Conflicts of Interest and the Case of Auditor

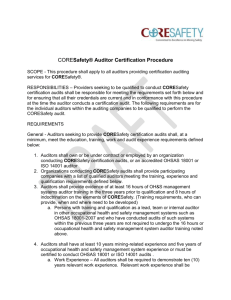

advertisement