Workers' Rights on ICE: How Immigration Reform Can Stop

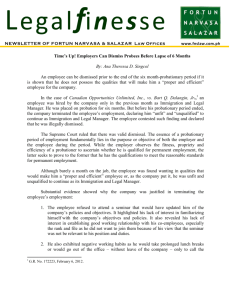

advertisement