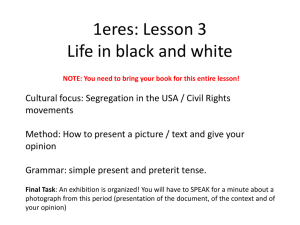

Conceptions of Law in the Civil Rights Movement

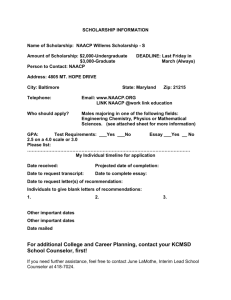

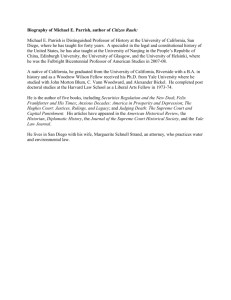

advertisement