here - Queen's University Belfast

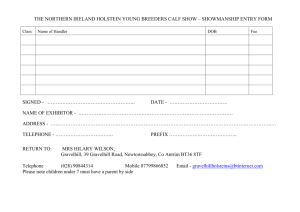

advertisement