Slide 2: Benefits of urbanization Cities themselves are inherently

advertisement

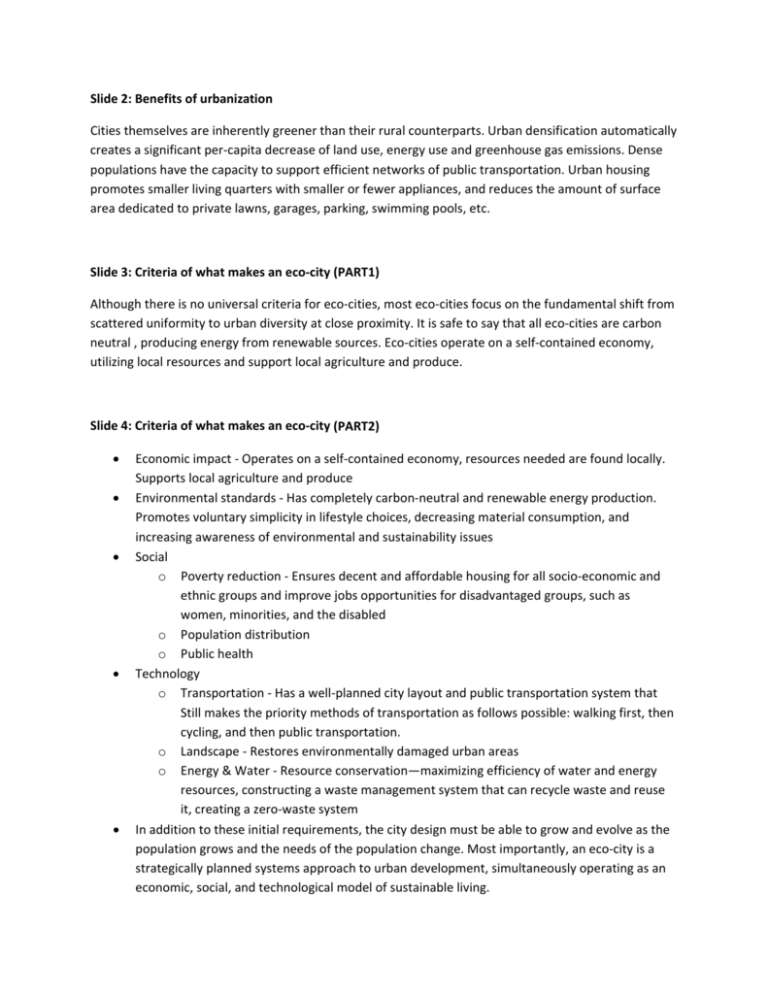

Slide 2: Benefits of urbanization Cities themselves are inherently greener than their rural counterparts. Urban densification automatically creates a significant per‐capita decrease of land use, energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. Dense populations have the capacity to support efficient networks of public transportation. Urban housing promotes smaller living quarters with smaller or fewer appliances, and reduces the amount of surface area dedicated to private lawns, garages, parking, swimming pools, etc. Slide 3: Criteria of what makes an eco‐city (PART1) Although there is no universal criteria for eco‐cities, most eco‐cities focus on the fundamental shift from scattered uniformity to urban diversity at close proximity. It is safe to say that all eco‐cities are carbon neutral , producing energy from renewable sources. Eco‐cities operate on a self‐contained economy, utilizing local resources and support local agriculture and produce. Slide 4: Criteria of what makes an eco‐city (PART2) Economic impact ‐ Operates on a self‐contained economy, resources needed are found locally. Supports local agriculture and produce Environmental standards ‐ Has completely carbon‐neutral and renewable energy production. Promotes voluntary simplicity in lifestyle choices, decreasing material consumption, and increasing awareness of environmental and sustainability issues Social o Poverty reduction ‐ Ensures decent and affordable housing for all socio‐economic and ethnic groups and improve jobs opportunities for disadvantaged groups, such as women, minorities, and the disabled o Population distribution o Public health Technology o Transportation ‐ Has a well‐planned city layout and public transportation system that Still makes the priority methods of transportation as follows possible: walking first, then cycling, and then public transportation. o Landscape ‐ Restores environmentally damaged urban areas o Energy & Water ‐ Resource conservation—maximizing efficiency of water and energy resources, constructing a waste management system that can recycle waste and reuse it, creating a zero‐waste system In addition to these initial requirements, the city design must be able to grow and evolve as the population grows and the needs of the population change. Most importantly, an eco‐city is a strategically planned systems approach to urban development, simultaneously operating as an economic, social, and technological model of sustainable living. Slide 5: Tianjin, China‐ (PART 1) Tianjin is a major city in Northern China. It is the fourth largest city in China. It is a major political and economic centre. As a key port city, Tianjin has a rapidly growing manufacturing and trade industry. Slide 6: Tianjin cont. Tianjin, with an expected population of 350,00, is located just 10 minutes from the business parks at the Tianjin Economic Development Area. It's advanced light rail system means that public transit will account for 90% of the city's commuting. 40% of the municipality is farmland. The city begins with a sustainable city model that is based on the key tenets of people‐people, people‐ environment and people‐economy harmony. Slide 7: Freiburg, Germany Unlike the modern start‐from‐scratch approach of Tianjin, Freiburg's sustainable policies were established in the 1970's. It was an initiative formed by citizens in opposition to nuclear power, who established a network of environmentalists, research organizations, and businesses dedicated to sustainable energy. It is considered the world's solar capital. Freiburg has actively committed to its three pillars for sustainable development: energy saving, new technology, and renewable energy sources. The city utilizes its natural location and its ability to attract renewable energy industries and research institutions to establish itself as a strong economic centre for sustainable living. Freiburg has also led improvements in transportation with over 500km of bicycle paths, efficient public transportation, and numerous car‐free zones. Waste management is promoted through recycling initiatives, subsidies and discounts for collective waste disposal and composting, and through using non‐ recyclable waste as bio‐fuel. Slide 10: Curitiba, Brazil ‐ (PART 1) Curitiba is a medium‐sized city in Brazil. It's also had some historical/political relevance to Brazil as it was once the capital of the country, albeit for only three days. It has had an incredible urban master plan since 1978; is currently considered one of the best examples for sustainable urban growth. Slide 11: Case Study 3 ‐ (PART 2) Part of this master plan includes: 1. Urban growth is restricted to corridors of growth ‐ along key transport routes. Tall buildings are allowed only along bus routes. 2. Creating and retaining parks and green space beside the rivers to act as floodplains. When the Iguazu River floods, some areas created are used as boating lakes. Slide 12: Case Study 3 ‐ (PART 3) Other points included in the master plan are: 1A green exchange programme. The urban poor bring their waste to neighbourhood centres. They can exchange their waste for bus tickets and food. This has many advantages, for example the urban poor areas are kept clean, despite waste trucks not being able to reach them easily. Slide 13: Moreland, Australia ‐ (PART 1) Has been working on becoming a sustainable/eco‐city for ten years in conjunction with the city of Melbourne. The Moreland Energy Foundation is a local organization that provides services to the community to upgrade buildings and infrastructure. They also act as a lobby group. Slide 14: Case Study 4 ‐ (PART 2) The MEF works along seven paths to help Moreland reach eco‐city status: 1. Community action: influence community, encourage participation 2. Energy efficiency: work to help local citizens improve their homes and business' energy efficiency and reduce carbon footprint. Slide 15: Case Study 4 ‐ (PART 3) 1. Energy supply: monitor energy consumption, research alternative energy technology 2. Urban development: planning proposals for increased density and redevelopment Slide 16: Problems adopting Eco‐City mandate (PART 1) Essentially, how do cities bridge the costs of having to maintain and upgrade existing infrastructure while also developing new infrastructure as well? There is no easy answer as these projects don't help in maintaining municipal or national debt at a stable level. Slide 17: Problems adopting Eco‐City mandate (PART 2) How can we make the idea of eco‐cities marketable? Should they be marketable ‐ is the exploitation of ideals inevitable? If we provide incentives for corporations to buy into the eco‐city model... would we corrupt the idea of the eco‐city or facilitate a turnabout in economic ideals? Slide 18: Problems adopting Eco‐City mandate (PART 3) How does poverty factor into all of this? Although cities like Curitiba have shown progress in helping to reduce poverty, to what level can an eco‐city reduce poverty or eradicate it entirely? How effective and sustainable are the policies that cities use to assist the impoverished? Slide 19: Problems adopting Eco‐City mandate (PART 4) What about agriculture? In incredibly dense urban areas such as eco‐cities, how do we effectively produce and distribute health, yet affordable food to the citizens. Aside from outlying areas, can we perhaps have food production within the city itself? Does focusing of local food limit the range of eco‐ cities to regions with rich agricultural land? Slide 20: Criticisms/Ending Eco‐cities are undoubtedly a positive move towards more sustainable urban living, but the approach towards them need to be both a critical and open‐minded approach.