PhD Dissertation

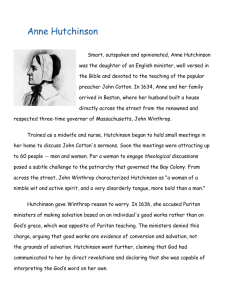

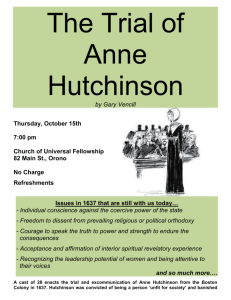

advertisement