Examining Rudyard Kipling's Attitude Towards the First World War

advertisement

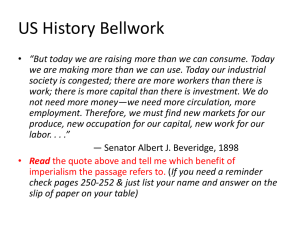

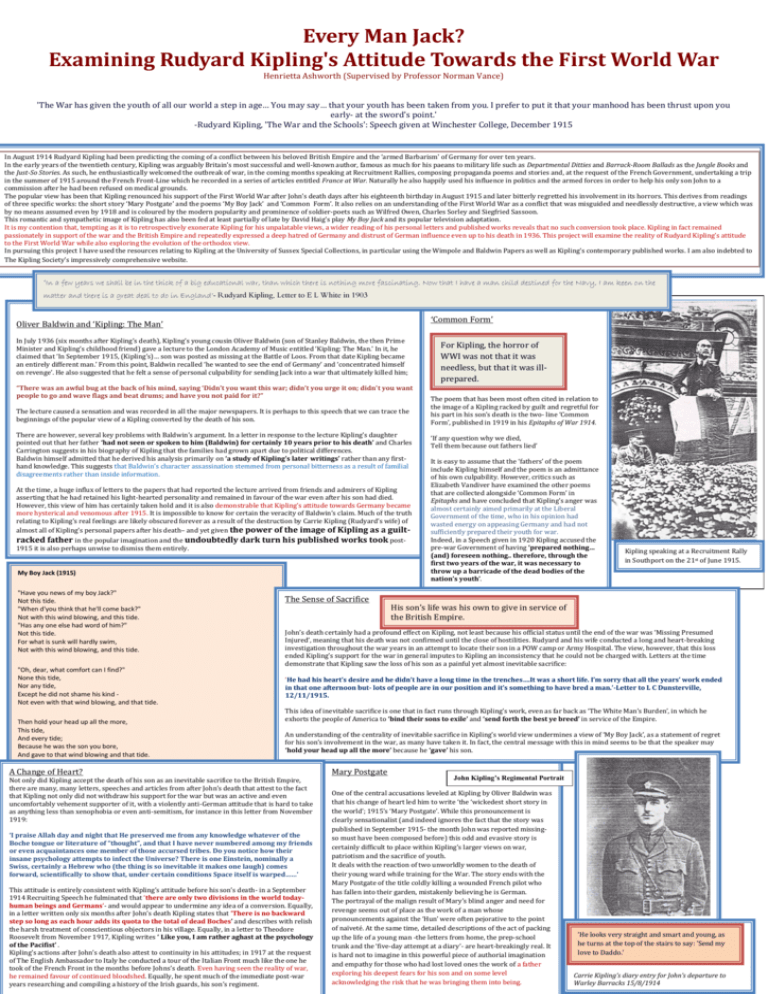

Every Man Jack? Examining Rudyard Kipling's Attitude Towards the First World War Henrietta Ashworth (Supervised by Professor Norman Vance) 'The War has given the youth of all our world a step in age… You may say… that your youth has been taken from you. I prefer to put it that your manhood has been thrust upon you early- at the sword's point.' -Rudyard Kipling, 'The War and the Schools': Speech given at Winchester College, December 1915 In August 1914 Rudyard Kipling had been predicting the coming of a conflict between his beloved British Empire and the ‘armed Barbarism' of Germany for over ten years. In the early years of the twentieth century, Kipling was arguably Britain’s most successful and well-known author, famous as much for his paeans to military life such as Departmental Ditties and Barrack-Room Ballads as the Jungle Books and the Just-So Stories. As such, he enthusiastically welcomed the outbreak of war, in the coming months speaking at Recruitment Rallies, composing propaganda poems and stories and, at the request of the French Government, undertaking a trip in the summer of 1915 around the French Front-Line which he recorded in a series of articles entitled France at War. Naturally he also happily used his influence in politics and the armed forces in order to help his only son John to a commission after he had been refused on medical grounds. The popular view has been that Kipling renounced his support of the First World War after John’s death days after his eighteenth birthday in August 1915 and later bitterly regretted his involvement in its horrors. This derives from readings of three specific works: the short story ‘Mary Postgate’ and the poems ‘My Boy Jack’ and ‘Common Form’. It also relies on an understanding of the First World War as a conflict that was misguided and needlessly destructive, a view which was by no means assumed even by 1918 and is coloured by the modern popularity and prominence of soldier-poets such as Wilfred Owen, Charles Sorley and Siegfried Sassoon. This romantic and sympathetic image of Kipling has also been fed at least partially of late by David Haig’s play My Boy Jack and its popular television adaptation. It is my contention that, tempting as it is to retrospectively exonerate Kipling for his unpalatable views, a wider reading of his personal letters and published works reveals that no such conversion took place. Kipling in fact remained passionately in support of the war and the British Empire and repeatedly expressed a deep hatred of Germany and distrust of German influence even up to his death in 1936. This project will examine the reality of Rudyard Kipling’s attitude to the First World War while also exploring the evolution of the orthodox view. In pursuing this project I have used the resources relating to Kipling at the University of Sussex Special Collections, in particular using the Wimpole and Baldwin Papers as well as Kipling’s contemporary published works. I am also indebted to The Kipling Society’s impressively comprehensive website. ‘In a few years we shall be in the thick of a big educational war, than which there is nothing more fascinating. Now that I have a man child destined for the Navy, I am keen on the matter and there is a great deal to do in England’- ‘Common Form’ Oliver Baldwin and ‘Kipling: The Man’ In July 1936 (six months after Kipling’s death), Kipling’s young cousin Oliver Baldwin (son of Stanley Baldwin, the then Prime Minister and Kipling’s childhood friend) gave a lecture to the London Academy of Music entitled ‘Kipling: The Man.’ In it, he claimed that ‘In September 1915, (Kipling’s)… son was posted as missing at the Battle of Loos. From that date Kipling became an entirely different man.’ From this point, Baldwin recalled ‘he wanted to see the end of Germany’ and ‘concentrated himself on revenge’. He also suggested that he felt a sense of personal culpability for sending Jack into a war that ultimately killed him; “There was an awful bug at the back of his mind, saying ‘Didn’t you want this war; didn’t you urge it on; didn’t you want people to go and wave flags and beat drums; and have you not paid for it?” The lecture caused a sensation and was recorded in all the major newspapers. It is perhaps to this speech that we can trace the beginnings of the popular view of a Kipling converted by the death of his son. There are however, several key problems with Baldwin’s argument. In a letter in response to the lecture Kipling’s daughter pointed out that her father ‘had not seen or spoken to him (Baldwin) for certainly 10 years prior to his death’ and Charles Carrington suggests in his biography of Kipling that the families had grown apart due to political differences. Baldwin himself admitted that he derived his analysis primarily on ‘a study of Kipling’s later writings’ rather than any firsthand knowledge. This suggests that Baldwin’s character assassination stemmed from personal bitterness as a result of familial disagreements rather than inside information. At the time, a huge influx of letters to the papers that had reported the lecture arrived from friends and admirers of Kipling asserting that he had retained his light-hearted personality and remained in favour of the war even after his son had died. However, this view of him has certainly taken hold and it is also demonstrable that Kipling’s attitude towards Germany became more hysterical and venomous after 1915. It is impossible to know for certain the veracity of Baldwin’s claim. Much of the truth relating to Kipling’s real feelings are likely obscured forever as a result of the destruction by Carrie Kipling (Rudyard’s wife) of almost all of Kipling’s personal papers after his death– and yet given the power of the image of Kipling as a guiltracked father in the popular imagination and the undoubtedly dark turn his published works took post1915 it is also perhaps unwise to dismiss them entirely. My Boy Jack (1915) "Have you news of my boy Jack?" Not this tide. "When d'you think that he'll come back?" Not with this wind blowing, and this tide. "Has any one else had word of him?" Not this tide. For what is sunk will hardly swim, Not with this wind blowing, and this tide. "Oh, dear, what comfort can I find?" None this tide, Nor any tide, Except he did not shame his kind Not even with that wind blowing, and that tide. Then hold your head up all the more, This tide, And every tide; Because he was the son you bore, And gave to that wind blowing and that tide. The Sense of Sacrifice For Kipling, the horror of WWI was not that it was needless, but that it was illprepared. The poem that has been most often cited in relation to the image of a Kipling racked by guilt and regretful for his part in his son’s death is the two- line ‘Common Form’, published in 1919 in his Epitaphs of War 1914. ‘If any question why we died, Tell them because out fathers lied’ It is easy to assume that the ‘fathers’ of the poem include Kipling himself and the poem is an admittance of his own culpability. However, critics such as Elizabeth Vandiver have examined the other poems that are collected alongside ‘Common Form’ in Epitaphs and have concluded that Kipling’s anger was almost certainly aimed primarily at the Liberal Government of the time, who in his opinion had wasted energy on appeasing Germany and had not sufficiently prepared their youth for war. Indeed, in a Speech given in 1920 Kipling accused the pre-war Government of having ‘prepared nothing… (and) foreseen nothing.. therefore, through the first two years of the war, it was necessary to throw up a barricade of the dead bodies of the nation’s youth’. Kipling speaking at a Recruitment Rally in Southport on the 21st of June 1915. His son’s life was his own to give in service of the British Empire. John’s death certainly had a profound effect on Kipling, not least because his official status until the end of the war was ‘Missing Presumed Injured’, meaning that his death was not confirmed until the close of hostilities. Rudyard and his wife conducted a long and heart-breaking investigation throughout the war years in an attempt to locate their son in a POW camp or Army Hospital. The view, however, that this loss ended Kipling’s support for the war in general imputes to Kipling an inconsistency that he could not be charged with. Letters at the time demonstrate that Kipling saw the loss of his son as a painful yet almost inevitable sacrifice: ‘He had his heart’s desire and he didn’t have a long time in the trenches….It was a short life. I’m sorry that all the years’ work ended in that one afternoon but- lots of people are in our position and it’s something to have bred a man.’-Letter to L C Dunsterville, 12/11/1915. This idea of inevitable sacrifice is one that in fact runs through Kipling’s work, even as far back as ‘The White Man’s Burden’, in which he exhorts the people of America to ‘bind their sons to exile’ and ‘send forth the best ye breed’ in service of the Empire. An understanding of the centrality of inevitable sacrifice in Kipling’s world view undermines a view of ‘My Boy Jack’, as a statement of regret for his son’s involvement in the war, as many have taken it. In fact, the central message with this in mind seems to be that the speaker may ‘hold your head up all the more’ because he ‘gave’ his son. A Change of Heart? Not only did Kipling accept the death of his son as an inevitable sacrifice to the British Empire, there are many, many letters, speeches and articles from after John’s death that attest to the fact that Kipling not only did not withdraw his support for the war but was an active and even uncomfortably vehement supporter of it, with a violently anti-German attitude that is hard to take as anything less than xenophobia or even anti-semitism, for instance in this letter from November 1919: ‘I praise Allah day and night that He preserved me from any knowledge whatever of the Boche tongue or literature of “thought”, and that I have never numbered among my friends or even acquaintances one member of those accursed tribes. Do you notice how their insane psychology attempts to infect the Universe? There is one Einstein, nominally a Swiss, certainly a Hebrew who (the thing is so inevitable it makes one laugh) comes forward, scientifically to show that, under certain conditions Space itself is warped……’ This attitude is entirely consistent with Kipling’s attitude before his son’s death- in a September 1914 Recruiting Speech he fulminated that ‘there are only two divisions in the world todayhuman beings and Germans’- and would appear to undermine any idea of a conversion. Equally, in a letter written only six months after John’s death Kipling states that ‘There is no backward step so long as each hour adds its quota to the total of dead Boches’ and describes with relish the harsh treatment of conscientious objectors in his village. Equally, in a letter to Theodore Roosevelt from November 1917, Kipling writes ‘ Like you, I am rather aghast at the psychology of the Pacifist’ . Kipling’s actions after John’s death also attest to continuity in his attitudes; in 1917 at the request of The English Ambassador to Italy he conducted a tour of the Italian Front much like the one he took of the French Front in the months before Johns’s death. Even having seen the reality of war, he remained favour of continued bloodshed. Equally, he spent much of the immediate post-war years researching and compiling a history of the Irish guards, his son’s regiment. Mary Postgate John Kipling’s Regimental Portrait One of the central accusations leveled at Kipling by Oliver Baldwin was that his change of heart led him to write ‘the ‘wickedest short story in the world’; 1915’s ‘Mary Postgate’. While this pronouncement is clearly sensationalist (and indeed ignores the fact that the story was published in September 1915- the month John was reported missingso must have been composed before) this odd and evasive story is certainly difficult to place within Kipling’s larger views on war, patriotism and the sacrifice of youth. It deals with the reaction of two unworldly women to the death of their young ward while training for the War. The story ends with the Mary Postgate of the title coldly killing a wounded French pilot who has fallen into their garden, mistakenly believing he is German. The portrayal of the malign result of Mary’s blind anger and need for revenge seems out of place as the work of a man whose pronouncements against the ‘Hun’ were often pejorative to the point of naïveté. At the same time, detailed descriptions of the act of packing up the life of a young man -the letters from home, the prep-school trunk and the ‘five-day attempt at a diary’- are heart-breakingly real. It is hard not to imagine in this powerful piece of authorial imagination and empathy for those who had lost loved ones the work of a father exploring his deepest fears for his son and on some level acknowledging the risk that he was bringing them into being. 'He looks very straight and smart and young, as he turns at the top of the stairs to say: 'Send my love to Daddo.' Carrie Kipling’s diary entry for John’s departure to Warley Barracks 15/8/1914