Theory and History of Housing

advertisement

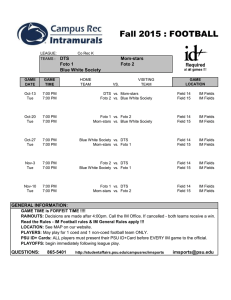

1960-1980: Critical voices I 15. September 2014 - Eli Støa Contents • Ideological confrontation • International ideas – Alternative utopies: Situationism – Open form / Structuralism / Flexibility – Alternative to high rise: Low / dense – Community / Participation Critique • Changeability • Individual influence • Privacy – community • Low – dense • User participation Issues • Ideological confrontation • International ideas – Alternative utopies: Situationism – Open form / Structuralism / Flexibility – Alternative to high rise: Low / dense – Community / Participation Alternative utopies: Situationism (1960s) • utopian, revolutionary ideas where changeability played an important role : ”ephemeral, temporary, multi-interpretable architecture” (Bosma, 2000:46) • Open spaces in the city should offer situations for action and activities • Confidence in the creativity of the masses • the nomadic life • the dynamic labyrinth: ”the occupier as the producer of space. The architect has, at most, a supporting role as an intermediary between consumer and producer” (ibid:52) ’New Babylon’ Constant Nieuwenhuys (1971) “..the city is an artificial landscape built by human beings in which the adventure of our life unfolds.” Constant Nieuwenhuys, 1960 ‘New Babylon’ Constant Nieuwenhuys (1971) ”The act of creating is more important than the product created, and the act of travelling outweighs arriving at one’s destination. Life has the features of a road movie” (Bosma, 2000:51) Archigram • Walking city • Plug-in city • Instant city © Ron Herron, Archigram Courtesy Ron Herron Archive Archigram • Walking city • Plug-in city • Instant city Peter Cook (1964) Archigram • Walking city • Plug-in city • Instant city © Ron Herron, Archigram Courtesy Ron Herron Archive Learning from the vernacular «The use of single building types does not necessarily produce monotony» (Rudofsky, 1964: 55) Bernard Rudofsky (1964): «Architecture without architects» Portable roof, Cherrapunji – India (Rudofsky, 1964: fig 142) «The mobile home of vernacular architecture offered a figure of domesticity not tied to the ground or captured by administration and commercialism, one that might sustain both respect for the environment and offer a space of dwelling» (Scott, 2000:231) Open form – Oskar Hansen ”Hansen developed the theory of ’the open form’, an architecture which should open up for changed use, new forms as well as individual interpretations” (Guttu, 2003:224) Området Slovackiego i Lublin, Polen er Oskar Hansens eksempel på åpen form (Guttu, 2003:235) Open form – Oskar Hansen Three objections against functionalism (according to N O Lund): 1. That individual need are not sufficiently considered - Some decisions should be left to the individual, the product should be possible to adapt to specific needs 2. That changing needs and user patterns are not sufficiently considered - It should be possible to supplement or substitute existing functions with new ones within the same structure 3. That architecture was adapted to a specific way of life (formal critique) - It should be possible to add new forms without disturbing the (aesthetic) totality From ”På sporet af den åbne forms elementer”, lecture by Oscar Hansen (adapted from Lund, 2001:62-63) Open form – Oskar Hansen Example of Open Form: Slovacki housing estate in Lublin (Hansen, 2005) Kystmuseet i Sogn og Fjordane, 1985 «I vår tid tyder Open Form arkitektonisk frigjering» «In our time Open Form means architectural liberation» (Svein Hatløy, 2009: http://openform.wordpress.com/2010/12/10/open-form-50-ar/ http://hoff-andersen.blogspot.no/2010/05/visit-to-mr-hatloy.html Supports – N J Habraken • Separation between ”support” and ”infill”: Fixed vs changeable • User and residents should have influence on their home environment • • Production of houses involve several actors and professions The meeting between different technical systems should be designed in a way which makes it possible to replace one system with another with a similar function • Architectural Press, 1972 Acknowledging that the built environment is continuously changing Source: http://www.habraken.com/html/introduction.htm ”..a systematic division between elements defined by the designers and mass produced commodities / products among which the users could choose ” (Guttu, 2003:224) Habitat 67, Montreal. Architect: Moshe Safdie Skjettenbyen, Skedsmo (1969-73) Arch: Skjettenprosjektering: Nils-Ole Lund and Hultberg, Resen, Throne-Holst 1050 terracced housing, 600 flats Rational production / elements: modules 3x3m User participation: Half of the houses are extended Structuralism in Norway • Residents regarded as an individualised diversity – not only as member of a standard nuclear family • A new role of planners introduced, their task was more organisation and adaption rather than designing all details • Idea of users’ co-determination • Low-dense structures as alternative to both detached houses and high rise buildings Hultberg & Seablom (1966-7) (adapted from Guttu, 2003:225) Structuralism in Norway Preconditions • Mass production – unknown users, the dwelling had to be adapted after completion • Without predefined assumptions – redefinition the basic housing needs – aiming to break with locked-in conceptions • Trust in technology – possibilities for equality and creativity among residents • The strict physical structure – a condition for individual display – within the restrictions of the totality (Guttu, 2003:226) Critique • Technologically based flexibility / system thinking results in a mechanistic architecture without deeper meaning (Svein Hatløy) – Structuralism led to formal dictate – ”Diligent variations” instead of ”new situations” – Lack of architectural qualities which could have provided people with possibilities for rich experiences, use and interpretations of a diversity of situations (Guttu, 2003:234) Critique • Generality more important than flexibility – Opening for functional interpretation (Ola Mowé) • Polyvalancy: – A term introduced by the Dutch architect Herman Hertzberger in 1962 meaning that architectural space can be used in different ways over time or in different situations without having to undergo physical changes –. Privacy and community – hierarchical thinking • Urban – Public • • Urban – Semi-Public • • Group – Public • • Group – Private • • Family – Private • • Individual – Private From Chermayeff & Alexander (1963): ”Community and privacy” Privacy and community – hierarchical thinking ”We are interested, principally, in establishing the integrity of those places where the smaller human scales of immediate experience are possible” Chermayeff & Alexander (1963: 121) Privatlig og offentlighet – hierarkisk tenkning Siedlung Halen, Bern Atelier 5 (1961) 80 terracced houses surrounding a common square • • • Planned by a group of intellectuals in Bern Formal associations to purism of the 30s + vernacular villages Common spaces: pool, greens, heating central, petrol station, café, shop • • The surrounding woodland – commonly owned Concentrated built structure – alternative to the suburbs • Hierarchy private – semi private – common Dalen Hageby, Trondheim Foto: Tore Brantenberg Jarle Øyasæter, 1961 Foto: Tore Brantenberg Foto: Tore Brantenberg Foto: Tore Brantenberg Meek Borettslag, Molde NBBLs arkitektkontor v/Torstein Ramberg (1978) Foto: Mette Sjølie Source: www.mobo.no Kilde: www.mobo.no Foto: Mette Sjølie Foto: Mette Sjølie Cultural shift in the 1970s From To – Universalism, optimism for the future and trust in the technological ability to solve societal problems – Small scale, historical models, alternative technology – Increased focus on ”life between buildings” and the community – Focus on housing standard: functional plans and indoor family life – ”Small is beautiful” – Large scale – Cultural heritage – Adaption to place (Jon Guttu, 2003) From high rise to ’low-dense’ •The Ammerud report (Byggforsk 1969-71): Critical to the residential quality – in particular for children •”Urban planning costs” (NIBR, 1969): Not economically profitable to build higher than 3-4 fl User participation • An objective in its own right • Direct dialogue – adaptation after completion is not enough • On the residents’ terms Sherry Arnstein’s ”Ladder of participation” 1969 Carsten Hoff & Susanne Ussing: ”Alternative architecture” Louisiana 1977 Kilde: Nils Ole Lund, 2001:167 • Demolition / renewal of worn down tenements for workers • Large degree of participation e.g. through the establishment of an architectural office within the neighborhood • 2317 dwellings • 80 % terracced houses, 20 % flats in the ”Byker Wall” • 7-8000 people Source: Egelius, 1988 “…to maintain, as far as possible, valued traditions and characteristics of the neighbourhood itself…The main concern will be for those who are already resident in Byker, and the need to rehouse them without breaking family ties and other valued associations or patterns of life.” Ralph Erskine, source: http://municipaldreams.wordpress.com/2013/03/19/thebyker-estate-newcastle/ Source: Egelius, 1988 ”Byker for the Byker people” • • Complete and integrated environment • Low cost, collaboration with residents Maintain existing traditions and characteristics • • Exploit the physical character: slope, view, sun • • Rehouse those already living in Byker Complete system of pedestrian routes Provide a character / a recognizable physical form, local individuality to each group of houses Source: Egelius, 1988 «It was a lovely place to live. Now it’s changing. People don’t feel safe anymore» (Resident’s view, BBC 2007) Source: Egelius, 1988 Selegrend 1, Bergen CUBUS AL Architects: Odd Løvset & Nils Roar Øvsthus (1974) Photo: Steinar Anda Seletunstiftelsens målsetning: • Enkeltmennesket skal kunne influere på sin egen boligsituasjon • Boligområdene bør gjenspeile det samfunnsmessige gjennomsnitt mht kjønn, yrke, sosial status, m.m. • Boligområdet skal planlegges for samarbeid, fellesskap og sosial kontakt • Gjennomsnittsmennesket har et sosialt ansvar for dem som ressursmessig er dårligere stilt (Martens (2000): Århundrets Norske boligprosjekter) ”..drømmen om de sæle grender” (Brantenberg, 2002) Photo: Tore Brantenberg Photo: Tore Brantenberg