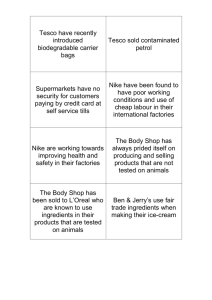

Corporate Responsibility Report

advertisement