Utilization of Activity-Based Costing System in Manufacturing

advertisement

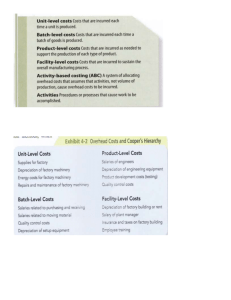

International Review of Business Research Papers Vol.6, No.1 February 2010, Pp. 1-17 Utilization of Activity-Based Costing System in Manufacturing Industries – Methodology, Benefits and Limitations1 Boris Popesko2 The subject matter of this paper is the detailed consequences of putting in place an Activity-Based Costing system and its structure within the manufacturing industry. Moreover, it defines steps within ABC application, as well as analyzing the input and output information and data required for effective utilization of the system. The close bond between cost allocation methodology and application procedures is also determined within this work, thereby describing all the features necessary for effective ABC implementation. The results published herein come from research projects run over a 3-year timeframe, ones focused on the methodology of implementing an Activity-Based Costing system and its resultant influence on the efficiency of manufacturing businesses. The author has conducted a number of ABC system applications in manufacturing industries in order to gather the data and information necessary to define application and allocation principles.The paper reveals two final outcomes. The first of these determines the methodology of building an ABC system, looking at the essential steps necessary to construct a system in an organization. The other describes cost allocation methodology, which is performed within separate stages of implementation.The major part of paper is dedicated to explaining the methodological steps within ABC implantation, which include a feasibility study and review, activity and cost object definition, assigning costs to activities, defining the appropriate cost drivers for individual activities, determining the output measures for individual activities, calculating the primary rates of individual activities, assigning the costs of support activities to primary activities, and calculating the costs of defined cost objects.One important issue that determines the eventual form and structure of the ABC system is senior managers’ demand for data utilizable for decision making. All these requirements need to be defined in relation to the structure of the system. An effectively implemented Activity-Based Costing system then provides accurate product costing and proves a useful aid for managing business operations. In the final part of paper, the results are discussed according to the all features of ABC application in the manufacturing industry. Field of research: Business Administration, Accounting Introduction The difficulty inherent in choosing a proper and accurate product costing method for manufacturing enterprises has been widely discussed by academics and practitioners. The important limitation of traditional (absorption) costing methods had been deeply discussed along with advantages of other costing method as Variable Costing or Activity-Based Costing (ABC). Despite the fact that issues relating to ABC have been widely discussed by researchers and practitioners in the past ten years, this modern concept still lacks general rules governing both methodology and cost The article is processed as an output of a research project Methodology of the Activity-Based Costing system implementation and its influence on the manufacturing industries efficiency registered by the Grant Agency of Czech Republic under the registration number 402/07/P296. 2 Boris Popesko, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Tomas Bata University in Zlin, Faculty of Management and Economics, Mostni 5139, Zlin, 760 01, Czech Republic, E-mail: popesko@fame.utb.cz 1 Popesko allocation principles. Looking back, the concept of Activity-Based Costing has been considered a sophisticated method of cost calculation since the early 1980s. The ABC method was originally designed as a solution to the limitations of traditional costing methods. The problems relating to these traditional costing methods had been discussed with the need for improvement in the quality of costing systems actually utilized in practice. However, one challenge faced when carrying out the cost allocation procedure in ABC lies in the manner in which the methodology is applied. When allocating costs in adherence to ABC principles, the user of the system also has to strictly follow the individual steps within the implementation methodology, where clearly defined allocation procedures and other methodical acts are performed. This research study has no ambitions to judge the expediency of the ABC system for recent or future users. In fact, the aim of this paper is to definitively explain the necessary steps to apply ABC, as well as to clarify procedures for activity output measurement and cost assignment. The paper also describes the benefits and limitation of ABC implementation in manufacturing industries. 1. Literature review 1.1 Elementary principles of the Activity-based approach The ABC concept was designed as a method which eliminates the shortages of the traditionally used absorption costing methods. Traditional costing techniques were used for the purposes of overhead cost allocation during the 20th century. These are based on simplified procedures using principles of averages. In recent decades, such conventional concepts have become obsolete due to two major phenomena. The first of these is ever increasing competition in the marketplace, the necessity to reduce costs and the effect of having more detailed information on company costs. Secondly, there has been a change in the cost structure of companies. In terms of the majority of overhead costs, traditional allocation concepts, based as they are on overhead absorption rates, can often provide incorrect information on product costs. Those shortages or limitations had been very closely described in the scientific publications (Drury, 2001), (Lucas, 1997). The first criticism of traditional costing concept was published by Kaplan and Johnson in (1987). The effect that plays a role in determining an inaccurate overhead cost allocation could be described (figure 1) as ‘averagization’ (Popesko, 2008). In other words, the end results of allocating a proportionally average volume of costs of any type to all cost objects. For example, the cost for transporting an item to customer A is the true value of 50€, and transport to customer B is 900€. If we use traditional absorption costing, the transport costs will become part of the sales or distribution overhead, meaning all the costs of this type will be mixed together and then allocated through the absorption rate to the cost object, in proportion to the specific type of direct cost. All cost objects then will be subject to the principal average volume of transport costs. In the example this means 130€ for customer A and 110€ for customer B.3 Above mentioned problems could be sometimes be solved by application of differentiation absorption costing, which uses several types of overhead with different allocation The difference is caused by the different level of direct costs of product A and B. If the direct costs are the same for both customers, and both customers order an identical product, the transport costs for both products will also be same – the average amount. This example shows the injustice of incorporating the relation of direct labour cost volume to trade or transport cost allocation. Direct labour and transport or trade costs usually bear no relation to each other. 3 2 Popesko bases, instead of summing absorption costing with one universal overhead and one allocation base (Král, 2006). Another possible solution is the application of constcentre overhead rates instead of pland-wide rate (Drury, 2001). Despite that, the problem of what here is termed ‘averagization’, is also significant in companies with a very sophisticated system featuring cost centre overhead rates. Even if several different overhead rates for different overhead cost pools are used to improve the quality of cost assignment, the basis is still the same – the allocation base usually represented by any type of direct cost. If the basis is only set to the easily measured amount of direct costs, it is not possible to achieve accuracy in cost assignment, because the true causes of cost consumption frequently have a natural base. The absorption costing method could distort product costs because it allocates overhead costs proportionally to the portion of direct costs. Glad and Becker (1996), identified a number of fundamental limitations in traditional costing systems: • • • • Labor, as a basis for assigning manufacturing overhead, is irrelevant as it is significantly less than an overhead and many overheads do not bear any relationship to labor costs of labor hours The cost of technology is not assigned to products based on usage. Moreover, direct (labor) cost is replaced by indirect (machine) cost(s) Service-related costs have increased considerably in the last few decades. Costing for these services was previously non-existent Customer-related costs (finance, discounts, distribution, sales, after-sales service, etc.) are not related to the product’s cost objects. Customer profitability has become as crucial as product profitability In some instances, especially when a company has a very homogenous output, few departments with overheads and customers are very similar in nature, the simple absorption costing method should provide very accurate outputs, despite its limitations (Staněk, 2003). The absorption costing method boasts one very important advantage - it is very simple to put into utilization. All the information the user has to gather together can be found in accounting books or product material and labor sheets. Kim and Ballard (2002) defined the problems that can result from using traditional methods of overhead costing as: • Cost distortion hinders profitability analysis • Little management attention to activities or processes of employees 3 Popesko Figure 1: The ‘averagisation effect’ in the costing process Allocation process Real costs registered in the accounting system Costs allocated to product / customer in the costing system Transport costs Customer A 50€ Allocated costs Customer A 130€ Trade & Distribution Overhead All costs are mixed together Average portion of the overhead costs according to the volume of direct costs Allocated costs Customer B 110€ Transport costs Customer B 900€ Major difference between real and allocated costs The logical solution of registered disadvantages of traditional absorption costing systems was to develop a costing method which would be able to incorporate and utilize cause-and-effect instead of widely applied arbitrary allocation principles into the company costing system (Drury, 2001), (Lucas, 1997). In situation, when the portion of overheads exceeds 50% of total company costs and the company is using single measures for allocation of overhead costs to the cost objects, the risk of an incorrect product or customer costs calculation becomes significant. Following the 1970s, there was a general realization of the limitations in traditional costing systems. Greater competition and further inaccuracies in costing products effectively encouraged businesses to seek out alternative methods, ones offering far more transparency and enabling accurate and causal cost allocation. It was then, at the dawn of the 1980s that the Activity-Based Costing (ABC) method came about, being quickly adopted by enterprises of many and various types. The spread of ABC owed a significant debt to advances in computing and IT thereby permitting practical utilization of ABC principles. The Activity-Based Costing method is a tool which could bring about significant improvement in the quality of overhead cost allocation. The ABC process is able to incorporate both physical measures and causal principles in the costing system. The basic idea of ABC is to allocate costs to operations through the various activities in place that can be measured by cost drivers. In other words, cost units are assigned to individual activities, e.g. planning, packing, and quality control using a resource cost driver at an initial stage with the costs of these activities being allocated to specific products or cost objects in a second phase of allocation via an activity cost driver. 4 Popesko Activity-Based Costing methodology has been described, and further evolved, by many authors (Drury 2001), (Glad and Becker, 1996), (Kaplan and Cooper, 1998), (Staněk, 2003). The ABC process could vary from simple ABC, using only one level of activities to expanded ABC, comprising various levels of activities and allowing for mutual allocation of activity costs (Cookins, 2001). Nevertheless, it should be noted that the ABC approach is not a truly revolutionary or a completely new means of allocation. In essence, it has transformed the logical relationships between costs and company outputs entering a costing system. Indeed, ABC has incorporated logical allocation procedures from costing systems predating its own complex methodology. 1.2 Implementation methodology Together with the emergence of ABC methodology, issues relating to its practical utilization and implementation have been presented by both academics and practitioners. At this point, it is necessary to distinguish between two diverging approaches addressing ABC system implementation. The first considers implementation merely in terms of performing an ABC calculation and is primarily focused on the system’s construction, cost flow, and allocation procedures. Drury (2001), defined the necessary steps to set up an ABC system as follows: 1. Identifying the major activities taking place in an organization 2. Assigning costs to cost pools/cost centers for each activity 3. Determining the cost driver for every activity 4. Assigning the costs of activities to products according to their individual demands on activities These are described by other authors in a very similar manner. For example, Staněk (2003), considers adjusting accounting input data as the initial procedure in building the system. Furthermore, he prescribes the fourth step of implementation as calculating the activity rate, which is defined as an activity unit cost. The above-defined steps of system design could be considered as a very brief overview for successful implementation process. Some other authors define much more detailed application procedures. The steps in the ABC application methodology defined by Glad and Becker (1996) are: 1. Determine the nature of costs and analyse them as direct traceable costs, activity traceable costs and non-traceable costs (or unallocated costs) 2. Account for all traceable costs per activity, distinguishing between primary and secondary activities 3. Identify the company’s processes, activities and tasks, and create process flowcharts 4. Determine cost drivers for each activity and use output measures to calculate activity recovery rates 5. Trace all secondary activities to primary activities, so that the combined activity rates include all support costs 6. Identify which cost objects are to be priced. Compile the bill of activities for each cost object 7. Multiply the activity recovery rates by the quantity of output consumed as specified in the bill of activities. The sum of these calculated costs will give the activity-traced cost of the cost object 5 Popesko 8. Direct costs and non-traceable costs should be added to the cost calculated above to give the total cost of the cost object The other approach to ABC implantation not only encompasses the structure, design of the system, and tackles the question of how costs are allocated in ABC, but also deals with issues related to its implementation within an organization. In other words, the question of how the ABC system must operate within an enterprise. This approach considers all the necessary features that have to be addressed in the process of setting up an ABC system. Many authors have described implementation in great detail (Cokins, 2001), (Glad and Becker, 1996), (Innes and Mitchell, 1998). The procedures they analyze are far wider ranging than the steps involved in system design because of the focus on organizational, personnel, capacity, and effectivity issues of ABC system building and utilization. Probably the most important matter solved by this approach to ABC application, which analyzes performance during its set-up, is the question of the efficacy of the future system. ABC usually processes large quantities of financial and non-financial data. If we want to maintain the effectiveness of the system, it is necessary to ensure that costs for obtaining that kind of the data do not outweigh the benefits of the system. Should this not be possible, the application of the system is ineffective. Applying ABC brings different benefits for different organizations. According to the characteristics of the system, we can say that putting the system in place would be effective in organizations with a complex and heterogeneous structure of activities, products, and customers. Petřík (2007) describes organizations with the most to gain from ABC implementation as: • Those with a high frequency of different cost objects – this presumption is valid for either production companies, or for service or trading companies • Those with a large portion of indirect and supporting costs • Those with a great number of processes and activities 2. Research method conducted As the steps described when setting up an ABC system seem rather too general for practical usage, case studies were carried out so as to define the detailed characteristics of design and implementation. The resultant findings are based on three projects of full ABC system implementation conducted by the author’s research team in the past two years. The organizations selected for this purpose were three manufacturing companies from the plastics and automotive industries, all with a relatively complex structure of products, customers, and performed activities. Table 1 gives an overview of the case studies performed and the objects of these implementations. The quantity of product types and customers is continually fluctuating, so the figures in the table are estimated and approximate values. The number of activities represents the amount of the same as defined within the model, these being designated as either primary (p) or secondary (s) types. The relative portion of overhead costs could be interpreted as fairly low when taking into consideration the effect expected from implementing ABC (Petřík, 2007). The businesses in question handle a high quantity of semi-finished supplies and components, the value of which is considered as direct material cost. The effective management of overhead costs is desirable in spite of the final products being very sensibly priced with very low profit margins. 6 Popesko Table 1: Overview of performed case studies (own research) Case study/company Industry Number of employees % of overhead costs Number of product types Number of customers ABC MODEL Number of activities (p+s) 1 Plastics 96 24% 200 40 2 Plastics 429 16% 100 15 3 Automotive 500 25% 400 100 20+7 34+7 30+13 Widely recognized procedures governing implantation, as described in section 1.2, were those followed within the research projects. Great attention was paid to the design of the systems and cost allocation procedures. Furthermore, coherent issues relating to the effectiveness of implementation were considered. The findings accomplished through the case studies have been previously published in much more detail (Popesko, 2008). This paper presents the final application methodology, which have been based on performed case studies and its findings. 3. Implementation methodology - Major findings The first part of the ABC application process was to define the appropriate hierarchy of steps involved, these being: 1. A feasibility study and review (Glad and Becker, 1996) 2. Identifying the major activities and cost objects within the ABC model 3. Assigning costs to activities 4. Calculating the primary rates of individual activities 5. Calculating the costs of defined cost objects These stages were worked out whilst the case studies were being conducted. It became apparent through practical implementation that it was necessary to build upon Drury´s (2001) elementary methodology. Prior to planning the structure of the systems, an important measure was a feasibility study and review. This step is required in order to analyze the effectiveness and impact of implantation, as well as to identify all the features and characteristics of a future system. The form of ABC put in place also depends on the purpose and information desired from it. The individual stages of the implementation process are described in the following chapters. 3.1 Feasibility study and review As mentioned above, the main aim of this phase of the ABC implantation is to define the benefits it provides and the methods for utilizing the outputs of system information, as well as the costs relating to implementation and operation. The initial impulse for putting ABC in place normally comes from the management of a company. There is an expectation that one will reap dividends through improved cost management levels and the superior quality of information provided by the system. The reasons senior managers consider going ahead with implementing ABC could be discerned as the following (Popesko, 2008): 7 Popesko • A high number of expensive overhead activities; plus construction, project management, and maintenance • A relatively high portion of overhead costs • Intense competition • Invisible relations between customers’ projects and costs • An intention to reduce costs • Creating an effective tool for costing products for sellers The anticipated benefits brought about by the information outputs of an ABC system need to be very carefully analyzed along with their features. The essential problem is the difficulty of quantifying the economic benefits of ABC implementation and especially its impact on company profitability (Staněk, 2003). However, future users of the information generated could, during this phase, define the contribution of the same for their own purposes. Implementation of the system will require considerable effort and expenses and it should be questioned whether or not it will add value to the business. Information overload as well as the capability of the management team to absorb the content of the system will certainly be factors to consider in this respect. Beside the ABC benefit analysis, the cost analysis of ABC implementation has to be made within this phase of implementation. The feasibility study should look at the normal cost considerations which can be summarized as follows (Glad and Becker, 1996): • Development costs: o outside assistance; o internal staff costs; o ABC/M system costs (costs for purchasing of ABC IT system); o support system changes; • Operating costs: o capturing costs (costs of data capturing); o system running costs; o interpretation costs; 3.2 Identifying the major activities and cost objects within the ABC model; Many authors (Drury, 2001), (Glad and Becker, 1996), (Staněk, 2003) consider the definition of activities as the starting point of an ABC implementation process. As was witnessed after performing the case studies, creating a single definition for activities without the cost objects being also defined proved insufficient for successful implementation. The structure of activities can be related to the cost object structure because different data are processed and various outputs are desired of the individual cost objects. Consequently, it is necessary to split this phase of ABC implementation into two coherent sections: i.e. defining activities and defining cost objects. 8 Popesko Activity definition Activities form the basis of measurement of all relevant information in an ABC system. Therefore, it is imperative to define the activity at the right level of detail. Too much will cause information overload and too little may lead to insufficient information being available for analysis. Several procedures defining activities may be used: • Analysis of the organizational structure of an enterprise • Analysis of the workplace • Analysis of personnel costs Applying all three ensures that no activity is overlooked. Moreover, several important guidelines relating to an activity’s definition can be composed as follows: • Every defined activity should be related to a relevant cost pool; the objective of activity definition is not to conduct process analysis, but to set up the costing system • Actions and tasks performed within an activity should be precisely described to avoid any misunderstanding in later stages of application • A code number may be allotted to all individual activities for easier processing • It is suitable to define the appropriate number of activities, totaling between 20 to 30 Activities defined within the ABC system are classifiable as either primary or secondary (support) activities. Primary activities might relate to actions which the organization performs to satisfy external demands, while secondary refers to those performed to serve the needs of internal “customers” (Porter, 1985). This classification is essential for cost allocation procedures, as described in later chapters. The Porter model could prove useful as a framework for an activity structure especially suited to manufacturing industries. Porter classified the full value chain as nine interrelated primary and secondary activities. These activities are then further delineated into primary activities that add value to the product from a customer point of view, and support or secondary activities, which ensure the efficient performance of the primary activities. (Porter,1985), (Glad and Becker, 1996) Even though Porter’s model has received criticism for its tight focus on operational activities and for neglecting innovation and service processes, its foundation proves very suitable for the construction of a company costing system. (Hromková, 2004), (Popesko, 2008). The activities identified might also be collated within aggregate processes, which could relate to specific cost objects. Cost object definition Traditional costing methods normally utilize a single cost object – a product or service. However, an effective and accurate costing system has to incorporate multiple cost objects. Distinct products and services usually comprise the most frequently used cost objects. In reality though, it is possible to discern a much wider spectrum of cost objects. Using multiple cost objects makes costing systems far more complex, but this principle is an important requirement for accuracy. How can one allocate the costs of a sales department right down to product level when the inputs 9 Popesko consumed by each customer served by the department may vary widely, even if only one type of product is produced? The structures of both activities and cost objects are very closely tied. This is why defining activities and cost objects in one phase of implementation proved efficient. The close bonds between an activity and a cost object’s structure is also upheld by traditional classifications of activities, where every category of activity is related to a different cost object. The activities are classified as (Kaplan, Cooper, 1998): 1. Unit level activities, which are performed each time a unit of a product or service is produced 2. Batch level activities, which are performed each time a batch of goods is produced 3. Product sustaining activities, which are performed to enable individual products to be produced and sold 4. Customer sustaining activities, which are performed each time a customer is served in situations where the customer forms the cost object 5. Facility sustaining activities, which are performed to support a facility’s general manufacturing process; these include administrative staff, plant management, and property costs The case studies performed demonstrate the need to identify multiple cost objects as the product, project (a special type of product, produced for limited time), and customer which is also true for manufacturing industries, the reasons being: • Industries serve a number of very different customers, each of whom consumes differing quantities of customer related activities (costs) • Individual projects (products) consume differing quantities of product sustaining costs. • The various products of projects may vary in profitability, but the ultimate target is to reach an appropriate level of customer profitability. The ABC model should provide data for cost object profitability measurement 3.3 Assigning costs to activities Assigning costs to activities represents the first stage of the allocation process within the ABC system. Firstly, not all company costs will be allotted to the activities defined. Company costs could be classified according to their nature under (Drury, 2001): • Direct traceable costs – those allocated directly to a cost object using the same principles as traditional costing methods • Activity-traceable costs – those allocated to identified activities • Non-traceable costs (or unallocated costs), which could be allocated to a cost object in proportion to other costs, or may be covered by a small increase in the target margin Cost allocation to defined activities might prove very complicated in practice and eventually take up an important amount of the implementation process time. The reason is that the structure of activities and structure of a company’s department usually clash somehow. The activity cost matrix could be invaluable for assigning company costs classified in company cost centers to activities. Very often it is necessary to define a resource cost driver in order to effectively allocate such costs. 10 Popesko Resource cost drivers help to assign costs to a specific activity, when the cost in evidence is aggregated in general book entries. The following resource cost drivers were used in the case studies: • Personnel workload – for allocating personnel costs to activities • Square meters – for allocating rent, premises depreciation, heating, and indirect electricity to activities • The quantity of machines, tools, etc. • Estimation 3.4 Calculating the primary rates of individual activities Calculating the primary rates of individual activities can be conducted in four steps: 1. Setting appropriate activity cost drivers for individual activities 2. Determining the output measures of individual activities 3. Calculating the primary rates of individual activities 4. Assigning the costs of support activities to primary activities Setting appropriate activity cost drivers for individual activities Activity cost drivers (ACD) can be defined as the factors of transactions that are significant determiners of costs (Drury 1989). Activity cost drivers should generate data about which factor causes the occurrence of the individual types of overhead costs gathered within an activity. ACDs consist of three types (Drury, 2001): 1. Transaction drivers (number of transactions) 2. Duration drivers (amount of time required to perform an activity) 3. Intensity drivers (direct charge of consumed resources to activities) The ACDs defined for a manufacturer may potentially resemble the allocation bases utilized by traditional absorption costing, particularly for manufacturing activities where duration drivers are used. However, should a large portion of direct costs and those of manufacturing activity exist, the use of the ABC system solely for the purposes of quantifying costs of product cost objects might not be efficient. A highly important requirement for a defined cost driver is the ability of an enterprise to measure the driver and quantify its output measure. If the quantity of a cost driver consumed by an enterprise and individual cost object cannot be gauged, such a cost driver cannot be used for cost allocation purposes. Occasionally, a cost driver might take the form of a determiner of cost variability. This means that if a company performs a lower number of activity units, the total costs of an activity will change. In such instances, regress and correlation analysis may be used to determine an appropriate activity cost driver. Nevertheless, it is far more common for activity costs to be largely fixed in character. Under these circumstances, a cost driver is simply a gauge of cost allocation. Determining output measures of individual activities The next step in the ABC implantation process is to determine the output measures of individual activities. These represent the number of activity units consumed during a specific period. In fact, an output measure determines activity capacity and is used to work out activity unit costs. 11 Popesko The most significant provision governing activity capacity measurement is that of setting the correct activity capacity, this capacity being determined by the level of its denominator. These denominator levels are frequently applied in manufacturing operations where capacity can be technically and very precisely measured. In the case of overhead activity measurement, the setting of appropriate denominator levels could prove more complicated because overhead activities usually no have technical parameters that might easily be gauged. The capacity of overhead activities is usually measured by working out the number of output measures within a cost period. Output measures are, in the ABC system, used to determine the recovery rate of each cost pool/activity. Two alternatives exist for this purpose (Glad and Becker, 1996) actual output, which uses the actual output of a particular output measure, and maximum capacity, which sets the constant capacity level for each activity. Generally, calculating activity recovery rates based on actual output could prove easier to perform, since no maximum capacity determination is necessary. Calculations based on the maximum capacity are more accurate and provide for greater possibilities of utilization, e.g. capacity purposes. The challenge is to work out how to set the maximum capacity of overhead activities. Calculating the primary rates of individual activities Activity capacity output measures are used for quantifying activity unit costs, the rate for which is calculated as follows: (1) Activity cost per unit, also called primary rates could be then used in the ensuing stages of ABC implementation as important measurements, which could be analyzed. Assigning the costs of support activities to primary activities Following the calculation of primary rates, the next thing to do is to allocate secondary activities to primary ones. It is possible to solve all of the problems relating to secondary activity costs if the amount of secondary cost driver units can be quantified. These are consumed by individual primary activities, such as the number of employees, SAP licenses and square meters being consumed by a primary activity like ‘Quality Control’. The costs of secondary activities are then allocated to primary activities using the output measures of secondary activities, thereby calculating the secondary activity costs of primary activities. Total primary activity costs are then worked out by combining the primary activity cost (cost pool) plus secondary activity costs (costs of secondary activities allotted to a primary activity). An identical calculation can also be performed for activity unit costs, where the unit costs of an activity (combined rate) are equal to the sum of primary activity unit costs (primary rate) plus the unit costs of secondary activities consumed by a primary activity (secondary rate): 12 Popesko The difficulty lies in the fact that these secondary activities and their output measures are not solely consumed by primary activities but other secondary activities, as well as by these activities themselves (Figure 2). This problem has also been discussed by some authors (Jacob, Mashall, Smith, 1993). Figure 2: Example of mutually and self-consumed secondary activities in the cost model (Popesko 2009) Figure 2 shows how any activities mutually consume other activity outputs. If, for example, we analyze the activity entitled Human Resources Management (HRM), it is shown that this activity consumes outputs of other secondary activities as IS/IT, Finance & Accounting, amongst others. These types of activities, providing as they do additional outputs for other secondary activities, may be described as reciprocal secondary activities. Another challenge to be faced is the self-consumption of activities. The HRM activity provides services for other company departments and activities according to the number of employees. Consequently, the number of employees is chosen as the ACD for this activity. However, this activity is performed by a specific quantity of employees. According to allocation principles, this activity (HRM) should be charged by the specific costs charge, as calculated by the activity primary rate and then denoted as other activities. This type of secondary activity, which consumes its own outputs, might then be entitled a cyclical secondary activity, because mutually consumed and self-consumed activities cause a cyclical allocation of costs. Managers and accountants facing such a challenge have to find a way of performing this type of costing allocation, because the method in which service costs are allocated can significant affect product cost accuracy. The simultaneous consumption of service department outputs is a relatively well-known issue. The most common 13 Popesko means for allocating service department costs to production departments (Jacob, Mashall, Smith, 1993) are the direct, step and reciprocal methods. Allocation procedures which also include and solve the self consumption of activities could be used. Firstly, the direct method allots all service department costs directly to production departments, completely ignoring any services provided by any individual service department to another. In contrast, the step method considers some, but not all, provisions between service departments. Costs are allocated one department at a time via this method, but only to any remaining departments, i.e. those not yet allocated. Lastly, the reciprocal method explicitly recognizes all reciprocal services. It uses simultaneous equations to, firstly, reallocate service department costs among all the service departments, and then to production departments. The reciprocal method may effectively be used for service department cost allocation in ABC. Despite the not even reciprocal method analyses the self consumption of activities, could be very effective for practical use. Any more complex mathematical methods could be also used, which also incorporate the self consumption of activities. One such method was also used in the case studies we conducted (Popesko, 2009) or is described by some authors (Jacob, Mashall, Smith, 1993; Žůrek 2009). 3.5 Calculating the costs of defined cost objects The final stage of ABC calculation involves working out the costs of defined cost objects. The objective of this phase is to quantify the number of activity units consumed by individual cost objects. This calculation is performed on a bill of activities this being a description of the “journey” a product (or another cost object) makes through the various activities en route towards completion. It is of great importance to accurately work out the multiple cost drivers concerned and to construct an intelligible costing statement for different types of users. 4. Utilization of ABC information outputs Performed case studies showed that the primary benefit of application, as mentioned in theoretical sources – the higher accuracy of product costs quantification, did not really play such a vital role. The variations between the original costing and that of ABC, caused by a different allocation of overheads, were at a relatively low level, in average about 10%. On the other side, the ABC implementation in researched enterprises brought about a significant improvement in information for managers. In a further phase of the system’s utilization, a tool was constructed for preliminary calculations for price negotiation purposes. Implementation of the ABC system in manufacturing enterprises produced two major benefits: • • Firstly, a better understanding of process and activity costs, enabling managers to make decisions in order to optimize the costs of an activity. Secondly, correctly quantifying the costs of distinct production activities. As the production of individual products consists of different operations, the ABC system is able to precisely describe the manner in which a product goes through the 14 Popesko various operations, as well as accurately calculating the costs of those operations. 5. Discussion Utilization of the ABC system in companies in the manufacturing industry with similar production to that presented in our case studies brings some specifics. Despite the relatively low portion of overheads, which are allocated differently than with an absorption costing system, the variations in product and project costs may prove important so as to produce better evidence of costs of individual operations’ activities. Implementation also showed that the ABC model applied in the case studies was unnecessarily detailed for costing purposes. Most of the activities could be gathered together into several major cost pools or activities. Nevertheless, the level of detail is adequate for analyzing processes and activities. Should the ABC system only be implemented to improve the field of overhead cost allocation, the benefits of the system would be debatable. The same could be brought about by a much simpler calculation system, but the effectiveness of ABC’s principal use for allocating project management costs or those for a sales department is undeniable. The application of ABC or other more sophisticated costing systems in manufacturing industries continues to be widely discussed by academics and potential users. ABC implementations are much more common in the area of services, as well as energy companies, telecommunications, and financial institutions. Manufacturers often consider ABC a rather unsuitable tool, in addition to being very expensive and not resulting in significant benefits. One reason for this is that senior managers too often do not think of ABC as a complex system, i.e. one used not only for costing purposes, but also for many other functions. The principles defined above can be considered as guidelines applicable for manufacturing companies when implementing ABC. They are quite general in nature so might also prove useful in any situation where practical application could be highly specific and differ from another. Conclusion The Activity-Based Costing system, whose fundamental principles have been explained in this paper, is central to Activity-Based Cost Management. Information provided by this system boasts wider areas of application compared to that of traditional costing systems. Besides the more valuable quantification of costs allocated to cost objects and the detection of relations between cost consumption and operation, the existence of different types of cost objects also allows costs to be analyzed at differing levels of managerial decisions. Activity-Based Management methods have a broad range of uses, permitting the empowering utilization of ABC information for a wide variety of company functions and operations such as process analysis, strategy support and time-based accounting, monitoring wastage, as well as quality and productivity management. In addition to information outputs, which could dramatically improve the quality of the decision making process, it is also necessary to define any disadvantages of the ABC/M system. Applying this method requires higher costs and difficulties could arise 15 Popesko during its use due to the various activities that can appear. The implementation of ABC/M is a collective process and brings with it new cost calculation rules whilst presupposing a change of attitude and behavior. The results of case study we performed show an example of the system being utilized in the processing industry, a characteristic of which is a large portion of material costs. Implementation showed that despite limited impact in the field of overhead cost allocation, the benefits in the areas of process and activity analysis meant it proved a success. References Cokins, G. 1996, Activity-based cost management: Making it work: A manager’s guide to implementing and sustaining an effective ABC system, Irwin, Chicago Cokins, G. 2001, Activity-Based Cost Management: An Executive's Guide, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 047144328X Drury, C. 1989, Activity-based costing, Management accounting (UK), Sep. 1989: p. 60-63 Drury, C. 2001, Management and Cost Accounting, Fifth Edition, Thomson Learning, ISBN 1-86152-536-2 Glad, E., Becker, H. 1996, Activity-Based Costing and Management, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 0-471-96331-3 Hromková, L., 2004, Teorie průmyslových a podnikatelských systémů I., Tomas Bata University Press, ISBN 80-7318-038-3 Innes, J., Mitchell, F. 1998, Practical Guide To Activity-Based Costing, Kogan Page, ISBN 0749426209 Jacobs, F., Marshall, R., Smith, S. 1993, An alternative method for allocating service department costs, Ohio CPA Journal; Apr 1993; 52,2; ABI/INFORM Global pg.20 Kannainen, J., Varila, M., Paranko, J. 2002, The Unused Capacity Trap, Pre-Prints of the 12th, International Working Seminar on Production Economics. Innsbruck, Austria, 18-22 February, Vol. 3. pp. 229-240. Kaplan, R., Johnson, H. 1987, Relevance lost: Rise and fall of management accounting, Boston:Harvard Kaplan, R., Cooper, R. 1998, Cost & Effect – Using Integrated Cost Systems to Drive Profitability and Performance, Harvard Business School Press, ISBN978-087584-788-7 Kim, Y., Ballard, G. 2002, Case study – Overhead cost analysis, Proceedings IGLC, Gramado, Brasil Král, B. 2006, Manažerské účetnictví, Management Press, ISBN 80-7261-141-0 Lucas, M. 1997, Absorption costing for decision making, in Management Accounting, ABI/INFORM GLOBAL, pg. 42 Nekvapil, T. 2004, Netradičně o ABM – Controller a zombie, Controlling 4/2004, ISSN 1801-6251 Petřík, T. 2007, Procesní a hodnotové řízení firem a organizací, Linde Praha, ISBN 978-80-7201-648-8 Popesko, B., Novák, P. 2008, Principles of overhead cost allocation, from Issues in Global Business and Management Research - Proceedings of the 2008 International Online Conference on Business and Management (IOCBM 2008), Universal-Publishers USA, ISBN 9781599429441 16 Popesko Popesko, B. 2008, Activity-based costing applications in the plastics industry – Case study, from Issues in Global Research in Business and Economics, FIZJA International, Orlando USA, ISSN 1940-5391 Popesko, B. 2009, How to manage the costs of service departments using ActivityBased Costing, in International Review of Business Research Papers, World Business Institute, Melbourne, Australia ISSN: 1832-9543 Porter, M. 1985, Competetive advantage, New York: Free Press Potkány, M. 2008, Personnel outsourcing processes, E+M Economics and Management, Vol. 4, ISSN 1212-3609 Sebestyen, Z., Juhász, V. 2003, The impact of the costs of unused capacity on production planning of flexible manufacturing systems, Periodica Polytechnica Ser. Soc. Man. Sci. Vol.11, No.2, PP 185-200, ISSN 1587-380 Staněk, V. 2003, Zvyšování efektivnosti procesním řízením nákladů, Grada Publishing, ISBN 80-247-0456-0 Žůrek, M. 2009, Activity-Based Management - Competitive market inside the organization, Dissertation thesis, Tomas Bata University Press 17