and WorkChoices - University of South Australia

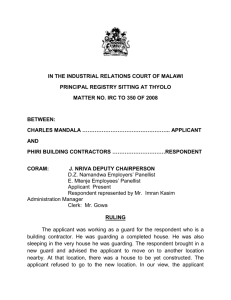

advertisement