Unit Digs into Files, Finds Some People Ready to Talk

advertisement

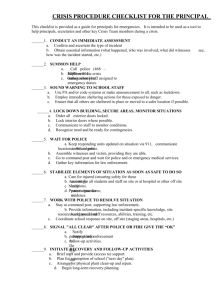

July 24, 2010 Back To Basics: Solving State's Cold Cases Isn't Just About DNA: Unit Digs into Files, Finds Some People Ready to Talk By Karen Florin, The Day, New London, Conn. July 24--Wanted posters that hung in the lobbies of area police departments for years are starting to come down. Detectives haunted by homicide cases long past the "golden hour" when crimes are considered most solvable are getting the satisfaction, finally, of telling victims' family members an arrest has been made. People who may have thought they got away with murder are in prison, awaiting trial, or maybe anticipating the day when the region's cold case investigators knock on their door. Since its inception in October 2009, the Southeastern Connecticut Cold Case Unit has made arrests in cases dating back to 1993 and 1997. More arrests are in the pipeline, according to James Rovella, chief inspector with the Office of the Chief State's Attorney. early stages of the investigation," Massey said. The public often associates cold cases with DNA and other forensic evidence, but witness statements have provided detectives with the biggest breaks in the cold cases they have solved to date. The unit considers three time periods: before, during and after the murder. With the passage of time, people are often more willing to talk. "You break it into concentric circles," Rovella said. "You start with the people closest to the victim and work your way out. Usually in the first circle or two, you find the murderer." Two cases cleared "Times have changed," said Peter Massey, a former Hamden detective who now lectures in forensics at the University of New Haven. "They've matured. They've grown up. Or the pressure they had back then not to say anything is gone. Somebody has passed away, somebody has moved away or somebody is no longer a threat." Many times, the person who is ultimately arrested was part of the original investigation. "The name is in the file someplace, usually in the Re-interviewing a witness 17 years after Bertha Reynolds was found dead at the bottom of the staircase in her Norwich home led to an arrest in that case. In May, the unit charged Irene Reynolds, a 38-year-old mother of three from Baltic, with fatally beating and strangling her mother. Bertha Reynolds' body was found at her home at 84 Laurel Hill Ave., Norwich, on July 19, 1993. After studying the Bertha Reynolds case file, investigators traveled to St. Mary's, Ga., in January to reinterview Reynolds' former roommate, Kim Stone. Stone, who had been questioned many times by Norwich police, was ready to talk. She told the investigators in a taped interview that she saw Irene Reynolds kill her mother. In June, the unit charged 40year-old Dickie Anderson Jr. with killing Renee Pellegrino on June 25, 1997. Pellegrino's body was discovered in a culde-sac off Waterford Parkway South. She had been strangled, her naked body laid out in what the judge who signed the warrant described as an "extreme manner." She was 41. Details of the Pellegrino investigation remain sealed, but according to statements made in court, the case involves DNA from Anderson and another person that was found on Pellegrino's body, inconsistent statements by Anderson over the years, his admission that he was with Pellegrino before she died, and statements from witnesses, including jailhouse informants. In one of the first cases the team looked at, the strangulation of 30-year-old Leandra Wilson in New London on March 6, 1987, the investigators discovered the person who was long suspected in the killing had died. There is more work to be done before the case can be closed, Rovella said. At the moment, the unit is reinvestigating the fatal shooting of 19-year-old Sean Hill in Norwich on June 6, 2006. Hill was murdered during the course of a drug deal and robbery at an apartment complex on Boswell Avenue. Bruce N. Gathers and Gregory Smith pleaded guilty to robbing and assaulting Justin Smith, who was with Hill on the night he was killed, but have not been charged in connection with the murder. They are both in prison. Chief State's Attorney Kevin T. Kane, who prosecuted crimes in New London for 20 years before he was promoted to the statewide position, said local police chiefs were eager to form a unit and tackle their unsolved homicides. The Groton City, Groton Town, New London, Norwich, Stonington and Waterford police have assigned investigators to the unit along with state police from Troop E and the Eastern District Major Crime Squad and the probation and correction departments. Rovella, from Kane's office, and Jack Edwards, a chief inspector with local ties, are supervising the unit. "One of the main functions of government is solving serious crimes," Kane said. "Crimes of this nature, particularly murder and violent sexual assaults, should not go unsolved if we can find the means to solve them." In one cold case that has gone to trial in New London recently, a jury convicted repeat sex offender George M. Leniart this spring of killing 15-year-old April Dawn Pennington in 1996. Defense attorney Norman A. Pattis mounted an aggressive defense of Leniart, but the jury convicted Leniart despite the lack of the victim's body, and with jailhouse "snitches" serving as the state's key witnesses. Two units in state A former Hartford police detective with more than 24 years of experience in homicide investigations, Rovella is the task master who provides weekly assignments to the unit and insists the investigators look first at people other than the main suspects. Rovella also oversees the state's other cold case unit, in the Hartford area, which he said has made about 30 arrests, with only two acquittals, since 1998. The Hartford unit also has helped out with so-called "actual innocence" cases in which DNA testing has proved people were wrongfully convicted. One case involved James C. Tillman, who served 18 years in prison for a sexual assault, kidnapping and robbery. The cold case unit helped identify and prosecute another man, Duane Foster, who eventually pleaded guilty. Rovella has brought a somewhat academic approach to the investigations. The unit takes on a case based on its "solvability." this witness said this at this point and the suspect said this at this point. We get to layer what the witnesses and suspects and police said." Sometimes the investigators study the case for as long as three weeks before they hit the streets to conduct interviews. Unlike the people who initially investigated, the cold case investigators can take their time. "We get to sit back and say, 'Why don't we look at different aspects of these cases?' " Rovella said. "We get to examine the witnesses from a different point of view." 400 unsolved homicides "That means there's physical evidence readily available. There's complete reports in files. There's witnesses that are still alive," he said. An analyst in the Hartford unit organizes the case documents, scans them into a PDF file, and creates a computer disk for each member. The unit also examines computer-generated time lines of each crime. "It's a piece of software that cost us a whole $199," Rovella said. "We can see that Though the governor's office has authorized rewards of up to $50,000 for information that leads to arrests and convictions, rewards traditionally do not play a big part in resolving cold cases, according to Rovella. "They're one of the things in the playbook that we check off as we go," he said. Another thing Rovella asks is that the local departments that initially investigated the crimes "check their egos at the door." He said the unit reinterviews a lot of the same witnesses, hopefully bringing new eyes and a fresh perspective to a case. "It's a reinvestigation," he said. Many of the unit members are seasoned detectives who have worked numerous death cases, but some are patrolmen with limited investigation experience. "We're bringing a major case approach and investigative experience to a lot of these guys in the southeast section that may never see more than three or four homicides in their entire career," Rovella said. The state has about 400 unsolved homicides, according to Rovella, "and the spigot never turns off," he said. In the coming weeks, his office will be distributing playing cards with pictures of 52 homicide victims to the state's prisons and police departments. Like the offer of a monetary reward, this is another way of "stirring the pot," he said. "You've got to get people talking," he said.