 7/7 Examples of co-operation LB7: these guys helped me up on the platform and then this woman came and asked if I was alright and then held my hand as we walked up the platform together. And um got the lift up to the tube station and sat down for ages and ages and then this really nice woman came and sat with me and put her coat round me kind of looked after me Female, early 20s, King’s Cross (in carriage bombed) Common identity CC: Can you remember when this strong sense of unity first emerged? LB7: I guess probably straight away and then it probably grew a bit but as soon as it happened and people were screaming there was another guy saying calm down and people were talking to each other straight away and obviously something huge had happened and we just kind of instantly felt quite together really. Physical-psychological crowd LB1: on a normal day on the tube you’re fighting for your own seat, fighting for a decent spot to hold onto, and you don’t you don’t let people through and fight to get on and off the train at first. I think the whole atmosphere changed completely, it was refreshing to see that the human beings that we are, were able to change their behaviour to the situation in hand and normal behaviour on the train at that time of the morning is fight, once you get your seat you put your head in the Metro newspaper and that’s it until you get off but people actually interacted with each other and helped each other and were being considerate Male, late 20s. Edgware Rd (witnessed blast) Some minor diffusion of responsibility LB1: there was one guy that was on the train very shortly after the blast happened I don’t know how he got a signal cos we were still in the tunnel but he rang up work to cancel his meetings, and this lady stood next to him said don’t you think you should dial 999 to get the emergency services round and he said somebody else would have done that so there’s no point me doing that’s about the only selfish act I think, I don’t know if it was truly selfish as he was just standing there with nothing else to do so he thought he would phone his office Lasting effects? LB12: I’ve noticed that more maybe since, just the other day somebody passed out half way on and off the tube and I pulled the emergency cord which I did that day, and I was thinking oh I am making a habit of this now. You know and there was about 4 or 5 people and we managed to get her back on the platform, one of the guys was actually a doctor who had a look at her and she had just passed out [] I mean contrary to what everyone says about we all ignore each other. We do we you know it’s early in the morning or late at night you’re tired you’re knackered you just want to sit there and read your paper or whatever but if something happens generally I would say that most people on the tube would help Female 50s Aldgate (on train bombed) Enduring common identity Common identity clearly very powerful in short-term, and can overcome BE, but does it endure? Unclear, but some evidence that it does and may also provide mutual support or shield from stress/ trauma (e.g. KCU) However possibility of maladaptive nature of such groups Area we want to explore in more detail Mutual support groups post 7/7 Summary Less evidence for bystander effect in mass emergencies Intervention does not necessarily decrease as group size increases Shared fate can create psychological unity which encourages intervention/ co-operation Is such unity enduring and/ or helpful in other areas? References Batson (1991) The Altruism Question Cialdini et al (1997) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Dovidio et al (1997) Journal of Experimental Social Psychology Garcia et al (2002) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Le Bon (1895) The Crowd Latané & Darley (1968) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Levine & Thompson (2004) Journal of Social Psychology Manning et al (in Press) American Psychologist Sime (1995) Safety Science