Title – Heading Level 1

advertisement

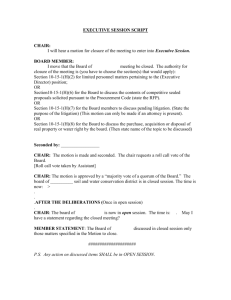

Company Meetings – Tips and Insights: The Role of the Chair Date : 12 March 2015 Author/s : David Ferguson, Chuanchan Ma In this article we look at the essential role that the chair 1 plays in the context of company meetings and the legal principles that apply to that role. Introduction The constitutions of most companies divide the corporate powers between the board of directors, which is usually given the power to manage the company’s business, and the members, who usually have the power to appoint and remove directors and change the constitution. The powers of the board and members are usually exercised through resolutions passed at a meeting. This article considers the role of the chair in the context of meetings as well as the broad corporate governance role allocated to an individual director appointed to the role of chair of a public company. This reveals the increased expectations of the role while noting the limited formal powers of the chair. The chair’s role in meetings Courts have taken the view that, generally, a meeting can only take place with more than one participant.2 This reflects the fact that “according to the ordinary usage of the English language” that it is not possible for a person to have a meeting with themselves. This is the case even though the one person present holds proxies for others.3 While exceptions to this general position have been identified to enable a meeting of a single holder of a class of shares4 , the general concept of a meeting contemplates discussion between the participants and, for this reason, courts have also held that a meeting of directors or shareholders cannot proceed without a chair. This indispensable element of any meeting was recognized in Colorado Constructions Pty Ltd v Platus5 where Street J identified that the chair’s role included the setting of the order of business, nomination of the person entitled to speak, putting questions to the meeting, declaring resolutions carried or not carried and declaring the meeting closed. As noted in a subsequent case, “the essence of chairmanship is actually exercising procedural control over the meeting”.6 In carrying out this role, the chair is required to act impartially to ensure that the meeting operates in a fair manner. As observed by Young J in NAB v Market Holdings Pty Ltd (in liq)7, citing National Dwelling Society v Sykes8: 1418644_1 It is the duty of the chairman, and his functions, to preserve order, and to take care that the proceedings are conducted in a proper manner, that the sense of the meeting is properly ascertained with regard to any question which is properly before the meeting. The chair’s role in corporate governance Most public company constitutions provide that the board of directors will elect one of their number to act as chair and that the person elected also acts as chair of general meetings. While the position of chair could be filled on an ad hoc basis, there is a broader corporate governance significance to the role that the chair of a public company plays. This is reflected in the following excerpt from commentary to Recommendation 2.5 of the ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations: The chair of the board is responsible for leading the board, facilitating the effective contribution of all directors and promoting constructive and respectful relations between directors and between the board and management. The chair is also responsible for setting the board’s agenda and ensuring that adequate time is available for discussion of all agenda items, in particular strategic issues. Accordingly, the role of chair in a public company is usually attributed special status and additional remuneration. Although the position can be carried out in different individual styles, the chair often acts as spokesperson for the company on high level matters and usually plays an important link between the board and management of the company. It is worth noting that the ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations also express the view that the chair should be a non-executive role so as to separate the chair’s role from that of the chief executive officer and the executive management team. This article has been formulated on the assumption that the chair is a nonexecutive director, but a fuller discussion of this issue is beyond its scope. The allocation of a broader corporate governance role has been recognised as potentially giving rise to a more extensive duty of care and diligence on the part of the chair. As noted by Austin J in reflecting on the duties of the chair of the board of One.Tel Limited:9 1 The court’s role, in determining liability of a defendant for his conduct as company chairman, is to articulate and apply a standard of care that reflects contemporary community expectations. Austin J further noted that it is now commonplace to observe that the standard of care expected of company directors, both by the common law (including equity) and under statutory provisions, has been raised over the last century or so, and that “[o]ne might correspondingly expect that the standard for company chairmen has also been raised”.10 The individual requirements of the standard of care owed by the chair of a public company will depend on the allocation of corporate governance roles and responsibilities within the company and the skills and experience of the individual person carrying out the role of chair.11 In this respect, the responsibilities of the chair are not limited to delegated tasks but include the responsibilities with which the chair is entrusted by reason of his or her expertise and experience.12 has a duty to maintain impartiality, a casting vote should be used to maintain the status quo so as to allow further discussion of the relevant matter, it is doubtful that this general proposition exists.17 A number of provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) also recognize the special status of the chair’s role in meetings. For example, the Corporations Act acknowledges that the chair often receives multiple proxy appointments and therefore imposes an obligation on the chair to vote as proxy on a poll.18 It also gives greater scope for the chair, as compared to other directors, to vote proxies in connection with directors’ remuneration.19 David Ferguson, Partner Telephone +61 2 8915 1o53 Email david.ferguson@addisonslawyers.com.au The authority of the chair Despite the essential nature of the chair’s role in the context of meetings and the elevated duty of care and diligence that may be attributed to the chair’s role within public companies, a person appointed to that role does not have authority, merely by virtue of that office, to make decisions binding on the company or to give binding directions.13 The board makes its decisions by resolutions which are carried or lost depending on a majority vote. Accordingly, unless the board has delegated powers, the chair has no more power to carry out matters on behalf of a company than any other individual non-executive director. The chair’s authority in the context of meetings is more robust. Constitutions typically provide that the chair is elected by the board of directors and, in some cases, provide that the chair has a casting vote at meetings of directors and members. Consistent with his or her role in regulating meetings, constitutions also usually provide that the chair of a general meeting can require a vote to be taken by way of a poll and empower the chair to make certain rulings at the meeting.14 Where a company’s constitution provides that rulings by the chair on certain matters are final and the chair makes a ruling on those matters in good faith, there is no right in the meeting to challenge the ruling, although it could be overturned by a court in appropriate circumstances. Even if a decision is made by the chair in connection with the proper conduct of a meeting that does not have the protection of an express constitutional provision, courts have indicated that the decision should be regarded as correct unless the contrary is proved by a person objecting to it.15 If the chair has a casting vote at a meeting, that right must be exercised “honestly and in accordance with what (the chair) believes to be the best interests of those who may be affected by the vote”. Subject to this, the chair is entitled to exercise the casting vote as he or she thinks fit.16 While there has been a view that, because the chair 1418644_1 Chuanchan Ma, Solicitor Telephone +61 2 8915 1o03 Email Chuanchan.ma@addisonslawyers.com.au © ADDISONS. No part of this document may in any form or by any means be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written consent. This document is for general information only and cannot be relied upon as legal advice. 1 We have adopted the term “chair”, rather than chairman or chairperson. Sharp v Dawes [1876] 2 QB 26. Re Sanitary Carbon Co [1877] WN 223. 4 Re Hastings Deering Pty Ltd (1985) 9 ACLR 755. It should also be noted that in the case of a single-member company, section 249B of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Act) provides that a resolution may be passed without a meeting by the member recording it and signing the record. However, as explained by Barrett J in CIC Insurance (prov liq apptd) v Hannan & Co Pty Ltd (2001) 38 ACSR 245;246, this provision may not be able to be used where the Act itself imposes some special requirement relating to a meeting, which indicates that an actual meeting is required. For example, section 203D(4)(b) which gives a director of a public company to whom a resolution for removal is directed a right to speak to the resolution at the meeting. Barrett J observed that in cases of this kind, it may be that an actual meeting is required as a necessary part of the statutory machinery so that, in the case of a company having one single member, not only can section 249B not be used, but the normal meaning of “meeting” as a plurality of persons is displaced and the legislature countenances a meeting of one. 5 [1966] 2 NSWLR 598 at 600. 6 Woonda Nominees Pty Ltd v Chng (2000) 34 ACSR 558 at [35] per Owen J. 2 3 7 8 (2001) 37 ACSR 629 at [88]. [1894] 3 Ch 159 at 162 ASIC v Rich and Ors (2003) 44 ACSR 341 at [71]. It should be noted that this case involved preliminary proceedings in which the chair of One.Tel, Mr Greaves, sought to strike out proceedings by ASIC against him, on the basis that the extra duties that ASIC contended he was subject to were not known at law. Austin J dismissed the application and found that a reasonable cause of action had been disclosed against Mr Greaves, on the basis that a chair may have a higher duty of care and due diligence arising from the chair’s responsibilities. However, ASIC and Mr Greaves had reached a settlement before the final proceedings. 9 10 2 11 ASIC v Rich at [49]: see also Shafron v ASIC (2012) 247 CLR 465 for similar discussions in relation to a person holding the office of company secretary and general counsel. 12 ASIC v Rich at [50]. 13 Galipienzo v Solution 6 Holdings Ltd (1998) 28 ACSR 139 at 149. 14 See replaceable rules in sections 250G(b) (“Objections to right to vote”), 250J(2) (“Show of hands conclusive”), 250L(1)(c) (“When a poll is effectively demanded”) and 250M(1) (“Where poll may be demanded”) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). 15 In re Indian Zoedone Company [1884] 26 Ch 70; Corpique (No 20) Pty Ltd v Eastcourt Ltd (1989) 15 ACLR 586. 16 R v Bradford Metropolitan City Council; Ex parte Corris [1989] 3 All ER 150 at 160. 17 Cresvale Far East v Cresvale Securities (2001) 19 ACLC 659 at 677. 18 Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), section 250BB(1)(c). 19 Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), sections 250BD(2) and 250R(5)(b). 1418644_1 3