WP 106: Technological Capabilities and Samsung Electronics

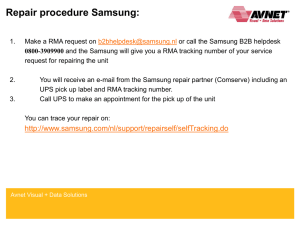

advertisement