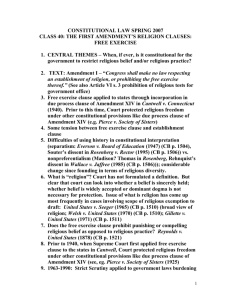

Potential for an Equal Protection Revolution, The

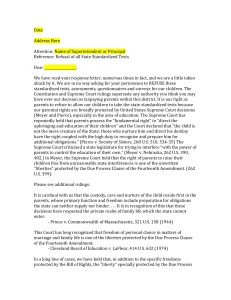

advertisement