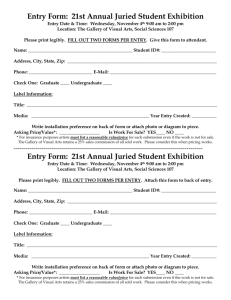

The Gallery, The Artists, The Art

advertisement

Ceeje Revisited Ceeje-- The Gallery, The Artists, The Art; Fidel Danieli Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery April 10- May 13, 1984 Foreword and Acknowledgment The sum total of Ceeje Gallery's contribution to the Los Angeles art situation is probably inestimable. Like many other enterprises in the retail sales of local art, it opened its doors for business, gave it a fair go, survived less than a decade and closed. It created a ripple of sorts by being a controversial center of non-mainstream art, but beyond that it had a different kind of spirit from the other galleries of the 1960's in every area. Located at the north end of La Cienega Boulevard's "gallery row," it was isolated blocks beyond the clustered dealers closer to Melrose. It definitely had a different kind of look- an inviting manner. No blank or intimidating facade, no rabbit warren arrangement of rooms, no indifferent secretary to screen out the hoi polloi, no secret blue chip stock in the shrouded back rooms. There were no solemn veiled mysteries of art only for the connoisseur, no slick salesperson or world weary entrepreneur speaking only with the truly anointed. The look-better yet the feelof Ceeje was of direct, enthusiastic freshness. An open, uncovered front window decorated with an artist's major work or specially executed mural welcomed in the southwestern sun and permitted the visitor a preview glimpse. The room was a spacious long one, lined on one side by a built-in bench that encouraged contemplation and conversation. The dealers' desk was screened only by a partition dividing the space into two areas. Moreover, the owners, Cecil Hedrick and Jerry Jerome, were almost always there to share their faith in their artists. The Ceeje gallery was opened as a crafts gallery in 1959 and was an outgrowth of Cecil Hedrick's ceramic work in the area of architectural commissions. Hedrick's background included a BA degree and postgraduate work in fine arts at the University of California, Los Angeles and several years of teaching. Jerry Jerome was involved in television and was a theater arts major at UCLA. It was a friend in public relations, Florence Mullen, who suggested the joining of their first initials for the gallery's unique name. Another associate was Eleanor Neil (Coppola), whose contacts led to support of several of the artists who became the most widely recognized. Despite the knowledge that few local galleries concentrated on Southern California art in preference to safer, tested European and East Coast examples, and that most major collectors bought in New York, they committed themselves to a core group of artists who came to exemplify the identifiable Ceeje image. This art was figurative with a tendency toward the expressionist and the surreal; it possessed an enormous degree of visual excitement and energy, and was most certainly not in vogue or fashion. They admired artists who, as they describe themselves, "were their own people, renegades and mavericks," and who were "their own mainstreams." They concentrated on artists who were free spirits, as free as themselves. From their own experiences in art and theater they admired directed spontaneity and unplanned discipline. the improvisational, the varied and the diverse, the non-limited were their ideals. Ceeje's dedication to their artists and their belief in Los Angeles art is exemplified by their exhibition record vis a vis New York. Few East Coast artists were shown- Philip Pearlman's first two West Coast shows being notable exceptions. On the other hand, they did expand and operated a New York branch for several years (196567) and drew intrigued recognition and approval of their efforts from notable New York dealers. Then the bloom of the scene faded, the market slumped, the artists became discouraged. In 1967 the dealers, feeling "we had made our mark," closed the New York branch of Ceeje Gallery. They had, however, promised and delivered exposure and promotion. They intuited what was unique about the L.A. art situation, gambled and waited. A quarter century later this exhibition validates many of their choices, both in their belief in the talent of their artists and their total commitment to expressive figurative styles. The majority of their artists were young, and enrolled in the masters' program at UCLA. This in an era when the tacit standards of gallery representation indicated that one should at least be in his mid-thirties and have a string of juried show acceptances and a grant or award or two on his record. It is easy to forget that into the 1970s the general opinion was held that artists had to prove themselves elsewhere before even thinking they might someday be part of a local gallery's stable. The number of the university's painters who had their inaugural solo show or subsequent second or third exhibits at Ceeje is impressive and includes Les Biller, Eduardo Carrillo, Roberto Chavez, Charles Garabedian, Marvin Harden, Louis Lunetta, joan Maffei, Lance Richbourg, Ben Sakoguchi, Jim Urmston and several others. It must be noted, however, that vigor, whether youthful or more senior, was the dealers' criterion. Artists at mid-career or even older were also displayed and later on many members of the UCLA faculty were included. And though the emphasis was on painting, sculptors, assemblage artists and photographers such as Barbara Morgan and Edmund Teske also had their turn. In contrast to the certified products and serial images of other galleries, the shows here most often included diverse media and wildly divergent sizes. Drawings, prints, painted reliefs, threedimensional constructions, small and monumental paintings all jostled for attention in one-person and group theme shows. The formality of aesthetic distance was destroyed further by presentation. Framing was appropriately eclectic and probably determined by relative poverty. Rude and handsome trim contrasted with kitschy charity store frames. One would not be surprised to find that works were painted on found scraps or made to fit frames that were readymade or from the dime store. No limits on what was saleable seemed to have been set; no holds were barred in wrestling for the audience's attention. Even such ephemera as exhibit announcements were totally personal, as opposed to the standardized format imposed on mailers and brochures sent out by other dealers. No formality here. Announcements varied from outsized type on colored paper to the reproduction of the handlettered and freely brushed, with an occasional archly posed and humorous photographed setup. No clearer example of these dealers' open approach (given their stylistic dedication to UCLA and the figurative) is evidenced by the ethnicity of their artists. Long before equal opportunity became a major issue and a legal mandate, their stable included artists whose heritages spanned the Mediterranean to Armenia, Hispanics, a Black, an Asian. Women artists , too, played a regular role in solo and group exhibitions. There was no decision to maintain a balance or ratio of minorities and women, it was, they explain, simply a matter of developing associations wherein the artists, their kin and their families (to a lesser or greater degree) became part of the Ceeje "family." For Hedrick and Jerome there was no boundaries; they did not think that way. The lineage of New York mainstream art runs in a series of links and twists that most acknowledge. European modernism gave rise to Abstract Expressionism; then came the opening provided by Rivers, Johns, Rauschenburg and Kaprow in the mid-to late-1950's. There followed the multiplication of styles in the 1960's as Pop, Geometric, Post-Painterly. Optical, Minimal, Environmental, New Realism and Photo realism, Conceptual,etc. To these, Los Angeles proponents and propagandists asserted adding expressive ceramic,ic work, repeated series of hard edged or geometric styles in nearly identical works, and a careful attention to surfaces and detail using industrial materials and hand- polished craft. Evidently only for local consumption would be any continuation of the rendering of traditional subjects. Still lives, interiors, portraits, figurative works in any non-academic style seemed a dead end or an exhausted vein. The irony is that around 1960 a group of Southern California art students emerged and coalesced around the Ceeje Gallery, and 20 years ahead of its current acceptance by the European and New york art world, they would turn the figurative tradition back in the direction of the personally symbolic. the intimate and autobiographical, the anecdotal and narrative, the mythic. They ransacked art history, as have more recently Germans, Italians and Americans, and turned their attention to the perennial image-making power of emotional illusionism. Their all-consuming interests ran the range from direct naiveté and primitivism of sophisticated ethnic and folk art to the obstinate delineations of Rousseau and the loving care of early Flemish masters. Attractive, too, seemed to be the make believe realism of Uccello and the horrors of Bosch. Pre- Columbian and African sculpture were no strange manifestations. Their surrealism was the mysterious and compulsively hypnotic sort drawn from the synthetic worlds of medieval art, De Chirico and Magritte. Those favoring a painterly attack were inspired by the German Expressionists with both the bold dislocations and heavy outline of Beckmann a clear favorite. Those attracted to full volume drew on everyone, from cowboy artists like Remington and Russell to the mechano-men of Leger and the bombastics of the '20's Mexican muralists, Rivera and Siqueiros. They were willfully awkward or private, purposely clumsy or unabashedly direct. If Ferus Gallery was the "cutting edge" of LA modernism, Ceeje was the ragged edge and several of the artists could parody their own situation and bill themselves as the "rear guard." Hedrick and Jerome felt they were being avant guard in espousing these young radicals and it has taken over a decade-more like twoto prove that their vision was right. Their feelings were honest and true.