PDF - Social Finance

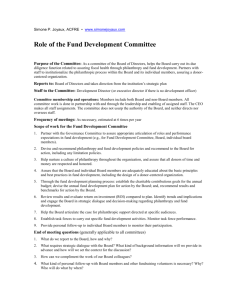

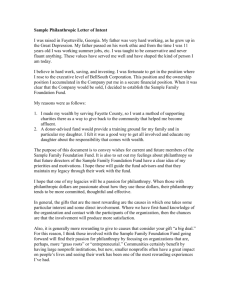

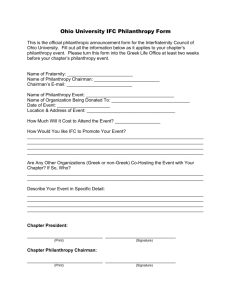

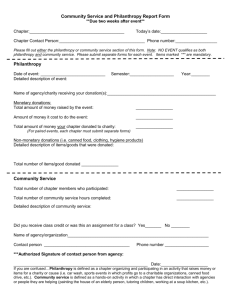

advertisement