ARTICLE IN PRESS

Tourism Management 28 (2007) 519–529

www.elsevier.com/locate/tourman

Reaearch article

Selective interpretation and eclectic human heritage in Lithuania

A. Craig Wight, J. John Lennon

Moffat Centre for Travel and Tourism Business Development, Glasgow Caledonian University, Cowcaddens Road, Glasgow, Scotland G4 0BA, UK

Received 31 October 2005; accepted 10 March 2006

Abstract

This paper examines recent controversy in Lithuania surrounding 20th century wartime tragedy with particular emphasis on

contrasting the commemoration of the mass extermination of the Jewish community and the suffering of Lithuanian Partisans during

Soviet Occupation. Comments are made on the consequences of authorities eschewing research into these areas and the consequent

implications for the modern human and tourism heritage offering that currently exists within the country. The paper postulates through

analyses of two case studies that recent tragedy in Lithuania is a newly fashioned ‘taboo’ for authorities and locals. Analysis suggests that

there are dichotomous representations of tragedy inherent in two of Lithuania’s high profile ‘dark’ tourist attractions. The paper builds

on previous literature examining the phenomenon of ‘dark tourism’. The conclusion postulates the need for an open and transparent

historical perspective on interpretation and education. These are primary considerations in promoting collective future acceptance of the

country’s past.

r 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Lithuania; Vilnius; Dark tourism; Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum; KGB Museum of Genocide Victims; Selective interpretation

1. Introduction

The term dark tourism was coined by Lennon and Foley

(2000) to describe the attraction of visitors to tourism sites

associated with recent and historic incidences of death and

disaster. These sites have been classified in literature

(Lennon & Foley, 2000; Smith, 1998) into ‘primary’ sites,

such as holocaust camps to sites of celebrity deaths, and

‘secondary sites’ sites commemorating tragedy and death.

It is the second category, (specifically museums associated

with tragedy and death in the Lithuanian context) that will

be examined in this paper.

Some authors who have broached the subject of dark

tourism have explored the reticence of destinations and

cultural groups to confront ‘dissonant’ or inharmonious

heritage (see for example, Dwork & Van Pelt, 1997;

Tunbridge & Ashworth, 1996). Hypotheses have been put

forward on the authenticity of the past and the visitor

experience at ‘dark’ heritage sites. Debate continues on the

management and manipulation of cultural landscapes to

Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 141 331 8400; fax: +44 141 331 8411.

E-mail address: cwi2@gcal.ac.uk (A. Craig Wight).

0261-5177/$ - see front matter r 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2006.03.006

accommodate tourism activity, with reference to sites

presenting death, war and tragedy inter alia to the visiting

public (for example, Beech, 2000; Wight & Lennon, 2004).

Such contention has lead to deliberation over issues such as

the management of ‘dark’ sites, interpretation of these sites

and the motivation of the visiting public (Lennon & Foley,

2000; Smith, 1998; Strange & Kempa, 2003).

The context has widened to include academic enquiry

into visitation to sites associated with the ‘dark’ side of

human nature including prisons (Strange & Kempa, 2003)

and labour camps associated with World War II. The

notion is not an entirely western one, indeed some research

has been conducted into dark heritage in non-western

countries, for example Vietnam and Cambodia (Henderson, 2000), Japan (Siegenthaler, 2002), Africa and the US

(Shackley, 2001; Strange & Kempa, 2003). This paper

extends the academic coverage of the phenomenon in the

Lithuanian context and it confirms Lithuania as a

destination with a dark heritage of invasion, genocide

and repression. It is the representation of this dark past

that forms the basis for examining two museums with

varying approaches to the representation of tragedy. The

case studies in this paper seek to present issues such as

ARTICLE IN PRESS

520

A. Craig Wight, J. John Lennon / Tourism Management 28 (2007) 519–529

management dilemmas, visitor interpretation, authenticity

and informational accuracy. The issue of ‘selective’

interpretation is examined in the context of the representation of the country’s dark past in two key museums in

Vilnius.

2. Background to Lithuania and Vilnius

The Republic of Lithuania is located in Eastern Europe

on the coast of the Baltic Sea with a population of

approximately 3.5 million (Clottey & Lennon, 2003).

Vilnius, the capital has a population of 542,287 (Vilnius

City Municipality, 2005). The Old Town of Vilnius is the

historical centre and is one of the largest in Eastern

Europe. Vilnius also represents the largest administrative centre in Lithuania comprising all major political,

economic, social and cultural centres

Lithuania gained independence (by decree of the

erstwhile German Tsar) in 1918, yet the threads of

independence began to weaken by 1939 when fascist

Germany annexed Klaipeda and the surrounding region

(Laučka, 1986). In July 1940, the country was largely

annexed by the USSR and the successive German

occupation in the years to follow eradicated the majority

(over 200,000 lives) of Lithuania’s Jewish population

(Bousfield, 2004; Lopata, 1993).

Following the devastation wreaked by World War II the

nation found itself on the brink of physical annihilation.

The period following the war saw Soviet domination of the

nation and its economy, with independence coming in 1991

following a long and bloody period of resistance.

3. Tourism in Lithuania

Prior to independence from the Russian Federation in

1991, tourism in Lithuania followed traditional patterns of

centrally planned leisure activity. During this period

Lithuania was part of the larger, centrally planned Soviet

economy which revolved around 5-year state plans.

Patterns of tourism in centrally planned economies have

been well documented (Hall, 1991; Shaw, 1979). A strong

emphasis was placed on spa and sanatorium based leisure

which Lithuania was naturally positioned to benefit from,

and subsequent resort development of spa facilities at

Birstonas and Druskininkai occurred. Other planned

activities included state organised group tours and excursions focussed around the capital, Vilnius, and the Baltic

Sea resorts at Palanga and Klaipeda.

Lithuanian hotel and sanatoria stock which were

developed by the state in the period 1950–1975 and have

seen deterioration and dating of facilities following

independence. However, many of these facilities remain

in use although levels of service, quality and maintenance

are all problematic.

After independence in 1991 the most significant growth

has been in tourism visits to the capital, Vilnius, and this

follows a development pattern for such emergent destina-

tions which sees tourism development concentrated in this

way (Lennon, 1996). These cities provide ideal short break

destinations for leisure tourists and their government and

administrative functions serve to catalyse business tourism.

Consequently, like Estonia and Latvia to the north,

Lithuania is progressing with capital city bias in tourism

development. Meanwhile, other parts of the country are

struggling to preserve identity and maintain even domestic

levels of visitation. Many of the problems discussed by

Jaakson (1996) in the context of Estonia in relation to

overdevelopment of the capital and its heritage areas have

clear parallels to Vilnius.

3.1. Tourism growth and the stabilisation of the Lithuanian

economy

The growth in tourism in Lithuania has followed the

economic reforms undertaken since independence and the

transition towards market economy. Lithuania inherited

the complicated legacy of over 50 years of Central Soviet

planning and in 1991, upon independence the Russian

Federation introduced massive increases to the prices of

energy and raw materials exported to Lithuania the result

was hyper-inflation, downturns in living standards and a

decline in industrial output. A programme of economic

stabilisation, privatisation and free market reform helped

create a supportive environment for the introduction of

monetary policy and the reintroduction of the Lita which

was pegged to the Euro in 2002. Privatisation has resulted

in the transfer of state assets to the private sector via

voucher schemes and cash sales. In addition, agricultural

land is now 40–50% privately owned although significant

hardship remains in this sector (Baltic Database, 2002).

Tourism constitutes one of the fastest developing growth

areas of the economy. There are currently over 600 firms

involved in tourism contributing some 5–6% of Lithuanian

GDP (Lithuanian National Tourism Statistics, 2004). The

benefits of EU membership have done much to raise the

profile of the Baltic States. Lithuania is likely to see major

development of the capital, with slower development in the

rural and coastal municipalities.

This paper will examine the emergent destination of

Vilnius and how this new and relatively dynamic city

economy is dealing with its past. The visitor attractions

of the capital underlie and reaffirm the country’s history

from the magnificence of the baroque old town, to the

remains of the Jewish ghetto.

4. Methodology of Museum analysis–the context of Vilnius

The following sections present explanatory case studies

of two museums which can be considered ‘dark attractions’. Each is concerned with providing access to

collections that can be fundamentally identified as ‘dark’.

Managing such sites of human atrocity can be contentious,

particularly when the atrocity is recent and management

decisions must be made whilst the survivors and relatives of

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Craig Wight, J. John Lennon / Tourism Management 28 (2007) 519–529

the victims are still coming to terms with the event. The

Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum is juxtaposed alongside

the Genocide Museum to expose differing approaches to

managing the commemoration of Lithuanian tragedy.

Analyses of such approaches to managing ‘dark’ pasts

have been commodiously concerned with ‘mega’ dark

attractions such as Auschwitz (Beech, 2000) and The

Holocaust Museum in Washington (in the context of land

mark cultural museums) by Lennon and Foley (2000).

Thus, the cultural and management contexts of these

Lithuanian dark sites are examined to identify the extent to

which public perceptions of the issues addressed in the

museums are crucial considerations for managers.

Explanatory case study design has been selected with

cognisance of Yin’s (1994) categories of data collection (see

below). Crucial to the content of the case studies is the

presentation and analysis of publications available from

each museum which offer opposing views and accounts of

events associated with the Holocaust. Of further importance are the interviews which were conducted with senior

staff from each museum which provide some comprehension of management approaches adopted in each museum.

Six important types of data can be collected in order to

present a robust case study. Yin (1994) classified these as

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Documents

Archived records

Interviews

Direct observation

Participant observation, and

Artefacts

The multi-modal approach for the two case studies

presented in this paper considers the first, second, third,

and sixth of these categories. As far as possible, an

objective approach has been adopted with cognisance of

the need to present conclusions based on factual evidence

from sources including museum promotional literature,

interviews with senior staff and experience from visitation.

Like most research, qualitative document analysis is

interpretive and can allow for instances of certain meanings

and identification of emphases which can be used for

demonstration. Altheide (2000, p. 291) lists six steps to

follow in order to carry out systematic analysis:

(1) Pursue a specific problem to be investigated.

(2) Become familiar with the process and context of the

information source.

(3) Become familiar with examples of relevant documents,

noting the format in particular. Select a unit of analysis,

for example, each article.

(4) List several items or categories to guide data collection

and draught a protocol (data collection sheet).

(5) Test the protocol by collecting data from several

documents.

(6) Revise the protocol and select several additional cases

to further refine the protocol.

521

These steps were proximately adhered to in the case

studies to follow. For example, a number of English guide

books and museum publications were analysed (some

revealing conspicuously contrasting accounts of the past)

satisfying points 3 and 6 of Altheide’s recommendations.

Additionally, to facilitate analysis and to simplify reference

the authors produced summary tables which are based on

interviews and documentary analyses and their emerging

meta-typologies. As Zonabend (1992) points out, explanatory case studies should incorporate the views of the

‘actors’ in the case under study. These tables are based on

the views of key management figures from each museum

and they conclude each case study section, summarising

themes and the ways in which these themes are manifest in

each museum environment.

The two museums, the Vilna Gaon Lithuanian State

Jewish Museum and the Museum of Genocide Victims are

relevant within the evolving paradigm of ‘dark’ attractions

which have so far been categorised as western tourist

attractions associated with, and addressing issues of war,

death and disaster. The methodology selected includes

textual analysis of books, photographs and illustrations

and E-mail correspondence (in the case of the Vilna Gaon

Lithuanian State Jewish Museum), in addition to written

text in the form of publications and news letters purchased

or obtained from each museum. Interviews were also

conducted with senior figures from each site. The Academic

Secretary of the Vilna Gaon Lithuanian State Jewish

Museum agreed to an interview, as did the director of the

KGB Museum of Genocide Victims.

In terms of methodological limitations, language has

presented as the greatest barrier to penetrating Lithuanian

societal discourse surrounding the role of the two

museums, and the historical events they represent. Interviews, guide books and other written and spoken records

have been interrogated in English and the caveat must

therefore be that there has been be no analysis of the

discursive formations surrounding both museums.

5. The centrality of dark tourism and methodological

concepts

Academic commentary and interest in dark tourism may

have its origins in the work of Tunbridge and Ashworth

(1996), Dwork and Van Pelt (1997) and Lennon and Foley

(2000). These authors (and subsequent contributors) have

researched the reluctance of destinations and cultural

groups to confront dissonant or inharmonious heritage

(Wight, 2006) and they have contextualised and defined the

importance of authenticity and visitor experiences at ‘dark’

heritage sites. The management and manipulation of

cultural landscapes towards accommodating tourism interest has been a persistent topic in related academia.

Contention has lead to debate over contemporary management issues related to the presentation of ‘dark’ sites using

various interpretative techniques.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

522

A. Craig Wight, J. John Lennon / Tourism Management 28 (2007) 519–529

Previous work (Wight & Lennon, 2004) has outlined the

centrality of interpretation in the context of museums

concerned with the commemoration of ‘dark’ history. The

methodology adopted in Wight and Lennon (2004)

combined questionnaire design with covert participant

observation. Other methods that have been tested in

academic enquiry into dark tourism have been predominantly qualitative (Wight, 2006). These have included

semiotic and discourse analyses (Siegenthaler, 2002), semistructured interviews and overt observation (Lennon &

Foley, 2000) and ethnography (Smith, 1998). The methods

have been applied to large units of analysis (for example, in

the case of Smith’s ethnography) and to individual tourism

operations of ‘dark’ interest (for example, Beech, 2000).

This methodology seeks to combine interviews, observation and qualitative document analysis in the case study

context. These exploratory (grounded) case studies analyse

management issues and widen the meta-analysis of dark

tourism to include the Baltic States, a region rich in

dissonant heritage.

(2001, p. 1) calls for clarification and further exploration of

this complex past in arguing that:

This is a difficult and painful theme from what seems to

be a distant past. But history is such that problems do

not vanish nor disappear with time, and the need to

record past events becomes even more urgent as the

number of participants and witnesses decreases. Sooner

or later the truth has to be faced and events must take

their rightful place in the historical process.

7. Case study 1—the Vilna Gaon Lithuanian State Jewish

Museum

7.1. Location and background

The main branch of the Vilna Gaon State Jewish

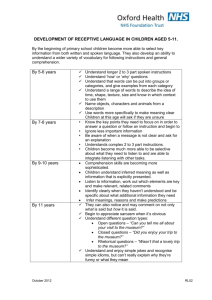

Museum (henceforth, VGM) is near the centre of Vilnius

on 12 Pamenkalnio Street (presented as Fig. 1). This is the

‘Holocaust Museum’ and is situated off the main

thoroughfare with limited signage (there is only one sign

visible from the street).

The museum houses exhibitions in four other locations:

6. Interpretation in the commemorative environment

Interpretation is the primary means by which museums

communicate with visitors and it is through interpretation

that memory and audience engagement becomes selective

and syncretic. As Ham and Krumpe (1996, p. 2) argue:

Interpretation, by necessity, is tailored to a noncaptive

audience—that is, an audience that freely chooses to

attend or ignore communication content without fear of

punishment, or forfeiture of rewardy Audiences of

interpretative programmes y freely choose whether to

attend and are free to decide not only how long they will

pay attention to communication content but also their

level of involvement with it.

Interactivity and innovative exhibitory techniques are

central to the entertainment experience within the museum

environment and can bring the visitor closer to the

‘experience’, however spurious the authenticity of this

experience may be. Interpretation in this sense is the sum

and substance of commemoration and can have various

impacts on audiences, often based on the political or

cultural agendas of host destinations and managers. As

Hollinshead (1999) argues, tourism is a means of production whereby the themes and sites viewed are cleverly

constructed narratives of past events which can manipulate

tourists to become involved in configurations of political

power.

The following exploratory case studies introduce evidence of such conflicting political and cultural agendas in

the context of Vilnius, Lithuania. The management of

interpretation and memorial is analysed with implications

for future collective acceptance of the eclectic ‘dark’ past

projected through the museum environment. Atamukas

The Jewish Community Centre at Pylimo Street

comprising various exposition halls.

The Paneriai Holocaust Memorial which opened in 1960

to commemorate victims of mass killings during the

Second World War. It is located on the actual site of the

killings.

The Tolerance Centre at Naugarduko Street.

The Jacques Lipchitz Gallery in Druskininkai.

The Jewish Museum, as an institution caring for Jewish

culture and traditions has featured significantly in 20th

century Lithuanian heritage. The first Jewish Museum was

founded in 1913 (Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum

(VGM), 2005), and was the result of the efforts of the

Society of Lovers of Jewish Antiquity. These activities

Fig. 1. The Holocaust Museum exhibition, or ‘Green House’.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Craig Wight, J. John Lennon / Tourism Management 28 (2007) 519–529

along with the development of the museum were abruptly

halted by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The

Jewish Museum was re-established in 1920 and on the eve

of the Second World War the museum housed over 3000

objects and some 6000 books as well as numerous artefacts,

letters, memoirs, photographs and newspaper issues

(VGM, 2005).

When Lithuania was annexed by the Soviet Union in

1940, the VGM was put under the control of the Peoples

Commissariat (Ministry) of Education and lost its independent status before being handed over to Soviet

Lithuania’s Academy of Science (VGM, 2005). A great

number of Jewish institutions were liquidated around this

time and Jewish communities, along with the Hebrew

language ceased to exist with staff and leaders from many

Jewish institutions being either arrested, or dismissed

(VGM, 2005).

7.2. The Holocaust exhibition

The Holocaust Museum (or ‘Green House’) introduces

visitors to Jewish history and houses a collection of

documents containing details of the Holocaust in Lithuania, amongst these are documents from commanders in the

‘Einsatzgruppen’ reporting on the results of their activities.

As well as documentation, the museum holds permanent

exhibitions on the Holocaust, long forgotten posters of the

Ghetto Theatre, numerous models and photographs of the

Great Synagogue, Purim dolls and other historical

memorabilia (VGM, 2005). There is also a section of the

museum honouring ethnic Lithuanians who rescued and

hid Jews from their German captors during the time of the

Holocaust.

Some members of staff in this building are either first or

second generation survivors of the Nazi Holocaust, or are

directly descended from survivors. Their collective research

has resulted in numerous publications, including a listing of

Vilnius Ghetto prisoners, a guide to the Jewish community

in Vilnius restorations of historical memory and the

assembling of a Judaic library. The museum is featured

on the Jewish Art Network, an international Internet art

gallery which assists the VGM in terms of heightened

coverage of their robust collection of Jewish art work

(VGM, 2005).

7.3. Visitation

The VGM (at the time of writing) has begun to collect

data on visitors, and reportage of this data is published in

the museum’s periodical news letter. An Excerpt from the

December 2004 edition is shown in Fig. 2.

These figures are based on the results of data collection

undertaken by staff at the three branches of the museum:

The Holocaust Museum, the exhibitions at the Pylimo

Street address and the Ponar branch comprising Paneriai

Memorial. Visitors to the Tolerance Centre are not

included since this was closed during most of 2003

523

Fig. 2. Visitors categorised by origin (source: VGM, 2004).

(VGM, 2004). Total visitor figures for 2003 based on data

collection at the three main sites total 12,500 from some 44

different countries. The museum estimates (VGM, 2004)

that they are commonly visited by historians, politicians,

public figures, students and Lithuanian school pupils and

many who seek information on genealogy or specific,

personal information. A clear peak season is identifiable as

late July through August with visitation dipping significantly during the months of December and January.

Various Lithuanian schools, colleges and other social

institutions who had been invited to the museum to learn

about the Holocaust and contemporary Jewish culture had

replied declining such invitations. It is over-speculative to

form any conclusion on the basis of these observations, yet

it is worthy of consideration given the superficial level of

visitation by ethnic Lithuanians to the museum. Other

factors to consider are the lack of signage, the lack of

marketing campaigns and the elusiveness of the museum’s

branches (there are in fact five, yet these are not

consistently advertised in tourist informational sources).

7.4. Interpretation and the presentation of tragedy

The museum has existed (in its present state and

location) for 14 years and exhibitions and artefacts are

reflective of stagnant and dated techniques. Narrative is

predominantly in Lithuanian with limited English translation. Signage and artefacts are preserved in casing or

behind protective covers and there is no use of interactive

technology.

One of the primary targets for upgrading is the

‘Catastrophe’ (Holocaust) Exhibition yet this work is

progressing slowly due to a lack of funding (VGM,

2003). The majority of the exhibits within the Holocaust

Museum are photos, documents, art and sculpture which

combine to:

yreveal the terror of the Holocaust, life in the Ghettos

and (to reflect upon) armed and spiritual Jewish

resistance in Lithuania (VGM, 2004).

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Craig Wight, J. John Lennon / Tourism Management 28 (2007) 519–529

524

Some improvements to the interpretation of the former

Jewish Ghetto in Vilnius have been developed in 2005

including narrative and signage surrounding key buildings

and historical landmarks in the area.

The museum’s academic secretary asserts that the aim of

the museum is to develop historical consciousness of

Lithuanian society, distorted under Soviet Rule. As an

excerpt from a VGM promotional leaflet notes:

The absence of knowledge about history, culture and

annihilation of Lithuania’s once largest minority, the

Jewish people, has resulted in misleading stereotypes

(VGM, 2004).

Through the analysis of museum literature and interviews with the Academic Secretariat, it can be concluded

that the museum management perceive their role as the

primary centre of historical expertise on Jewish life and its

revival in Lithuania. They also attach value to education,

access to collections and organising awareness activities

based on Jewish life in Lithuania.

7.5. Summary

Table 1 provides a summary of interpretation through

the representation of various themes which the museum

tackles. The themes presented were identified by the

academic secretary as key elements that the museum

Table 1

Representation of themes by the Vilna Gaon Lithuanian State Jewish

Museum

Theme

Representation

Holocaust/human suffering

Permanent exhibitions of

Artefacts including bones of victims

Photographs (including themes, such as

children and the Holocaust)

Documentation (of Nazis and of Jewish

victims)

Paneriai Memorial (the site of mass

executions of Jews on the outskirts of

Vilnius

A celebration of Jewish

culture and heritage

Travelling exhibitions

Artwork, including the Jewish Art

Network Internet galleries

Conferences

Education for schools/other institutions

and the wider public

Jewish culture and the

future

Publications

Seminars

Education

‘Living History’

Walking tours

Paneriai Memorial

Artwork

tackles as an institution. The representation of these

themes is grounded in observations made during visitation.

The interpretation within the museum assumes a knowledge of the crimes committed against Lithuanian Jews in

the vicinity and outskirts of Vilnius, and the chronological

sequence in which they took place. However the balance of

interpretation is clearly different to that found in the KGB

museum as noted in the second case study. The Holocaust

is presented as a Jewish tragedy as opposed to a Lithuanian

one and much of the interpretation points to Lithuanian

Nazi collaborators including policemen, doctors and other

professionals. It is this ‘real’ interpretive setting that the

manager believes may repel indigenous Lithuanian visitors,

who may prefer to avoid any level of engagement with the

issues presented.

The most interesting observation from Fig. 2 (visitation)

is that Lithuanian ethnic visitors to the museum are less

represented than visitors from other European countries. It

has been argued and reviewed earlier in this paper (Puisyte,

1997) that collaboration between German Nazis and ethnic

Lithuanians during the war occurred frequently, yet

politicians, and other authoritative stakeholders are only

now beginning to broach this subject with trepidation. The

museum representative interviewed during this study

suggested that there may be some sense of collective guilt

and apathy amongst locals surrounding engagement with

the umbrageous issue of the Holocaust. Indeed, at one

stage in the interview it was commented that local people

who had spoken on the subject of (non) visitation had

intimated that they felt it may be ‘inappropriate’ to visit

such a museum.

8. Case study 2—the Museum of Genocide Victims (KGB)

8.1. Location and background

The building is positioned on the outskirts of the Old

Town of Vilnius overlooking the former Lukiskiu Aikste,

or ‘Lenin Square’. A statue of Lenin once stood in the

centre of this square pointing towards the museum, its

main purpose being to serve as a palpable warning of the

fate that awaited those who opposed the Soviet regime. The

statue was ceremoniously removed in 1991 after a failed

coup which precipitated the final break up of the Soviet

Union and can now be found in Grutas Park (Bousfield,

2004).

The square on which the Museum of Genocide Victims

(henceforth MGV) is situated has played a long and

infamous role in the history of Vilnius and is a particularly

relevant location for a museum themed on Soviet occupation. After the 1863–64 local uprising against the Russians,

a number of rebels were publicly hanged in the square and

it was later the site of a number of atrocities committed by

Soviets on Lithuanian nationals.

The MGV building was initially built to serve as the city

court house (Bousfield, 2004) and during the first Soviet

occupation of Lithuania in 1940 it was taken over by the

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Craig Wight, J. John Lennon / Tourism Management 28 (2007) 519–529

8.2. Visitation

Statistics on visitors were not available at the time of

visitation, however subsequent E-mail correspondence with

a senior specialist of the museum provided some basic

figures. These are presented as Figs. 3 and 4 which outline

visitation statistics and visitor profiles from 2003 and 2004,

respectively.

In 2003 the museum received 12,248 visitors and of these

5787 (47%) were part of a group. Of the groups, 2940 (or

50%) were schoolchildren representing half of all group

visitors. The year 2004 saw an increase of 12% with visitor

numbers totalling 13,864. Of these, 42% were part of an

organised group, and 41% of group visits were schoolchildren touring as part of a group. In 2004 staff conducted

351 tours of the museum, and of these tours, 169 were for

schoolchildren.

Visitation to the Museum of Genocide Victims 2003

53

Percentage

52

51

Visits made as

part of a group

Visits made alone

Visits made as part of a

group

50

49

48

Visits made

alone

47

46

Visitor type

Fig. 3. Visitation to the Museum of Genocide Victims in 2003 broken

down into group and individual visits.

Visitation to the Museum of Genocide Victims 2004

70

Visits made as

part of a group

Visits made alone

60

Percentage

NKVD (the former name for the KGB). The following

year the building became a Gestapo headquarters during

the German occupation and more recently (from 1944) it

played host to incarcerated political prisoners who were

held and subjected to various physical and psychological

torture techniques in the basement (Bousfield, 2004). The

building remained as a KGB headquarters until 1991

(shortly after independence).

The MGV as it exists now was established by order of

the Minister of Culture and Education and the President of

the Union of Political and Deportees in October 1992.

Later, in 1997, the museum was renovated and in March of

the same year the Government handed all rights to the

museum over to the Genocide and Resistance Research

Centre of Lithuania with whom ownership has remained

ever since. The museum houses a collection of artefacts,

documents and photographs themed on repression against

Lithuanians by the occupying Soviet regime between 1940

and 1990 (MGV, 2004). Material on display is related to

anti-Soviet and anti-Nazi resistance, information on

partisans struggling for freedom and victims of what the

museum refers to as genocide.

525

50

Visits made as part of a group

Visits made

alone

40

30

20

10

0

Visitor Type

Fig. 4. Visitation to the Museum of Genocide Victims in 2004 broken

down into group and individual visits.

8.3. The main exhibition

One of the most notable features of the MGV is the

exterior brickwork of the building upon which are etched

the names of various victims of KGB interrogation and

murder. However, this feature does not overshadow the

strikingly controversial selection of provocative and

macabre exhibits to be found within the building. Interpretation in the museum takes the form of raw and stark

photographs (many of slain partisans), prison cells

(apparently untouched since the last KGB officers evacuated the building) clothing and technology, documents

and audio commentary in the form of cassette-guided

tours. Lennon and Foley (2000) commented on the issues

of authenticity in examining touristic re-enactments of the

last car journey of President John F. Kennedy and exhibits

on show (in and around the sixth floor of the Dallas Book

Depository) related to his death. The authors noted the

inability of the visitor to be certain that the objects,

documents and other artefacts on display were authentic.

The same can be said for the MGV, however, during

visitation the authors of this paper were permitted to view

a developing exhibition on the second floor of the building

(now open) which the museum Director insisted had not

been altered since the KGB left the building in 1992.

Interpretation in this respect is stark and uncomplicated

and there is some use of basic contemporary exhibitory

techniques, such as audio-visual equipment.

The exhibition comprised basement cells and a further

section presenting exhibits of the dark history of Lithuania

between 1940 and 1941, the history of armed resistance

between 1944 and 1953 and acts of repression carried out

by Soviets. E-mail correspondence from the museum

advises that a third section of the museum will be opened

to the public in late 2005. This will present themes of

prisons and deportation and KG activity between 1954 and

1991. The prison remains largely preserved in its pre-1991

state and visitors can expect to see the rooms of the duty

officer, the search and finger printing rooms, a padded cell

where prisoners were tortured, solitary confinement cells

ARTICLE IN PRESS

526

A. Craig Wight, J. John Lennon / Tourism Management 28 (2007) 519–529

and some 19 detention cells. Temporary thematic exhibitions operate in some cells (MGV, 2003) such as ‘The

Armed Resistance’. Over 220,000 volumes of documents

were discovered in the building relating to KGB activity

(MGV, 2003) and these have been placed in the Special

Archives of Lithuania (LYA).

The retelling of events through such interpretation is

commented on in Lennon and Foley (2000, p.78) with

reference to the commemoration of the death of President

Kennedy in the USA. The authors comment (of interpretation found across three commemorative ‘Kennedy’

sites) that:

In projecting visitors into the past, reality has been

replaced with omnipresent simulation y thus the real is

confined in pure repetition.

Such is the case with the MGV tour that directs and

coerces the visitor towards a conclusion that is based on a

sanitised section of history that is part of a more complex

series of events.

8.4. Interpretation and the presentation of tragedy

The cassette-narrated tour of the museum offers

commentary on the basement (prison cell) section of the

museum. Each cell presents a different exhibitory theme

including the detention cell which was where arrested

prisoners were initially placed before interrogation began.

Most of the cells still contain the original pre-1991 beds

and furniture, and some still display graffiti etched onto the

walls by prisoners. Another cell is filled with shredded

documentation of interrogation and intelligence which the

KGB did not wish to share with the public and

consequently destroyed prior to their evacuation in 1991.

The museum curator claims that this shredded documentation is authentic and that it is on display in order to

represent the KGB’s recording and subsequent censorship

of the sheer scale and volume of crimes committed against

prisoners. Various equipment and technology is on display

such as an old typewriter and communications radio

transmitter used by duty officers.

Other cells display texts and photographs of famous

prisoners who passed through (or died in) the museum.

These include the Catholic Bishop Borisevicius, shot in the

basement in 1946; and partisan leaders Jonas Zemaitis and

Adolfas Ramanauskas who survived for years in the forests

of Soviet Lithuania before their capture and execution by

the KGB in the mid-1950s (Bousfield, 2004). A recent

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) report contained

an interview with former prisoner Juozas Aleksiejunas who

was tortured with sleep deprivation by the KGB just before

the end of World War II in the building as it existed then

(Lane & Wheeler, 2004). One cell in the museum remains

closed as it still contains human remains which are pending

removal. The basement is presented as the last display in

the tour and is where condemned prisoners were taken to

be shot. Indeed, the entire tour is presented as a slow

crescendo of horror, with interest and audience stimulation

increasing in direct proportion to the length of the audiotour.

8.5. Role of the museum

The MGV is a relatively young museum funded by the

Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania. The museum

marked its 10th anniversary in 2002 and has become an

established tourist attraction in Vilnius (MGV, 2003).

There is no newsletter or similar periodical available from

the museum but a promotional leaflet declares:

One of the museum’s objectives is to show the crimes of

the Soviet Regime and to immortalise the freedom

fighters and the victims of the Soviet Genocide (MGV,

2003).

Perhaps the most important role of the museum is to

maintain and extend access to the KGB basement prison

which was constructed in 1940 and remains in an excellent

state of repair. In 1999 several architects and museum staff

drew up plans for an exhibition space in the building.

Interpretation is conveyed through authenticity and preservation of artefacts and rooms. An important on-going

activity for the curators is to restore other parts of the

building, including the interrogation room and some of the

rooms where telephone calls were intercepted.

Given the museums role as an arm of the Genocide and

Resistance Research Centre, one of their objectives is to

market and distribute publications related to the themes

within the museum. A museum representative advised the

authors that four relevant books have been published in

Lithuanian and translated by Museum specialists. A

further publication (Whosoever Saves One Life) is the

only book that addresses the Holocaust. This concentrates

on what is described as the ‘brave actions’ of ethnic

Lithuanians who risked their lives to save members of the

Jewish community from their fate. There is no mention of

collaboration between Lithuanian nationals and the

occupying Nazis, a theme addressed transparently by the

VGM.

8.6. Summary

Table 2 summarises the main themes (identified by the

Museum Director) and representations (identified by the

authors’ observations) portrayed within the MGV.

The use of ‘genocide’ terminology in the MGV context is

concerning when juxtaposed with the less verbally inflated

terminology and context of the nearby Jewish Museum.

‘Genocide’ has been the subject of recent disquiet amongst

Holocaust commentators. The former Secretary-General of

Medicins Sans Frontieres comments in a recent BBC article

on genocide in Darfur (BBC, 2005) that:

The term (genocide) has progressively lost its initial

meaning and is becoming dangerously commonplace.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Craig Wight, J. John Lennon / Tourism Management 28 (2007) 519–529

Table 2

Representation of themes by the Museum of Genocide Victims (KGB)

Theme

Representation

‘Genocide’/human

suffering

Permanent exhibitions of

Artefacts, photographs, maps, texts

relating to Soviet crimes

Stark interpretation including authentic

prison cells and torture rooms

The basement execution room with

authentic artefacts and bullet holes

Amplified sense of suffering through

audio-tour with ‘high’ (or ‘low’) points

Lithuanian armed and

unarmed resistance to

Soviet Repression

First and second floor exhibitions

displaying texts, photographs and other

relevant materials

Publications available in English and

Lithuanian

Uniforms and technological displays

Education for school groups and

visitors

527

commemoration through themes, interpretation, narrative

and events. Both museums represent two distinct ‘dark’

epochs of Lithuanian history and both are esoteric in this

respect, particularly in terms of stimulating interest

amongst locals and the wider ethnic Lithuanian community. Through analysis of these sites a process of ‘selective

interpretation’ (Domic, 2000; Rowehl, 2003) emerges that

is inherent in each museum. Also referred to as ‘hot

interpretation’ (Uzzell, 1989), this has been defined as the

process of creating multiple constructions of the past

(Schouten, 1995) whereby history is never an objective

recall of the past, but is rather a selective interpretation,

based on the way in which we view ourselves in the present.

As Crang (1994, p. 341) notes:

The past is not an immutable or independent object.

Rather it is endlessly revised from our present positions.

History cannot be known save from the always

transitional presenty.there are always multiple constructions of the past.

Graham (2002, p. 2) in the context of heritage concludes:

Lithuanian solidarity and

determination

Publications including ‘Whoever Saves

‘Living History’

Authenticity of most of the rooms and

one Life’ documenting activity of

Lithuanians rescuing Jews

artefacts within the museum

Those who should use the word never let it slip their

mouths. Those who unfortunately do use it banalise it

into a validation of every kind of victimhood.

Contention surrounds the ‘appropriate’ use of such

terminology (and the absence of it in the Jewish Museum).

For example the academic secretary of the Jewish Museum

would prefer that the museum commemorate ‘vicitimisation’, ‘exploitation’ and Soviet ill-treatment rather than

using the term genocide and all that it implies. The

intimation is that a nation that collaborated in the ‘real

genocide’ (sic) of the Jewish race cannot seriously wish to

be regarded as genocide victims themselves particularly if

the crimes committed in each case are meticulously defined.

Yet visitation to the MGV is considerably higher,

suggesting that ‘genocide’ has a certain allure or affinity

for the visiting Lithuanian public and the theme of

‘celebrating Jewish history’, alone does not. This observation builds on the comments made by Siegenthaler (2002)

in noticing the constructions of victimisation and sacralisation that embed themselves in the discourses of ‘dark’ sites

depending on the cultures and communities in which they

are consumed.

9. Analysis of the museums

The above explanatory case studies present key issues

which are unique to each museum, specifically their roles in

y.if heritage is the contemporary use of the past, and if

its meanings are defined in the present, then we create

the heritage that we require and manage it for a range of

purposes defined by the needs and demands of our

present societies.

Lennon and Foley (2000) make reference to selectivity in

their observations of interpretation focussed on ‘dark’

heritage in the Channel Islands. Specifically, the authors

note the key role of the state in sending a small minority of

the British Jewish Community in the Channel Islands to

their deaths and profiting from sales of their businesses.

This aspect of British history, according to the authors

receives very little coverage in terms of interpretation.

Interpretation is instead focussed on the more acceptable

aspects of behaviour during occupation for example, on

events such as liberation and entertainment. Lennon and

Foley (2000, p.76) conclude:

Currently what exists (in terms of interpretation in

Jersey) is a selective perception and level of interpretation that is, at best, misguided and, at worst, deceptive.

A similar situation is certainly notable in Vilnius.

Collective feelings of anger, sorrow and pride (in the

nation’s ‘brave partisan’ movement) can be easily provoked through ‘genocide interpretation’ such as that found

at the MGV. The moral complexity surrounding the

section of history dealing with collaboration and the

Jewish holocaust is accentuated in the way in which this

history is now re-interpreted in the country’s ‘dark’ tourist

attractions. The selectivity is evident in most of the city’s

key museums (including the Lithuanian National Museum

which has no holocaust interpretation) and represents only

that which is easy for the host population to consume. The

idea of a country united in a bloody and prolonged

nationalist struggle against the Soviets is compromised by a

ARTICLE IN PRESS

528

A. Craig Wight, J. John Lennon / Tourism Management 28 (2007) 519–529

period of some 5 years during which the same people

turned on their Jewish neighbours. To quote a representative of the VGM:

ythese units of revolt (anti-Soviet fighters) who took

up arms to fight the retreating red armyy later, in a

week or two (sic) yturned the same guns on their

Jewish neighbours. And Jews were killed.

Central considerations in selective interpretation are

issues of cultural consumption and heritage commodification. These give rise to societal implications including the

exclusion of minority groups and problems with the ethics

of ‘selling’ the past (Domic, 2000). From the two case

studies and literature examined it is suggested that

historical interpretation in both museums is divorced

significantly from the local community and consequently,

the relevance of each museum is affected.

The VGM can be described as a museum offering stark

truths via modest interpretation. Conversely, the MGV

offers a modest account of historical truth via stark

interpretation. The MGV attempt to present an eclectic

representation of history via a miscellany of unspecific

interpretation. This interpretation focuses not only on the

implied primary theme (the ‘genocide’ of partisans) but

also incorporates some representation of the Jewish

holocaust as a national tragedy. This approach is

questioned by the VGM staff who argue that the MGV

focused unfairly and unwisely on the role ethnic Lithuanians played in saving Jewish citizens (for example in the

book ‘Whoever Saves One Life’ on sale in the MGV). It

was suggested that historical facts had been overlooked in

this regard and that the scale and frequency of collaboration between Nazi Germans and ethnic Lithuanians far

outweighed the incidences of Lithuanian intervention in

saving Jewish lives. The MGV’s use of the term ‘Genocide’

in their title is of concern since there is no such reference

made to this activity in either the title or the exhibition

content of the VGM. Stark historical representation is

therefore inherent not only in the palpable mixture of

interpretation found within the MGV but also in the

cultural context of the museum accentuated through the

referencing of ‘Genocide’ in its title and publications.

Domic (2000) argues that communities become substantially affected because of the alignment of heritage with

particular dominant value positions. The dominant value

position identified in Vilnius is the ‘comfort zone’ environment offered by the MGV. Interpretation and narrative

require little moral reflection in this museum. The MGV

presents a holistic image of a one-time persecuted

Lithuanian race and in this regard, it is a more comfortable

interpretive setting for ethnic Lithuanians who can abreact

in an environment of ‘collective pity’. The Jewish

Holocaust Museum on the other hand remains a difficult

commemorative environment for Lithuanians to become

immersed in; provoking feelings of collective guilt and

confusion over a largely fallow section of the country’s

dark past.

10. Conclusion

The ‘dark’ heritage landscape that exists in Lithuania is

dominated by moral complexities surrounding the commemoration of the nations tragic past. The current

situation is a disproportionate slant on this past which

offers the majority of the visiting public a chance to share

in a nation’s solidarity and determination against their

Soviet oppressors. What is distinctly missing from this

activity is an important epoch that remains unchallenged

and un-interpreted in the nation’s collective commemoration of the past.

A collective approach driven by effective, rather than

just quality interpretation may be instrumental in increasing access, education and acceptance of both of these

fascinating museums. However social and ethical taboos

dictate patterns of visitation and non-visitation to the two

museums. Some of this apprehension may be assuaged

through collaboration between the museums and through

the construction and planning of new and contemporary

exhibitory techniques. Successful interpretation consists of

much more than just higher visitor numbers (Rowehl,

2003) but also a degree of satisfaction and enlightenment

that can accompany the museum learning experience. This

is what distinguishes effective from quality interpretation.

Interpretation which is too stark and too intimidating can

prevent physical and intellectual access to a museum’s

collection. It is only through addressing the ethical and

spiritual dichotomies and dealing with selectivity in

historical narrative that an approach of collective memory

can begin to emerge that will replace trepidation and

reluctance.

Acknowledgements

The authors warmly thank Ruta Puisyte, Academic

Secretary of the Vilna Gaon Lithunanian State Jewish

Museum, Eugenijus Peikstenis, Director of the Museum of

Genocide Victims, Vilma Juozeviciute, Senior Specialist of

the Museum of Genocide Victims and Rokas Tracevskis of

the Museum of Genocide Victims. We appreciate the

committed assistance of staff from these museums

throughout the course of this research.

References

Altheide, D. L. (2000). Tracking discourse and qualitative document

analysis. Poetics, 27, 287–299.

Atamukas, S. (2001). The long hard road toward the truth. Lithuanian

Quarterly Journal of Arts and Sciences, 47(4) Internet WWW Page

at URL: http://www.lituanus.org/2001/01_4_03.htm; accessed 14/05/

2005.

Baltic Database (2002). Baltic States Report, 16 May, Vol. 3(16). Internet

WWW Page at URL: www.referl.org/balticreport/2002/05/16-160502.

htlm; accessed 05/04/2005.

BBC (2005). Analysis: Defining genocide. BBC News, Internet WWW

Page at URL: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/3853157.stm; accessed

13/02/2006.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Craig Wight, J. John Lennon / Tourism Management 28 (2007) 519–529

Beech, J. (2000). The enigma of holocaust sites as tourist attractions: The

case of Buchenwald. Managing Leisure, 5, 29–41.

Bousfield, J. (2004). The rough guide to the Baltic states: Estonia, Latvia

and Lithuania. London: Rough Guides.

Clottey, B., & Lennon, R. (2003). Transitional economy tourism:

Lithuanian travel consumers’ perceptions of Lithuania. International

Journal of Travel Research, 5, 295–303.

Crang, M. (1994). On the heritage trail: Maps of journeys to Olde Englande.

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 12, 341–355.

Domic, D. (2000). Heritage consumption, identity, formation and interpretation of the past within post war Croatia. Wolverhampton Business

School Management Research Centre, Working Paper Series 2000.

Dwork, D., & Van Pelt, R. J. (1997). Auschwitz: 1270 to the present.

Norton & Company.

Graham, B. (2002). Heritage as knowledge: Capital or culture? Urban

Studies, 39(5–6), 1003–1017.

Hall, D. (1991). Tourism and economic development in Eastern Europe and

the Soviet Union. London: Belhaven.

Ham, S. H., & Krumpe, E. E. (1996). Identifying audiences and messages

for nonformal environmental education: A theoretical framework for

interpreters. Journal of Interpretation Research, 1(1), 11–23.

Henderson, J. (2000). War as a tourist attraction: The case of vietnam.

International Journal of Tourism Research, 2(4), 269–280.

Hollinshead, K. (1999). Tourism as public culture: Horne’s ideological

commentary on the legerdemain of tourism. International Journal of

Tourism Research, 1, 267–292.

Jaakson, R. (1996). Tourism in transition in post-Soviet Estonia. Annals of

Tourism Research, 23(3), 617–634.

Lane, M., & Wheeler, B. (2004). The real victims of sleep deprivation. BBC

News UK Edition, Internet WWW Page at URL: http://www.bbc.

co.uk/1/hi/magazine/3376951.stm; accessed 05/04/2005.

Laučka, J. B. (1986). The structure and operation of Lithuania’s

parliamentary democracy, 1920–1939. Lithuanian Quarterly Journal

of Arts and Sciences, 32(3) Internet WWW Page at URL: http://

www.lituanus.org/1986/86_3_01.htm; accessed 12/06/2005.

Lennon, J. J. (1996). Marketing eastern European tourist destinations. In

M. Bennet, & A. Seaton (Eds.), Marketing tourism products—

Concepts, issues and cases (pp. 103–149). Hodder and Stoughton.

Lennon, J. J., & Foley, M. (2000). Dark tourism: The attraction of death

and disaster. London, New York: Continuum.

Lithuanian National Tourism Statistics (2004). Internet WWW Page at:

URL: http://www.tourism.lt/statist/inbound.htm; accessed 01/04/2005.

Lopata, R. (1993). The second spring of nations and the theory of

reconstruction of the grand duchy of Lithuania. Lituanas Lithuanian

Quarterly Journal of Arts and Sciences, 39(4) Internet WWW Page at

URL: http://www.lituanus.org/1993_4/93_4_07.htm; accessed 12/092005.

529

Museum of Genocide Victims, Vilnius (MGV) (2003). Promotional

Leaflet.

Museum of Genocide Victims, Vilnius (MGV) (2004). War after War, The

Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, Vilnius.

Puisyte, R. (1997). The mass extermination of jews of jurbarkas in the

provinces of Lithuania during the German Nazi occupation. B.A. thesis,

University of Vilnius (Internet WWW Page at URL: http://www.

shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/Yurburg/bathesis.html; accessed throughout

March–April).

Rowehl, J. (2003). Constructing quality interpretation: The use of

interpretative simulations reconsidered. Arkell European Fellowship

Report 2003.

Schouten, F. F. J. (1995). Heritage as historical reality. In D. T. Herbert

(Ed.), Heritage tourism and society. London: Mansell.

Shackley, M. (2001). Potential futures for Roben Island: Shrine, museum

or theme park? International Journal of Heritage Studies, 7(4),

355–363.

Shaw, D. J. B. (1979). Recreation and the Soviet City. In R. A. Hamilton

(Ed.), The socialist city (pp. 117–143). Chichester: Wiley.

Siegenthaler, P. (2002). Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Guidebooks.

Annals of Tourism Research, 29(4), 1111–1137.

Smith, V. L. (1998). War and thanatourism: An American ethnography.

Annals of Tourism Research, 25(1), 202–227.

Strange, C., & Kempa, M. (2003). Shades of dark tourism: Alcatraz and

Robben Island. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(2), 386–405.

Tunbridge, J. E., & Ashworth, G. J. (1996). Dissonant heritage. The

management of the past as a resource in conflict. Chichester: Wiley.

Uzzell, D. L. (1989). The hot interpretation of war and conflict, in Heritage

Interpretation, Vol. 1. New York: Belhaven Press.

Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum of Lithuania (VGM) (2003). Newsletter 7.

Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum of Lithuania (VGM) (2004). Newsletter 8.

Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum of Lithuania (VGM) (2005). History,

Internet WWW Page at URL: http://www.jmuseum.lt/index.asp?

DL=E&TopicID=6.

Vilnius City Municipality (2005). Internet WWW Page at URL: http://

www.vilnius.lt/new/en/gidas.php; accessed throughout March–April.

Wight, A. C. (2006). Philosophical and methodological praxes in dark

tourism: Controversy, contention and the evolving paradigm. Journal

of Vacation Marketing, 12(2), 119–129.

Wight, A. C., & Lennon, J. J. (2004). Towards an understanding of visitor

perceptions of ‘Dark’ sites: The case of the imperial war museum of the

North, Manchester. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 2(2), 105–122.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd ed.).

Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Zonabend, F. (1992). The monograph in European ethnology. Current

Sociology, 40(1), 49–60.