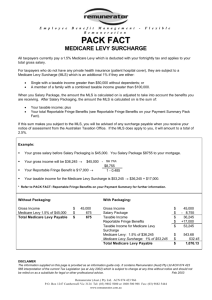

Increase of the Income Tax Thresholds for the Medicare levy

advertisement