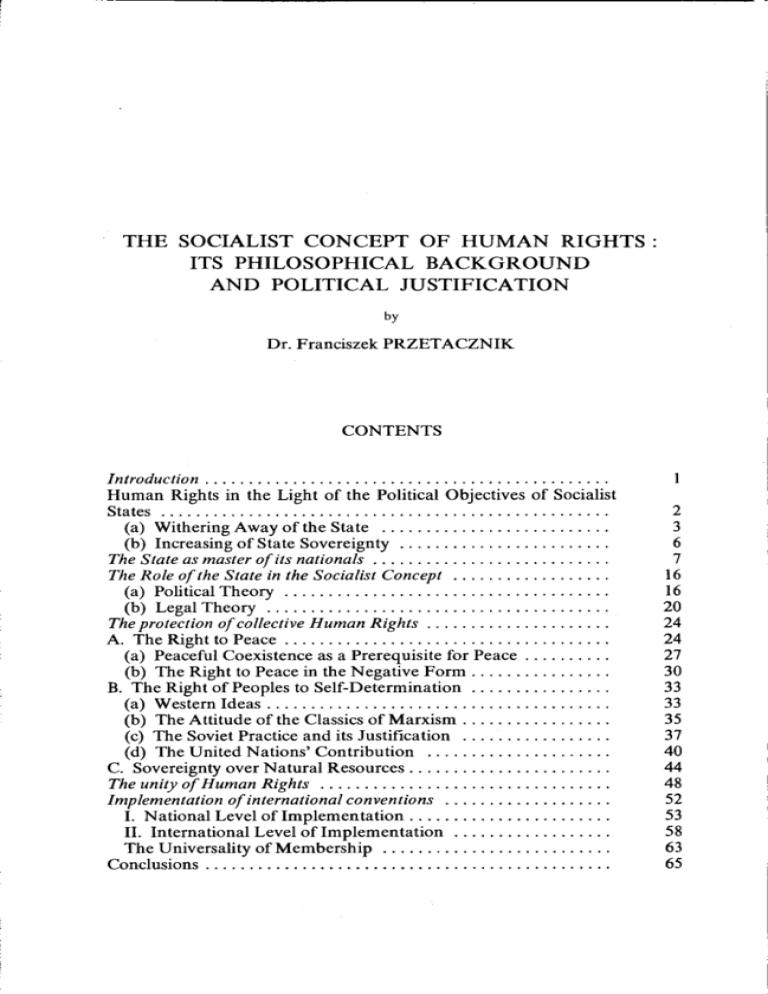

the socialist concept of human rights : its philosophical background

advertisement