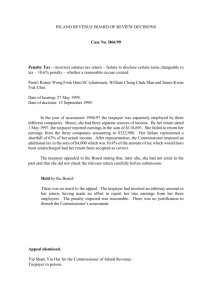

DIPN 11(Revised)

advertisement