Living on the edge: Parallels between the Deaf and gay

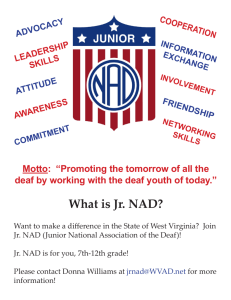

advertisement