in 1980

advertisement

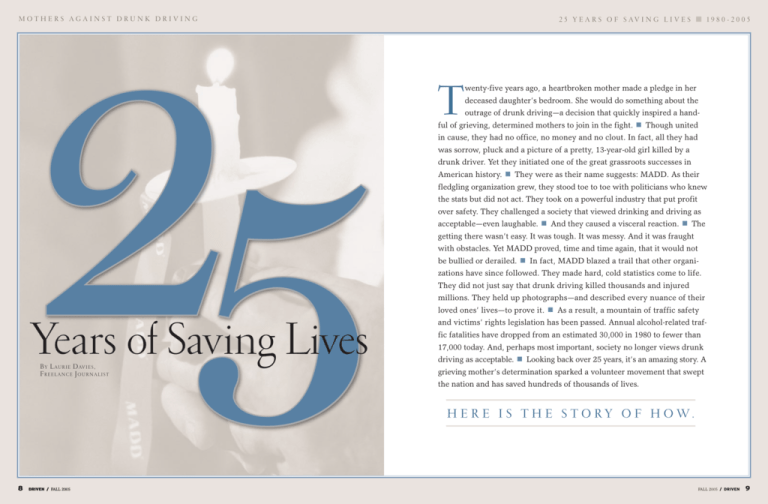

25 MOTHERS AGAINST DRUNK DRIVING Years of Saving Lives B y L au r i e D av i e s , Freelance Journalist DRIVEN / fall 2005 2 5 Y E A R S O F S AV I N G L I V E S n 1 9 8 0 - 2 0 0 5 T wenty-five years ago, a heartbroken mother made a pledge in her deceased daughter’s bedroom. She would do something about the outrage of drunk driving—a decision that quickly inspired a hand- ful of grieving, determined mothers to join in the fight. n Though united in cause, they had no office, no money and no clout. In fact, all they had was sorrow, pluck and a picture of a pretty, 13-year-old girl killed by a drunk driver. Yet they initiated one of the great grassroots successes in American history. n They were as their name suggests: MADD. As their fledgling organization grew, they stood toe to toe with politicians who knew the stats but did not act. They took on a powerful industry that put profit over safety. They challenged a society that viewed drinking and driving as acceptable—even laughable. n And they caused a visceral reaction. n The getting there wasn’t easy. It was tough. It was messy. And it was fraught with obstacles. Yet MADD proved, time and time again, that it would not be bullied or derailed. n In fact, MADD blazed a trail that other organizations have since followed. They made hard, cold statistics come to life. They did not just say that drunk driving killed thousands and injured ­millions. They held up photographs—and described every nuance of their loved ones’ lives—to prove it. n As a result, a mountain of traffic safety and victims’ rights legislation has been passed. Annual alcohol-related traffic fatalities have dropped from an estimated 30,000 in 1980 to fewer than 17,000 today. And, perhaps most important, society no longer views drunk driving as acceptable. n Looking back over 25 years, it’s an amazing story. A grieving mother’s determination sparked a volunteer movement that swept the nation and has saved hundreds of thousands of lives. H ere is the story of ho w . fall 2005 / DRIVEN MOTHERS AGAINST DRUNK DRIVING 2 5 Y E A R S O F S AV I N G L I V E S n 1 9 8 0 - 2 0 0 5 (Left) Candy Lightner, Rep. Robert Matsui (D-CA), Cindy and Laura Lamb, Sen. Claiborne Pell (D-RI) and Rep. Michael Barnes (D-MD) at MADD’s first press conference held Oct. 1, 1980. (Top) First Lady Nancy Reagan at a 1987 National Commission Against Drunk Driving event. (Right) MADD activists from the early years. The Early Days Sue LeBrun-Green remembers the May 1980 day well. Authorities called her real estate office searching for her friend and colleague Candy Lightner. The news was tragic. A hit-and-run driver had struck Candy’s 13-year-old daughter Cari while she was walking to a church carnival. Knocked out of her shoes, Cari landed 125 feet away. She died never knowing what hit her. The hit-and-run driver was turned in by his wife, who was suspicious at his efforts to hide their badly damaged car. “A couple of days later Candy called and said, ‘Sue, we just found out the driver was drunk. Take me over to the DMV. I want to pull his records.’” There, the friends hit a brick wall. “We were told we couldn’t just walk in and pull someone’s driving record. Candy said, ‘This man killed my daughter.’ And they said, ‘It’s not the DMV’s fault.’ They told us we should be talking to judges. Judges’ offices referred us to state agencies. Little by little, people were sending us all over the place. We were actually laying the foundation for MADD,” LeBrun-Green says. The duo quickly learned what traffic-safety advocates already 10 DRIVEN / fall 2005 knew. Drunk driving was not on society’s radar. “Before the 1980s, drinking and driving was how people got home. It was normal behavior,” says MADD chief executive officer and longtime traffic safety advocate Chuck Hurley. Yet tens of thousands were dying and no one but law enforcement and a smattering of researchers and ­government agencies seemed to care. “I was working hard on this issue, just like a lot of us bureaucrats,” says Marilyn Sabin, who was then alcohol coordinator for the California Office of Traffic Safety. Yet she watched DUI bill after DUI bill fail in her state. The feds met a similar fate. “Congress had put $35 million into Alcohol Safety Action Programs around the country, but nothing was happening. Judges were treating it with a wink and a nod,” says Jim Fell, MADD national board member who then worked for the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). “Alcohol was involved in nearly 60 percent of fatal crashes and we were banging our heads against the wall. Then, all of a sudden, a woman named Candy Lightner came along, kicking and screaming about her daughter who had been killed.” A Seismic Shift MADD set up an office—in Cari Lightner’s still-decorated bedroom— and got to work. LeBrun-Green says the early days were hectic. “We gathered information, found other victims through classified ads, mailed newsletters and tried to answer one question for ourselves and other victims: ‘How do I not get the runaround from the system?’” Sabin remembers the first time she heard from the pair. “Candy and Sue came in to find out about the politics and laws in California. As soon as I met them and saw their passion, I knew MADD was a keeper.” In fact, the organization exploded. Victims called faster than they could keep up. Speaking engagements and media requests flooded in. And, politicians returned calls. By September, MADD, or Mothers Against Drunk Drivers as it was originally called, was incorporated. Donations started trickling in—often in $5 and $10 amounts from victims and concerned citizens. The organization was banging loudly on Gov. Jerry Brown’s door to create a drunk ­driving task force. And West Coast met East Coast when Cindy Lamb, whose 5-month-old daughter, Laura, became the nation’s youngest paraplegic as the result of a drunk driving crash, started a Maryland chapter of MADD. Then, on Oct. 1, 1980, Lightner and Lamb riveted the nation during a national press conference on Capitol Hill. It was a seismic shift that catapulted the heartbroken moms into a debate-driving, law-changing force to be reckoned with. “You could literally feel things change at that moment,” says Hurley, who was then working for the National Safety Council. “On that day, public tolerance of drunk ­driving changed forever.” Starting a Wildfire The mothers had struck a chord. Victims of drunk driving and volunteers who simply cared deeply about the cause began to join forces. “We were in every newspaper and on every television station in the country. Housewives were all of a sudden banding together with the idea to change legislation,” LeBrun-Green says. Micky Sadoff was one of those housewives. In 1982, recovering from a head-on alcohol-related crash that injured her and severely injured her husband, Sadoff read a Time magazine article about MADD. It spurred her to start a Milwaukee chapter. “Eighty people showed up at the first meeting,” says Sadoff, who later served as MADD’s national president from 1989 to 1991. “I sat there and said, ‘What do I do now with all these people who want to volunteer?’ So, we started to go to court with families to monitor drunk driving cases.” The same story unfolded nationwide. “MADD was sprouting up in communities all over the country. It wasn’t top-down growth. It was a bunch of small fires that started a wildfire,” she says. Fuel for that fire came from the same source then as it does today. Impassioned volunteers helped each other mourn. They helped each other navigate the criminal justice system. And they worked tirelessly to spare others the pain many of them had endured. MADD’s lifesaving mission often became a lifelong devotion. “It’s pretty humbling to see the long hours that are dedicated to MADD,” says Kyle Ward, MADD’s deputy executive director/director of field operations. “I’ve been at MADD for 16 years and I am still in awe of how much our volunteers give—often for complete strangers.” MADD volunteers also distinguished themselves with the very public way they took their emotion and passion into courtrooms and in front of cameras. “Never before had people expressed their grief in public—this was before Oprah and Dr. Phil. It was groundbreaking what MADD did,” Sabin says. “They did not stop putting a face to the statistics. As a result, in California I watched DUI legislation sail through committees—committees that had voted the same legislation down before MADD had come along.” NHTSA also realized MADD was becoming a major player. “We saw that MADD was really getting the public’s attention,” Fell says. “With our research bolstering their cause, we realized they had the emotional appeal we were lacking.” Mounting Success “All of a sudden, legislators realized they were standing in front of a tidal wave,” says Dean Wilkerson, who served as MADD’s executive director from 1993 to 2004. “They started ­passing laws right and left.” By 1982, new anti-drunk driving laws had been introduced in 35 states and passed in 24. By 1983, 129 new anti-drunk driving laws had passed. With the organization’s growth and increasing efforts came the need for more funds. The first signi­ ficant financial supporter of MADD was an officer of Preferred Risk Insurance Company named Bob Plunk, whose in-laws had been killed by a drunk driver. Preferred Risk later became GuideOne Insurance, which made large donations to MADD in the late 1990s. In 1981, funding increased sub­ stantially when the Leavey Foundation gave MADD $100,000. Mr. Leavey, one of the founders of Farmers Insurance, had had a daughter killed by a drunk driver. The Leavey Foundation would ultimately give MADD $1.3 million in its early years. Also in 1981, NHTSA awarded MADD a $60,000 grant to help start new chapters. Meanwhile, MADD’s numbers, l­egislative successes and funding sources grew. By the end of 1980, there were 11 MADD chapters in California, with six more being formed. By 1982, MADD was 100 chapters strong and President Ronald Reagan announced the Presidential Commission on Drunk Driving and invited MADD to parti­ cipate. Also that year, Congress passed a federal Then-Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole, Candy bill awarding highway Lightner, Sen. Frank Lautenberg (D-NJ) and other dignitaries funds to states with antilook on as President Ronald Reagan signs the Uniform drunk driving efforts. Drinking Age Act into law on July 17, 1984. fall 2005 / DRIVEN 11 MOTHERS AGAINST DRUNK DRIVING Law enforcement officers at the 1990 MADD candlelight vigil First Big Battle In 1983, MADD relocated its national headquarters to Texas in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Meanwhile, the Presidential Commission on Drunk Driving released its recommendations—chief among them a proposal to deny highway funds to states that did not raise the drinking age to 21. This set up MADD’s first big battle. With Ronald Reagan, a states’ rights president, in the White House, the recommendation essentially pitted traffic-safety proponents and spirited moms against a popular president and the cash-loaded alcohol and hospitality industries. MADD, backed by research showing more alcoholrelated teen car crashes occurred in states with legal drinking ages under 21, pushed for the legislation. “From the media’s point of view, it was the perfect underdog story. You had a grassroots person from California with no previous Washington experience taking the town by storm,” Hurley recalls. One Washington insider happened to think the Reagan administration should support the law. “I thought it was very important that the administration be in favor of the law,” says Sen. Elizabeth Dole (R-NC), who served as Transportation Secretary under President Reagan. And she looks back proudly on the 12 DRIVEN / fall 2005 2 5 Y E A R S O F S AV I N G L I V E S n 1 9 8 0 - 2 0 0 5 MADD National President Norma Philips and supporters at the Dec. 9, 1985, finale of the March Across America for MADD event. watershed moment when the president changed his mind. During an Oval Office meeting on the issue, Reagan cut through the clutter—namely reminders from his top advisors that he should stick to his states’ rights stance—and simply asked Secretary Dole a question. “Well, wait a minute,” he said, “doesn’t this help save kids’ lives?” “I said, ‘Yes, Mr. President, it does,’” Dole recalls. “Well then, I support it,” he said. And the next day, Dole announced President Reagan’s support for the measure during a MADD press conference on the Capitol steps. The legislation had already passed the House. But White House support may have been the difference-maker in the Senate, where freshman Sen. Frank Lautenberg (D-NJ) was leading this effort on the pending highway bill. “I was practically told not to come to one fairly well-known New Brunswick (N.J.) restaurant by the owner because of my [support of the] 21-drinking age bill,” says Lautenberg, noting that his home state’s legal drinking age at that time was 18. “And my two younger kids didn’t even want to talk to me. They were in their late teens and said I was killing all their fun.” MADD National President Katherine Prescott speaks out about the need for a Victims’ Rights Amendment to the Constitution. Ultimately, President Reagan signed the Uniform Drinking Age Act into law on July 17, 1984. In fact, Reagan even did a bit of an unplanned commercial spot that day. “My memory is that Candy stuck a MADD button on the president after he signed the bill,” Hurley says. Reagan smiled, photographers loved it and the shot turned up in newspapers nationwide. Growing Up If the early 1980s were a period of emotion and explosion, the rest of the decade was a time for MADD to dig in and establish its footing. By the end of 1984, MADD had 330 chapters in 47 states. This extraordinary growth—held together by the passion and determination of volunteers—had galvanized MADD into a powerful force. Yet, with the growth came growing pains. Amid differences, Lightner left the organization in 1985. And a group of corporate-savvy board members got to work to make MADD more solvent financially. Rob Beck was one of them. “The rapid growth and demands of the organization outgrew the capacity of the initial management to keep up. So we sat down and figured out what we needed to do financially to save the organization,” he says. “They were knights in shining armor really,” says Janice Lord, who came on board as the national director of victim services in 1983. “They loved MADD’s mission. With their corporate knowledge, they also understood budgets and non-profit requirements. They met all night sometimes trying to fix financial issues.” During this time, Lord also got to work developing the structure for MADD’s less-publicized but more implicit goal: serving victims. “I went to MADD with the assumption that there was professional literature about the victim aspect of crashes. There was nothing,” Lord says. She interviewed hundreds of DUI victims and ultimately laid the groundwork for what today has become a model for how to serve victims. “When people hear MADD, they think of political gains. But we have always been about trying to help ­victims be healthy again,” Lord says. Laughter and Tears Meanwhile, the mothers were still in the spotlight. By 1985, Sadoff was a national vice president traveling the country to speak about MADD’s objectives. She and other spokeswomen often paused to laugh about being normal-moms-turnedmedia-magnets. On one occasion, one of them did a television interview—unbelievably— just minutes after having a baby. “She had not made it to the hospital and had literally just given birth to her fifth child at home,” Sadoff says. Yet, with her older children misbehaving in the background and her infant baby swaddled in her arms, the cameras rolled. “Talk about grassroots—we were it,” Sadoff says, adding that, before MADD, none of them had done public speaking. “For my first speech, I wrote the statistics on my hand. Luckily I wasn’t perspiring.” The levity and the deep bond that volunteers shared was a side (Top) MADD supporters plant a tree for those killed and injured in the Kentucky Bus Crash. (Middle) MADD activists on the steps of the U.S. Capitol for MADD’s 10th anniversary. (Bottom) MADD National President Micky Sadoff with President Bush, Sr. of MADD that the public did not always see. “Legislative efforts were always in the spotlight and we had a repu­ tation as a bunch of angry moms,” Sadoff says. “My flip response to that is: ‘Wouldn’t you be angry?’ But the truth is that MADD from the very start has been men and women, young and old, victims and non-victims who care about each other and know they can make a difference.” Their camaraderie also provided a needed balance to those times when the tragedy of drunk driving drove them to their knees. May 14, 1988, was one of those days. On that fateful day in Kentucky, a drunk driver slammed head-on into a bus returning home from a church outing. The bus burst into flames, and 24 young people and three adults perished in the inferno. Thirty more were injured. The Kentucky Bus Crash was the worst alcohol-related crash in U.S. history. MADD immediately dispatched a crisis team to Kentucky. “MADD was the only one out there that understood the grief these people were experiencing. We knew that their grief was compounded by the fact that someone had made the choice to get behind the wheel of a car after drinking, and that their loved ones had died because a crime had been committed,” says Millie Webb, MADD national president from 2000 to 2002, who herself was badly burned in a 1971 alcohol-related crash that killed her 4-year-old daughter and 19-month-old nephew. In that 1971 crash, Webb had been burned on nearly 73 percent of her body, leaving scars that comforted one young victim. The tender picture of Webb holding a little girl who survived the Kentucky bus crash pierces to the heart and soul of who MADD is. fall 2005 / DRIVEN 13 MOTHERS AGAINST DRUNK DRIVING “She would rub my burn scars and talk and talk about how terrible it was to watch her friends burn alive. She felt at ease with my arms around her,” Webb says. “There is beauty in that. Scars are ugly. But she saw me living with them and knew that she would too.” Early 1990s By the time 1990 arrived, MADD’s lifesaving message was paying off: Alcohol-related traffic fatalities had dropped to about 22,400. While still unacceptable, the total had dropped by nearly 8,000 since MADD’s inception a decade earlier. MADD also was holding victim assistance training workshops across the country and working hard for ­better victims’ rights. Pursuing an objective that began in 1984, MADD continued to push for a federal .08 blood alcohol concentration (BAC) standard. Four states lowered their illegal BAC laws from .10 to .08 by the end of 1990. Always underscoring this and other MADD efforts was a singular purpose. “We didn’t fight to bring our children back. We fought so other people wouldn’t hurt,” Webb says. So the battle to make America’s roads safer continued. In 1991, MADD issued its first (Left) MADD National President Katherine Prescott at the 1996 Rating the States press event. (Right) Youth activists at the 2000 MADD National Youth Summit to Prevent Underage Drinking. 14 DRIVEN / fall 2005 Rating the States report, which rated state and national anti-drunk driving efforts and garnered significant media attention. Wildly popular and widely read, subsequent Rating the States reports would follow in 1993, 1996, 1999 and 2002. By 1992, a Gallup survey revealed that Americans cited drunk driving as the No. 1 problem on the nation’s highways. And there was progress: The release of the 1993 Fatal Accident Reporting System statistics showed that alcohol-related traffic fatalities had dropped to a 30-year low. “By the 1990s, MADD had become well-balanced,” Hurley says, adding that emotion, stronger financial footing and an internal ­doctrine to support only policies backed by science propelled MADD to continued success. While MADD’s national clout was now firmly established, it was local and state volunteers who gave the organization a true national voice— one battle and one region at a time. Bob Shearouse, former national director of public policy, remembers the eye-opening moment when he began volunteering at the local level. “When I started, we didn’t have an open container law in Georgia. You could ride down the road with a drink in one hand and the steering wheel in another. I thought I would go to the legislature, point that out and they’d say, ‘You’re kidding,’ and pass a law. It didn’t happen that way.” It took time, manpower and tireless dedication. But state by state, key antidrunk driving legislation and victims’ rights bills were ­getting through. “The role of victims and volunteers cannot be understated in the arena of public policy,” Shearouse says. “They are the ones who had the commitment and passion to drive this 2 5 Y E A R S O F S AV I N G L I V E S n 1 9 8 0 - 2 0 0 5 movement. They got the laws that are saving lives today.” Sometimes they got creative. “I remember when MADD Florida was having a particularly hard time with legislation,” he says. “In the Capitol rotunda they placed a pair of shoes worn by each drunk driving ­victim killed in Florida the year before. There were 1,100 pairs of baby shoes, toddler shoes, men’s shoes and women’s shoes.” Undoubtedly, more than a few ­legislators swallowed hard on their way to their Capitol offices that day. Diversifying Funds Also in the 1990s, former Executive Director Dean Wilkerson and others engineered a pivotal shift during which MADD diversified its public fundraising to include direct mail, licensing agreements, sponsorships and other avenues. During this period, many cor­ porations allied with MADD both financially and ideologically through support of MADD’s programs. Auto­ makers such as General Motors, DaimlerChrysler and Volkswagen jumped on board as well as insurance companies including Allstate, Nation­ wide, State Farm and—one of MADD’s earliest partners—GuideOne. Stonehenge, Ltd., developed a popular anti-drunk driving neckwear line. Citibank kicked in a substantial contribution. Dial America dialed in to the cause—and has contributed a whopping $25 million from magazine sales to MADD in the past decade. From Budget, Avis and Alamo to General Mills and Coca-Cola, MADD began popping up in product sponsorships everywhere. By 1994, The Chronicle of Philanthropy released a survey showing that MADD was the most popular charity in America. Yet, holding up a mirror to the grassroots success that MADD has always been, most of MADD’s financial support still came in individual donations. “The reality is, even though we’ve gotten great corporate support, the heart and soul of MADD has been the American public. Individual donations comprise nearly half of MADD’s total revenues,” says Bobby Heard, former national director of programs and development. Youth movement Coinciding with this time in MADD’s history was a growing focus to protect youth from the dangers of drinking. In 1995, at the request of then-National President Beckie Brown, MADD convened a Commission on Youth—a move that set the course for MADD’s future efforts to prevent underage drinking. “It was at that time that we made the strategic decision to partner with youth to combat the No. 1 youth drug problem, which is underage drinking,” Heard says. “By working closely with them, we could help them see that they could be a part of the solution.” MADD kicked off a flurry of successful youth-oriented programs— including MADD’s multimedia school assembly shows, Youth In Action and Summer Power Camps. On the national stage, in 1995 the Zero Tolerance for Youth Act was adopted by Congress, inducing states to make it illegal for those under 21 to drive with alcohol in their system. And in 1997, MADD held its first of two national Youth Summits to Prevent Underage Drinking, which assembled young people from every U.S. congressional district in Washington, D.C., to brainstorm solutions to the underage drinking problem. The summit concluded with each parti­ cipant meeting with his or her ­representative or senator. In fact, as a result of meeting a youth delegate from West Virginia, Sen. Robert Byrd appropriated $25 mil­ lion to combat underage drinking. “I am convinced that because of one teenager’s persuasiveness, Sen. Byrd continues to champion that federal funding today,” Shearouse says. In 1998, MADD elected its first youth representative to its national board of directors, and, in 1999, the organization changed its mission statement to reflect its youth emphasis. In addition to stopping drunk driving and serving victims, a goal to prevent underage drinking was added. This mission is bolstered by research showing the devastating effects of underage alcohol use. “Nearly 29 percent of all high school students nationally begin to drink before the age of 13,” says Ralph Hingson, director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s Division of Epidemiology and Prevention Research. “Those who do are 10 times more likely to become ­frequent binge drinkers.” Additionally, studies show that alcohol-dependent kids have less frontal-lobe brain activity than their non-alcohol-dependent counterparts. Today, MADD offers a continuum of youth programs aimed at reducing underage drinking. The push for .08 Meanwhile, by the late 1990s, the drive to establish .08 percent as the illegal BAC in every state was still in high gear. Laser-focused on “.08” for years, MADD continued to make known (Left) Youth in Action teens speak to the media about underage drinking prevention at a 1996 event. (Middle) A MADD activist signs his support of a national .08 BAC law. (Right) MADD National President Karolyn Nunnallee at the Dec. 29, 1999, event unveiling MADD’s HigherRisk Driver program. the evidence showing that higher BAC levels increased fatal crash risk. Some states quickly moved to lower their BAC levels to .08. And volunteers who worked indefatigably to promote the lifesaving legislation began to see success. Many states, however, did not budge. One key piece of research was a 1996 study published by Hingson in the American Journal of Public Health estimating that a nationwide adoption of .08 percent BAC would result in at least 500 fewer alcohol-related deaths annually. A side story regarding this research once again illustrates what MADD has done so well throughout its 25-year history: It puts a face to the statistics. In this case, Hingson asked then-President Millie Webb if he could dedicate that journal article to her 4-year-old daughter, Lori, who had died at the hands of a .08 driver. Although 75 percent of her little body was critically burned, Lori had survived in full, excruciating fall 2005 / DRIVEN 15 MOTHERS AGAINST DRUNK DRIVING 2 5 Y E A R S O F S AV I N G L I V E S n 1 9 8 0 - 2 0 0 5 A new millennium The Patterson family of Huntingtown, Md., First Lady Hillary Clinton, and MADD National Presidents Karolyn Nunnallee and Millie Webb at the White House for the 1999 Tie One On For Safety campaign. consciousness for two weeks. “She was alert—so alert that she asked for her allowance,” Webb says. Lori died before she got to spend her $3 allowance. And for 20 years, Webb carried those three bills with her. At a board meeting following the publication of Hingson’s study, Webb presented Hingson with one of the dollars. “I was left speechless. I was completely…I don’t know how quite to express it,” Hingson says, his voice still breaking at the memory. “It was stunning to receive such a deeply personal gift from her.” Closing in While such tender stories did not make headlines, they were always at the heart of the 16-year fight. By 1998, 17 states had adopted the .08 percent BAC—and a growing number of studies showed that the measure was saving lives. Despite substantial opposition from the alcohol industry, hotel and restaurant associations, and even from some citizens opposed to MADD’s objectives, MADD worked for legislation that would withhold federal highway funds from states that did not adopt the .08 percent law. Sen. Lautenberg was again at the forefront. “Once we got the 21 drinking age bill through and we estimated we 16 DRIVEN / fall 2005 Activists on Capitol Hill during MADD’s 20th anniversary in 2000. had saved about 20,000 young people from dying on the highways, that was something everyone cheered. But it didn’t make passing .08 an easier task,” says Sen. Lautenberg, who wrote the Senate’s .08 provision. In fact, opponents skillfully used scare tactics and misinformation. “From talk shows to the news media, the opposition had everyone believing this would usher in prohibition. They said if MADD got .08, we’d be back the next year for .04, which, of course, was not true,” Shearouse says. Meanwhile, he watched while House committee members escorted alcohol industry representatives into committee meetings while victims sat outside because there “wasn’t room for them.” Finally, in 1998, the .08 measure passed in the Senate but failed in the House, setting up the last big push. “I was doing a talk show in Ohio and a liquor lobbyist called in and attacked me—I mean really attacked me,” Webb says. “He said we wouldn’t be satisfied until couples couldn’t even have one drink over dinner together. He called me a prohibitionist. I told him, ‘I’ve been burned alive because of a .08 driver. I buried my 4-year-old. I have scientific evidence behind me. What have you got?’” Ultimately, Congress sent legislation to the White House mandating states pass .08 BAC laws or else lose highway funding. For Webb, the legislation brought 29 years of frustration, grief and activism full circle. “Finally, after all the studies and us sticking to our guns at the local, state and national level, the whole world knew that .08 was a level where no one should be on the roadway. I felt that my daughter had not died in vain,” she says. In fact, when Webb stood in the Oval Office on Oct. 23, 2000—the day President Clinton signed the legislation into law—she flashed back to the aftermath of her 1971 crash. “For a minute I was back in that ICU. I had just learned my child was dead and I was burned so badly I couldn’t even raise my hand to wipe my tears. Then I looked around the Oval Office. It was a miracle— not just for me but for so many other victims.” Although she did not plan to tell her story at the ensuing Rose Garden reception, Webb privately told the president what the law meant to her. “President Clinton looked me in the eye and said, ‘Millie, this is what the world needs to hear.’ And he walked out to the Rose Garden with me, holding my hand.” Bolstered by the president’s words and her own commitment to spare others her pain, she did indeed tell her story that day. By 2000, MADD’s efforts to educate the public were making a definite difference—a Gallup survey revealed that 97 percent of the public recognized MADD’s name. States had passed thousands of laws, and by 2002, alcohol-related traffic deaths were at 17,524. However, this was a disturbing increase from a 1999 low of 16,572. Furthermore, about half a million people were still being injured in drunk driving crashes. Consequently, in 2002, MADD convened a National Impaired Driving Summit, bringing trafficsafety experts together to strategize the most effective measures to reverse the rising trend in alcoholrelated traffic deaths and injuries. The summit resulted in a sciencebased eight-point action plan designed to reinvigorate the fight against drunk driving. “The fact that they are focused on initiatives supported with rigorous scientific evidence enhances their credibility with legislators (Left) President Clinton and other dignitaries applaud MADD National President Millie Webb at the Oct. 23, 2000, Rose Garden reception that followed the signing of the national .08 BAC legislation. (Right) MADD National President Wendy Hamilton testifies before the U.S. House Subcommittee on Education Reform on Feb. 11, 2004. and ­government organizations,” Hingson observes. In fact, by 2003, MADD’s credibility in Washington, D.C., was evident as MADD National President Wendy Hamilton was asked several times to testify before Congressional leaders on the reauthorization of the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21), a six-year highway funding bill. Meanwhile, MADD has steadily built upon its legacy of strong victim services—today training victim advocates with a more formalized curriculum and working to make it easier for victims to get the help they need. Looking back, looking ahead It’s inspiring to trace MADD’s remarkable journey 25 years down the road. With broken hearts and meager beginnings, the early leaders of MADD ignited a movement that has helped save more than 300,000 lives in 25 years. “MADD did it. They brought their broken hearts to the public,” Sen. Lautenberg says. “As hard as I or any other legislator might work, it doesn’t get any better than MADD because it is so heartfelt.” Sen. Dole agrees. “They are grassroots heroes really. They have helped change the climate of safety in America and tens of thousands of lives have been saved.” Ordinary Americans no longer grab “one for the road,” and “designated driver” is a household term. The organization, which now boasts approximately 2 million ­ embers and supporters, has m changed laws and behavior. But not content to bask in the glow of its silver anniversary, MADD knows that key battles still remain. Loopholes in underage drinking laws make it easy for youth to buy, possess and drink alcohol. Law enforcement agencies need more resources to do their jobs effectively. And, in perhaps the ultimate insult to victims, some courtrooms still slap offenders on the wrist. So, in some ways the story con­ tinues where it began—with a relentless pursuit for better laws, better enforcement and stiffer punishments. But the story of MADD has always been one of triumph over adversity. They have pushed for laws no one ever thought would pass. They have dedicated years—in some cases entire lives—to making America’s roads safer despite the arguments of those with other agendas. And they have helped thousands upon thousands of survivors survive. The casual observer might say that MADD had its day or that the drinking and driving problem has been solved. Yet, as strong and determined as ever, MADD knows the heartache of those who can testify otherwise. Drunk driving forces parents to bury their children—and children to bury their parents. It strips thriving families of their health and livelihood. It crunches much more than metal—it crushes dreams. And it is 100 percent preventable. So, as long as drunk drivers endanger lives, MADD will be there fighting for safer, sober roads. They will work to win the hearts of adolescents and young drivers, who hold the keys to the future of traffic safety in America. And they will take on those with money, power and influence who argue for special interests and against public safety. And they will win. One saved life at a time…they will win. fall 2005 / DRIVEN 17