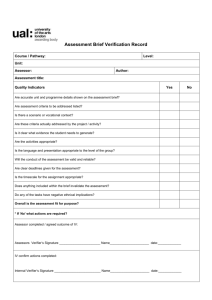

SC522 - BC Assessment

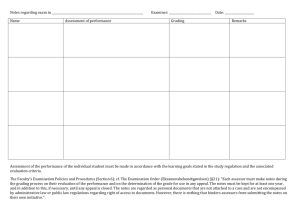

advertisement