Resident Participation: History Repeating Itself?

advertisement

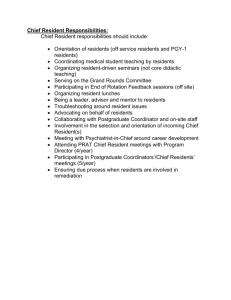

Resident Participation: History Repeating Itself? Colin Dilks Byker Village Residents Association, Byker Redevelopment, Newcastle upon Tyne, England In the United Kingdom significant amounts of regeneration funds are being targeted at inner city social housing estates in Northern England in order to address issues of low demand. It is often necessary for successful funding applications to require the involvement of local resident organisations in the bid process. However, the level and content of local resident participation and development in these projects can often be rather vague and misleading. This paper draws on the recent experience of living in a low demand, but architecturally significant, housing development in Newcastle upon Tyne, England. It compares residents’ experiences from a series of regeneration initiatives separated by a period of 40 years that have promoted resident participation. Emphasis will be on current government initiatives such as Local Strategic Partnerships and Housing Renewal Pathfinder and whether these integrate community development practices. Specific evidence will look at initiatives such as the introduction of Closed Circuit Television Camera coverage and an Urban Design Competition intending to rejuvenate the local housing market. The experience suggests that both the quantity and quality of resident participation and community development in these projects is not an empowering experience and that evidence is often misrepresented in official publicity. One government initiative to increase the level of participation by local people will be looked at. The paper concludes that sustainability in housing does not necessarily require large amounts of funding, teams of professionals, or resident ‘consultation’ but instead requires the opportunity for residents to empower themselves and develop structures that makes them active participants in the process and delivery of improved services. INTRODUCTION In 1999 the Joseph Rowntree Foundation published a report by Anne Power and Katharine Mumford (The slow death of great cities? Urban abandonment or urban renaissance) that outlined some of the issues facing cities in the North of England on a city, neighbourhood and localised level. The author of this paper explores the personal experience of a resident living in a large, low demand inner city social housing estate in Britain who has been involved in a series community ‘participation’ exercises since 1998. This involvement has included being on the management committee of the Byker Village Residents’ Association (one of four on the estate), the Steering Group of the Byker Area Resource Centre (the base for the Community Development Workers employed by the City Council), the Committee of the Byker Community Forum (a group of local representatives from residential, business, faith and service organisations), the Byker Listings Group (representatives from local organisations affected by the proposed heritage listing of the estate), the Byker Action Plan (representatives from local groups drawing together agencies delivering services on the estate) and most recently the Management Committee of the local City Farm and Chair of an Allotment Association. As both a resident and a community representative the author has experienced a series of regeneration initiatives that have invited ‘community participation’ in partnership with professionals from various organisations. Current national initiatives following on from the reports from the Urban Task Force in 1999 include Housing Market Renewal Pathfinder, Local Strategic Partnerships and the Community Empowerment Fund. On the whole the author has found the experiences to be negative ones. The initiatives are often misdirected and only seek to address the symptoms of the problems and not to find long term solutions. In addition, there is often significant damage caused to the community networks and infrastructure where selected groups are allowed to participate in initiatives and others are excluded. It is most often the case that ‘professionals’ living outside of the estate are employed in a paid capacity to provide services but that residents are engaged in a voluntary capacity, often in addition to full time employment or other responsibilities such as childcare, and with little support or development opportunities. RESEARCH METHODS: Desk-based study of documentation A range of different documents was studies as part of preparing the paper. These included: Minutes of the Byker Safety Group Minutes of the Byker Community Forum 1 Correspondence from Your Homes Newcastle Participant observation and discussions with residents and officers Unstructured interviews and observations were held with residents and officers in the area. These included: Community Development Workers Community Co-ordinator Community Representatives on the Byker Design Competition Local Residents Manager of the CCTV scheme Control room/Concierge staff Byker Housing Manager Socio-demographic data about the area This was obtained from the 2001 Census data. BACKGROUND The Byker Redevelopment The Byker neighbourhood is located 1mile east of the city centre of Newcastle upon Tyne, in north east th England. It originally developed in the 19 Century with the economic expansion of Tyneside during th the Industrial Revolution. By the mid 20 Century the Byker area was a working-class community of housing, churches, schools, public houses, local shops and public bath houses. The vast majority of housing was late 19th century terraced Tyneside flats (two storey brick buildings, one flat on the ground, one above) with a yard to the rear, outside toilets, coal fires and no gardens. As part of a wider modernisation plan across Newcastle in the 1950s Byker was scheduled as ‘unfit’ housing and large scale demolition was proposed. Inspection of clearance areas did not begin until 1959 and the first Compulsory Purchase Orders were not confirmed until 1963. Clearance began in the mid 1960s and did not end until 1979. Although Byker had retained its community spirit and it was this that influenced the council in its decision to redevelop with the intention of retaining the community, 13 years of uncertainty and demolition did take its toll on the stability of the community. In 1963 the Development Plan Review stated that ‘It has been necessary to consider what extent housing demands will change in the years ahead and to put forward a basis of a programme a standard for housing satisfaction which is very considerably higher than what exists today’1. Ralph Erskine (1914-2005) - a British born resident of Sweden since 1938 - was appointed as planning consultant in 1969 and his Plan of Intent prepared in 1970 envisioned a Nordic version of the English garden suburb. One of the main objectives was to ‘prepare a project for planning and building a complete and integrated environment for living in its widest sense, at the lowest possible cost to the residents, and in intimate contact and collaboration with them’2. It was envisioned that all of those who wished to be rehoused from the original Byker would be accommodated in the new estate and 80% of them wished to do so. The Perimeter Block consisting of 500 apartments (now known as the Byker Wall) is the exception to an otherwise low rise development and was designed as a barrier block to a proposed motorway to the north of the estate. Access decks to the apartments in the Wall have a conservatory at each lift entrance to encourage social interaction and balconies are scaled to encourage a sense of neighbourliness and security – each flat has a seat and flowerbox. The Redevelopment was designed as a mainly car-free environment, the majority of parking (1.25 spaces per dwelling) was provided on the outer edge of the estate with a series of pedestrian thoroughfares crossing the estate. ‘Byker, which was one of the last large scale local authority schemes to be built, has a special place in 3 British housing’ Most ground level houses were provided with gardens. The landscaping is designed to be integral to the plan of the estate. There are a series of interlinked public spaces to encourage social interaction and large amounts of soft landscaping were introduced to create hierarchy of privacy and to add interest. Erskine ‘suggested a co-management scheme so that tenants could become closely involved with council officials in running the area. They could be given money for projects like landscaping. Maintenance of the area would be important, if its appearance were not to revert to that of a run-down estate’4. 2 Many houses face south and are designed to catch the sun. Streets are built along contours to reduce the effect of steep gradients and to utilise the opportunity for panoramic views. Building materials are bright, varied and tactile with wide use of wood and metal. Garden fences are low. The human scale is emphasised. Essentially the estate is built for human interaction. One significant element of Erskine’s 14 year development was the opportunity for local residents to interact with the design team and to participate in the design and plan of the estate. What resulted has become an icon of 20th Century architecture. ‘We would emphasise the personal artistry which pervades the whole. It is this which gives Byker the quality of delights so conspicuously absent from most housing developments of the past 30 years’5. Redevelopment was only brought to a halt in the early 80s under the Conservative Government as their economic priorities came into effect. Social housing provision was severely curtailed. Byker is the largest example of Erskine’s work and is one of the finest example of large scale domestic urban architecture in Europe, if not the world. Approximately 2,500 housing units were constructed between 1970 and 1982. These were all owned and managed by the City Council and covered an area of 200 acres (81 hectares). 6 ‘… the most spectacular and unequivocally successful British housing development of recent times’ . Resident Participation in the Redevelopment Process There were concerns around the experience of community participation as far back as the 1970s. In 1977 Peter Malpass (Malpass, Peter 1977) was commissioned by the Department of the Environment to carry out research on the ‘urban redevelopment project at Byker’. He found that ‘unless local groups can exert effective political pressure, the amount of power relinquished by the authorities will be slight’ and that ‘for participation to be successful from the public’s point of view it is necessary to oppose the authorities’ tendency to organise the process in 7 ways which result in minimal redistribution of power’ . One such example was the ‘liaison committee’ set up in 1973 to provide ‘a regular forum for officials to put their point of view across and for residents to register comments and complaints. But what was not established in Byker was any kind of formal participation machinery. The liaison committee had no official recognition, status or delegation of power. It did not make any decision, nor did it have any right to be consulted on policy issues’. ‘In Newcastle the corporation was quick to respond to requests for greater public involvement in redevelopment, and as a result the people of Byker have had participation on the council’s terms and in the forms established by the council. Thus it is important to scrutinise official offers of participation because these are likely to involve the public in maximum exposure to the official point of view, but giving them little opportunity to influence decision making’. ‘In fact, public participation should be seen as a means of discovering and understanding conflicting views and interest within the community. By offering participation for the public in Byker, the corporation not only gained the initiative in defining the course that participation would take, but also demonstrated its intention to develop the area in co-operation with local people’. Malpass found that ‘The more the authorities pursue participation and promote an atmosphere of agreement the less the possibility of active public involvement. Consensus is the enemy of participation…Successful participation requires the recognition of the legitimate and inevitable conflicts of interest which arise during, for example, housing redevelopment in an area’. He concluded ‘Participation is all about power and politics. I have tried to show that unless interest groups are able to mobilise political skills and weight then the chief beneficiaries of participation will continue to be the authorities. We cannot expect to get a say in decision making just by asking for it. Power has to be won and unless some power is established in the hands of the rank and file, public participation will continue to be a tool of management rather than an extension of democrac.8.’ In the early 1980s this model Scandinavian housing development contained a population that then went through a period of dislocation – mass unemployment, run down in services and the flight to the 3 suburbs by those who could afford to move to private housing. What was left behind was a population with low education attainment, low employment skills, high incidents of ill health and low aspiration. This resulted in increased concentrations of poverty, disadvantage and exclusion from employment and education along socio-economic lines. BYKER TODAY: Population Details Figures from the 2001 Census that the profile of the Byker Ward is: Resident population: 8,200 Households: 4,171 Ethnic group population: 95.4% White People of working age with long term illness: 25% Average household size: 1.9 Household and Family Types One person Lone parent and dependent children 49.7% 9.2% Household Tenure Local Authority rented 58.3% Out of a total of 2,433 units 2,027 are in the Byker Redevelopment Privately Rented 6.9% Owner Occupied 27.2% Car Ownership Households with no car 68.5% Economic Activity (% of aged 16-74) Economically Active Male 58.9% Qualified Residents (% of all aged 16-74) Level 4/5 No qualifications 11.7% 47.6% Female 46.6% Resident Participation: Community Development Theory In order to discuss the engagement of residents in any initiative that is aimed at their participation the standards involved in community development work should be noted. The National Occupational Standards in Community Development Work (February 2002) state that: ‘the key purpose of community development work is collectively to bring about social change and justice, by working with communities to: Identify their needs, opportunities, rights and responsibilities Plan, organise and take action Evaluate the effectiveness and impact of the action All in ways which challenge oppression and tackle inequalities’. Values in community development work include: ‘Social Justice: working towards a fairer society which respects civil and human rights and challenges oppression Self-determination: individuals and groups have the right to identify shared issues and concerns as the starting point for collective action Working and learning together: valuing and using the skills, knowledge, experience and diversity within communities to collectively bring about desired changes Sustainable communities: empowering communities to develop their independence and autonomy whilst making and maintaining links to the wider society Participation: everyone has the right to fully participate in the decision-making processes that affect their lives Reflective Practice: effective community development is informed and enhanced through reflection on action’. With respect to Sustainable Communities: the Practice Principles include: 4 Promoting the empowerment of individuals and communities Supporting communities develop their skills to take action Promoting the development of autonomous and accountable structures Learning from experiences as a basis for change Promoting effective collective and collaborative working Using resources with respect for the environment With respect to Participation: the Practice Principles include: Promoting the participation of individuals and communities particularly those traditionally marginalized/excluded Recognising and challenging barriers to full and effective participation Supporting communities to gain skills to engage in participation Developing structures that enable communities to participate effectively Resident Participation: The Practice There are many community organisations in Byker, including informal networks that are encouraged by the design of the estate. The community meetings list is almost endless: the Byker Community Forum, the Byker Community Security Initiative, the Byker Environmental Forum, there are three active residents associations and the Byker Ward Sub Committee. For the East End of Newcastle there is the East End Community and Voluntary Sector Forum. On paper there appears to be a high level of participation by residents in the voluntary and community sector. Further research into the composition of meetings and group membership shows a very small minority of residents engaged, often the same small number of people who spend their voluntary time and effort and are often called ‘resident representatives’. This can appear impressive, but closer study of tenant participation in the social rented sector (for example Cole et al, 2000) reflects general apathy, a small number of residents prepared to be actively involved and concern about motives of those who did. For example if a resident is listed as attending a meeting, does this reflect that they fed the information back to their group or that their group debated the issue, or even that the information was understood or adequate for their needs. Along side these are the professionals – housing, cleansing, maintenance, regeneration, health, education, community workers, police, street wardens that often far outnumber the residents at meetings. Paid professionals, none of whom live in the area. Regeneration money is spent ‘on’ the area, but how much of it stays in the area? Which one is responsible for ensuring that the information is relayed back to the wider community – the paid officer or the voluntary community representative? Which one has the time to fully understand the issues being debated – the officer employed to facilitate a project or the community volunteer with lesser understanding of specific issues and often balancing demands such as work and childcare? In Byker a decreasing number of residents are involved in numerous groups discussing the same issues over the years with little or no result to show for it. Local Strategic Partnerships: The Newcastle Partnership and The Newcastle Plan The Newcastle Partnership is a multi-sector Local Strategic Partnership (LSP). It involves the public sector, the private sector and community and voluntary organisations. Local Strategic Partnerships outline how services will be delivered in communities the 88 most deprived local authorities in England, including Newcastle upon Tyne. Partners involved in the Newcastle Partnership work together to identify key targets and outcomes and this is outlined in The Newcastle Plan. The Newcastle Plan includes the “Local Neighbourhood Renewal Strategy”. This sets out how Neighbourhood Renewal Fund (NRF) will be spent in certain areas of the city. LSPs will be where many of the major decisions about priorities and funding will be taken. The aim of the Newcastle Plan is to outline how services will: Involve everyone and provide opportunities for all Make everyone safe See that people are healthy and cared for Create jobs Create homes where people want to live Regenerate disadvantaged areas The Community Empowerment Fund The Community Empowerment Fund (CEF) is a Government initiative that aims to support the community sector to fully take part in Local Strategic Partnerships. The CEF is designed to support Voluntary and Community Sector involvement in LSPs with the aim of ensuring representatives will be 5 equal partners. The Voluntary and Community Sector must be represented on the LSP both as service providers and as representatives of their membership and/or wider community. A £36m fund has been available since the summer 2001 for local people to get involved in revitalising England's poorest neighbourhoods. This fund aims put local people at the heart of the local regeneration process - giving them a direct say in the future improvement of their neighbourhood and its local services as set out in ‘A New Commitment to Neighbourhood Renewal: National Strategy Action Plan’. Newcastle Healthy City Project In 2001 Newcastle Healthy City Project was awarded the contract from Government Office North East (GONE) to develop the Community Empowerment Fund (CEF) in Newcastle. GONE has provided an annual grant of £155,000 to the CEF for the past two years. The government has announced that funding will continue at this level until March 2006. A Community Event was held in March 2002 to find out how Newcastle's communities wanted the CEF to develop. At this event members of the community sector voted on what the priorities should be: A Grants Fund: community sector can apply to run projects A Training Fund: to train Community Voices for the Newcastle Partnership to help them to participate fully Build a Community Network and reach out to 'marginalized' communities to be part of this network Provide support to Community Voices on the Newcastle Partnership The Principles of the Newcastle Community Empowerment Fund are: committed to supporting communities to participate in the Newcastle Partnership to build on what already exists open and transparent inclusive of communities who are often excluded to encourage participation by making processes simple committed to building a wide Community Network practical to actively promote equal opportunities 'Communities need to be consulted and listened to, and the most effective interventions are often those where communities are actively involved in their design and delivery; and where possible in the driving seat' (Social Exclusion Unit, 2001, 19). Community Participation: The Reality Two recent initiatives in the Byker Redevelopment have invited participation by residents. These are the introduction of Closed Circuit Television Cameras and the Byker Urban Design Competition. Closed Circuit Television Cameras: Closed Circuit Television Cameras (CCTV) permits the collection of images which are transferred to a monitor-recording device and permits them to be watched and stored. It allows remote surveillance and post-incident analysis. As stated on the cctv.com.ph website ‘The most significant driving factor causing this CCTV explosion has been the worldwide increase in theft and terrorism and the commensurate need to more adequately protect personnel and assets.’ CCTV has been on the agenda on the Byker estate for over 6 years. The reaction to a series of ‘antisocial’ incidents and youth disorder over several years was to introduce CCTV cameras to a particular housing block to monitor an area of shops and community facilities in 1999. This resulted in the movement of the action to the back of the cameras to a small and intimate communal area of housing. The resulting vandalism and harassment resulted in the eventual movement of tenants out of the area and the block was scheduled for demolition by the Council Authorities. As this block was one of the most architecturally significant examples of the work of Erskine there were calls from some residents and architectural professionals to protect the building. This resulted in a high metal security fence being installed around the block where it remains to this day. The block is still uninhabited. 6 A group of residents and officers from the council and police set up the Byker CCTV Group in December 2001 to progress the bid for wider installation of cameras on the estate. The group met for a series of 18 meetings until December 2003. Invitations to meetings were circulated to residents groups. Meetings were held at 1pm on weekdays. This group’s remit was to work in partnership to bid for funding and agree locations of 8 CCTV cameras at external, ground level locations across the estate. As part of the Home Office bidding process it was identified that the Byker CCTV Group needed to obtain local information about crime concerns and support for CCTV in the area. A questionnaire was delivered to all the houses in the redevelopment (approximately 2,500) in two phases in July and August 2001. A total of 140 responses were received. (Information from Capital Investment to Respond to Letter of Complaint from Rabygate Residents. Newcastle City Council). Question 3 of the Questionnaire asked ‘Do you think CCTV cameras may help to reduce this problem (of anti-social behaviour)? 94% of respondents said yes, 2% said no and 4% were unsure’. As a result of this questionnaire the author of the report concluded that: ‘This shows an overwhelming number of residents returning questionnaires were in support of CCTV camera cover for their area.’ Question 4 asked residents ‘Would you come to a meeting to discuss this more fully?’ 78% of residents returning (the) questionnaire said yes showing a willingness to participate in the process. It is interesting to note the actual numbers of residents actually participating in the process – on average four residents at each meeting. In the Conclusion to the report prepared to accompany the CCTV bid the author states: ‘The results of the questionnaire shows that those residents that responded experience anti social behaviour, crime and fear of crime and are overwhelmingly in support of CCTV cover in the Byker Redevelopment area.’ It is worth noting that 140 out a total of 2,500 houses returned a questionnaire. This equates to 5.6% of the homes in the Byker Redevelopment. The Minutes of the CCCTV Meeting on 3rd December 2001 indicate that Concierge funding was rd discussed at this early stage. It was not until 23 April 2003 that a letter was sent from the Capital Investment Section to all residents in the Byker Wall informing them of the concierge project details and that a rent increase would be incurred (although the exact cost was not stated as it was being assessed). From the Minutes of the CCTV Group Meetings it was noted that representatives came from Northumbria Police, Housing Investment, the Neighbourhood Housing Office, Byker Street Wardens, the Community Development Centre and residents groups in the low rise estate. There was no representation at the meetings from residents living in the housing in the Wall that would be recipients of the Concierge services. CCTV Meeting on 5th May 2003: Proposed location of 8 external cameras available for comment at the local Housing Office. No mention was made of surveillance cameras being installed in the Wall. rd CCTV Meeting on 3 June 2003: the Minutes indicated that the initial proposed rent increase for Concierge services would be £10 for residents living in the Wall. Residents in attendance requested that rent increase should be phased in over a period of time as a sudden increase may discourage employed residents to leave. Residents were informed that people on benefits would not have to pay the increased charge. Six residents of the estate were in attendance at this meeting, of these two were residents of the Wall. CCTV Meeting on 8th July 2003: The Minutes indicate that the rent increase had been referred to the Directorate Coordinator at the Council and that rents could be increased over a number of years eg £2 in the first year. One resident of the estate was present at this meeting, no residents of the Wall were in attendance. th CCTV Meeting on 9 September 2003: Letter sent informing residents of the Wall informing them that there would be a rent increase and it would be phased in over a period of time. The immediate charge would be £4, then £2per year as rent charges increase. The records of this meeting also state that the 8 external cameras would cost £125,000 and additional cameras would be £30-50,000. A note was also made that there was also a ‘need for further resident involvement to show support for any future 7 funding bids.’ One resident of the estate was present at this meeting, no residents of the Wall were in attendance. th CCTV Meeting on 13 November 2003: The rent increase of ‘£9.50 was discussed for Wall residents over a phased basis. £4.00 in the first year. Residents felt that this was a bit steep, especially those struggling to manage now, feel £2.00 a year would be fairer.’ th CCTV Meeting on 24 November 2003: Letter to residents advised that increase would be notified by Rent Assessment section. 15th December 2003: Rent increase notice sent out by Rent Assessment. Also at CCTV Meeting concern was again raised about the ‘difficulty of residents meeting increase raised.’ Five residents of the estate were at this meeting, no residents of the Wall were in attendance. This resulted in Home Office funding for 100 cameras installed to monitor 500 homes in the high rise housing in January 2004. Generally this meant that cameras were installed at each end of the access decks, one camera was installed in each lift and a camera was integral to each of the 16 main external entrance doors to the building. The scheme was also linked to a CCTV scheme already in operation on the estate that consisted of four cameras. There was no consultation with residents living in the housing blocks and details of the scheme were not shown or explained to them. Residents came home to find cameras monitoring their social space. Cameras appeared overnight with speakers and listening devices to monitor the communal spaces. In areas where neighbours formerly congregated they now felt uncomfortable. The cctv.com.ph website notes that ‘Critical to the success of CCTV is involvement of the community in the decision-making process. By making sure that the community wants CCTVs to be used to protect them, “Big Brother” objections are much less likely to surface’. Some residents active in one resident association objected to the imposition of surveillance cameras in th their social space. In response Capital Investment produced a document dated 26 January 2004 (Author unknown) outlining the process that they have been involved with. This stated: ‘Position for walkway camera’s (sic) were selected by Officers on the basis of ensuring maximum coverage. The aim was to ensure when selecting the positions for these camera’s (sic) if unauthorised access was gained to the building the person could be monitored and tracked within the wall. It is not uncommon once a system is up and running to move the camera’s (sic) to alternative locations if the original location is found not to give the maximum coverage. This walkway could be monitored over the initial months of the concierge and if it is felt the camera’s (sic) could be better located then this can be organised.’ The local housing office sent leaflets to each of the flats asking if the residents wished for the cameras to be removed. A slight majority of residents were in favour of removing the cameras and relocating them in the two entrance foyers to the block to monitor people entering and exiting the building. The ensuing debate about the removal of cameras caused some conflict amongst neighbours in such a communal space. Fear of crime was used to justify the instillation cameras with Street Wardens proposing that residents would be to blame ‘if an old woman is mugged on your landing’. No such incident had happened in the 30 years since the Wall was built. The Home Office Research Study 292 ‘Assessing the impact of CCTV’ (Gill, Martin and Spriggs, Angela, 2005) found that: Crime reduction was most successful in car parks Residential areas showed varied results, with crime going down in some areas and up in others Residential redeployable schemes appeared to show no long-term reduction in crime levels. Impulsive crimes (eg alcohol related crime) were less likely to be reduced than premeditated crime Violence against the person rose and theft of motor vehicles fell That CCTV is more effective in sites with limited and controlled access points, such as entrances and exits to the area Residents who were aware of cameras worried more often about becoming a victim of crime 8 Level of support for CCTV remains high amongst residents, although the proportion of residents happy with having cameras in their area decline after their installation The existence of funding for CCTV created pressure to bid for it, often in the absence of reliable intelligence indicating where CCTV would be likely to have most effect. Where statistics were gathered, they were sometimes inexpertly produced or were even distorted, having being compiled to support a bid It is worth noting from the Minutes of the Meeting of the Byker Community Safety Meeting held on th 14 March 2005 that ‘Police noted that the CCTV was of benefit to them. Criminality has moved from the areas of CCTV. It is now our (sic) of cameras range…Police noted that the original bid didn’t take into account the fee for the cables as well as 15 cameras. Only 8 were afforded and linked to the concierge. The Political Agenda has changed since then and CCTV is given less importance’. (Author’s emphasis). The CCTV initiative was set up under Home Office Crime Reduction Programme and £170 million has been made available to fund programmes since 1998. Byker Design Competition: Bridging NewcastleGateshead is one of nine housing market renewal pathfinders set up by the Britsh government to tackle the issue of low demand housing by involving local communities, the private and voluntary sectors to rejuvenate the local housing market. A 15 year programme covers 77,000 homes across Newcastle and Gateshead. £73 million from the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister has been allocated to support work until March 2006. The Newcastle Gateshead Pathfinder website (http://www.newcastlegatesheadpathfinder.co.uk) states: ‘The changing needs and aspirations of local people will shape the development of liveable communities, where residents will benefit from increased housing opportunity and choice in lively, cohesive neighbourhoods that provide the best quality of life in a healthy, safe and sustainable environment. Some of the key targets that we want to meet include: Reduction in the number of vacant properties A rise in house values, in line with the regional average Increase in home ownership Increase in the number of new homes built Increase in the quality of housing Increase in neighbourhood satisfaction Improved neighbourhood perception Improved confidence amongst residents Increase in urban spaces With help from our partners we want to: Reduce the amount of crime Improve educational achievement Increase the number of local jobs Increase the number of businesses Improve life expectancy Improve access to services’ In order to improve the housing market in Byker the City Council proposed an Urban Design Competition funded by Bridging Newcastle Gateshead and the European Commission European Regional Development Fund and INTERREG III (a European Commission Community Initiative to encourage transnational co-operation on spatial planning). Community involvement was acknowledged to be important at an early stage of this project. Under new legislation a Statement of Community Involvement (SCI) was required to set out the planning authority’s policy for involving the community in the preparation and revision of Local Planning Documents and Planning Applications. The British Government’s principles for community involvement are: Involvement that is appropriate to the level of planning Front loading of involvement Using methods that are applicable to the communities involved Clearly identified opportunities for continuing involvement as part of a continuing programme of consultation 9 Transparency and accessibility of the process Planning for involvement: community involvement should be planned into the process of preparation and revision of documents The procedure for verifying the soundness of the SCI matches a series of categories that the SCI must meet: Compliance with the minimum requirements for consultation Linkages with other community involvement initiatives Identification of the community groups and other bodies that will be consulted Methods of consultation are suitable for the guidance and groups involved Proof that resources are available to manage community involvement Illustration of how the results of community involvement will be fed into the plan preparation stages As part of the assessment of community involvement in the Byker Design Competition Newcastle City Council commissioned a report from the University of Newcastle (Coaffee, John and Brocklebank, Chris 2005). The results of this can be compared to a document developed by Yorkshire Forward, the Regional Development Agency for the Yorkshire and Humber region. Yorkshire Forward have been proactive in developing community involvement and empowerment in regeneration. Their ‘Active Partners Report: Benchmarking Community Participation in Regeneration’ (Yorkshire Forward, March 2000) outlines ways of assessing community engagement. Under the following headings highlighted by Yorkshire Forward to be essential to community participation, the comments in italics are from the report on community participation in the Byker Design Competition. Influence Byker Residents representatives ‘did think that the ultimate decision would not be up to them and irrespective of their views and opinions, Councillors and Officers would have the final word’. Inclusivity Residents had ‘concerns regarding the apathy that many members of the community had shown the scheme and they hoped for ways that this could be improved’. The report states ‘there is a lack of structure to the techniques being used. A lot of the consultations have been rushed and obvious mistakes have been made that have had a detrimental effect on the quality of the feedback received… Hard to reach groups…have been largely ignored.’ Communication Residents strongly felt that ‘there were too many time delays in receiving information that they requested. They considered this to be unacceptable and if they were expected to put the effort into attending meetings and promote the competition, the least Newcastle City Council could do is acquire reports for them within a set time frame.’ The report states ‘Communication between the community and NCC is not as clear as it has to be to ensure the smooth and efficient running of a scheme of this nature’. Residents’ inability to communicate to the wider community the details of the project ‘is a direct consequence of NCC’s current short comings with passing on information and making minutes available as well as simple tasks such as briefing residents groups prior to meetings…’ Capacity Residents expressed the view that ‘if funding and capacity (building) wasn’t available to make the scheme a success then Newcastle City Council should not have began in the first place’. The report states that ‘Funding is lacking with respect to developing the knowledge and understanding of the residents group’. It was noted that ‘Capacity and resources was mentioned and the community resented the fact that funds were available for practices, yet as so called ‘equal partners’, they had insufficient funds available to develop and effectively contribute’. In conclusion the report states that overall ‘the approach to community engagement seemed too far ad hoc and lacked any clear strategic direction or focus. As a consequence it was accused of being ‘top down’. CONCLUSION Sustainability in housing is vital to the regeneration of communities. The British government has made it one of its priorities to encourage the renaissance of cities, especially in the North of England. This has been a partnership between national government, regional organisations and local bodies. However, 10 it is vital that the regeneration of neighbourhoods prioritises the development of the residents in those communities that are suffering from a lack of demand. Funding can and should stimulate tangible changes such as housing renewal, urban planning, economic development and social facilities but if the residents of the neighbourhood are only used as a lever for funding and are not equal partners in the regeneration process then there is no regeneration apart from that on a superficial level; the same problems with unemployment, crime and maintenance will continue and the improvements will not last. As has been outlined in the examples used in this paper national and local organisations can be reluctant to fully engage local residents, or do not have a well structured and accessible long term programme that encourages excluded members of a community to participate on their own terms and to their own abilities. For initiatives to be successful in the long term the community needs to be able to develop its own resources and programme its own exit strategy once the professionals have moved on to their next project. ‘People really do sit on the benches and drink tea together. A place to be homesick for, a place to come 8 home to.’ 1 Anon. (1963) Development Plan Review. City and Council of Newcastle upon Tyne. 2 Erskine, Ralph (1970) Report on the Byker Redevelopment. City and Council of Newcastle upon Tyne. 3 Colqhoun, Ian (1999) Architectural Press 4 Evening Chronicle (1974, 7 February), p13 5 Ambrose Congreve Award Assessors Report (1980) 6 Saint, Andrew (1977, 20 May) New Statesman 7 Malpass, Peter (1977) Community Participation, The Byker Experience 8 Ravetz, Alison (1976, 14 April) Architects Journal References: Coaffee, J. and Brockelbank, Chris (2005) Developing a Statement of Community Involvement. Global Urban Research Unit, University of Newcastle. Cole I., Hickman P. Millward L., Reid B., Slocombe L. and Whittle S. (2000) Tenant Participation in England: A Stocktake of Activity in the Local Authority Sector. Sheffield: Centre for Regional, Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University. Malpass, Richard Who Benefits From Public Participation? Community Action No 35, JanuaryFebruary 1978. Department of Economics & Social Science, Bristol Polytechnic, August 1977. Martin, Gill and Spriggs, Angela Assessing the impact of CCTV, Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate, February 2005 Power, Anne and Mumford, Katharine The slow death of great cities? Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 1999. Unknown (2004) Information from Capital Investment to Respond to Letter of Complaint from Rabygate Residents. Newcastle City Council. Yorkshire Forward, March 2000 Active Partners Report: Benchmarking Community Participation in Regeneration Websites: CCTV.com.ph http://www.newcastlegatesheadpathfinder.co.uk http://www.newcef.org.uk/ 11