to - Together For Humanity

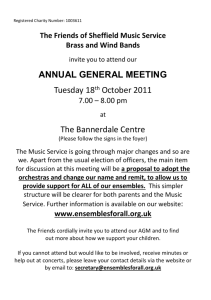

advertisement