2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans

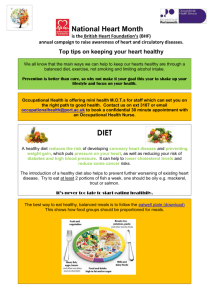

advertisement