The Art of Persuasion and Logical Fallacies Writing

advertisement

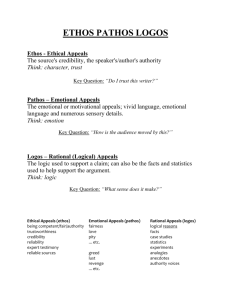

The Art of Persuasion and Logical Fallacies Writing Program Over 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher, Aristotle, wrote The Art of Rhetoric, a book that explains the methods used to persuade audiences. According to Aristotle, there are three types of “appeals” that speakers and writers can employ. These are ethical appeals (ethos), emotional appeals (pathos), and logical appeals (logos). Ethical Appeals, or ethos: An ethical appeal is all about the writer’s credibility, or, in other words, his or her trustworthiness. By using formal academic language and not talking down to your audience, you can also establish a sense of trust. In addition, it’s important to build a common ground with your audience by seeking goals you have in common with them, regardless of their point-of-view. An authority in a particular field can establish his/her ethos, or credibility, by listing his/her credentials, education, and experience. Depending on their experiences, some students could even be considered experts in particular fields. But usually student writers will have let experts help them create the ethos they need in their argument. By using experts to support your argument, you show your audience your credibility. Therefore, most student writers paraphrase, quote, and interpret the words of experts. This is another reason why research is so important. Emotional Appeals, or pathos A writer can appeal to an audience through empathy, in other words, getting the audience to feel what the writer is feeling. However, emotional appeals usually need logic behind them. If a writer wants readers to pity nineteen-year-olds just because they can’t legally buy beer, his/her older readers won’t feel too much empathy. However, what if the writer describes a young war veteran who has fought for his country, suffered a permanent disability, and almost died, yet can’t even walk into a bar legally and order a beer? Do you think that the writer’s emotional appeal will be more successful? Of course! That’s because there is logic behind the emotional appeal: if somebody is old enough to take on the adult responsibility of serving in the military, he or she should be old enough to drink. Logical Appeals, or logos A writer can appeal to an audience through logic or reasoning. All arguments must be backed up with supporting evidence that is valid and logical. Understanding logical appeals is more complicated than understanding ethical and emotional appeals, yet it is key to writing a good persuasive essay. When you appeal to your audience’s reason, you take them through a process called deductive reasoning. Often, you present them with two truths (or premises), and connect them to create a third truth (conclusion). For example: MAJOR PREMISE: Eighteen-year-olds must carry the burden of adult responsibilities (they are trialed as adults, can be sued, can vote, can get married, can die in the service of their country, etc.) MINOR PREMISE: All men and women old enough to carry the burden of adult responsibilities should be allowed to partake of adult pleasures, such as consuming alcohol. DEDUCTIVE REASONING: Therefore, eighteen-year-olds should be allowed to consume alcohol. For deductive reasoning to work, your audience must believe both major and minor premise. Also, the major premise’s subject or condition must also be part of the minor premise. In addition, successful persuasive papers avoid common fallacies, which are ways of “tricking” people into believing your views. When your audience notices fallacies in your paper, you lose their trust (ethos). Some Common Fallacies: In addition to using effective rhetorical strategies mentioned above, it is important to avoid common logical fallacies to help establish your argument. False Authority – Using an authority with no or unrelated expertise, for example, quoting an angry blogger’s or a celebrity’s views on changing the drinking age. Quoting Out of Context – Misleading your audience by only using part of a quote. Suppressing Evidence – Not presenting obvious evidence that conflicts with your views. Hasty Generalizations – Drawing conclusions from too little evidence. Attacking the Source – Finding flaws in an authority’s views for personal reasons unrelated to the issue discussed. Slippery Slope – Assuming that if one change is made, things will continue on a downward slope, for example, “If we change the drinking age to eighteen, what’s next, sixteen, fifteen?”